Competitive anti-racism

Baddiel's complaint is a dead end.

“Relentlessly irrefutable” said the Times. “Viewers were left in tears,” the Mail announced. “A doc so shocking it sounds like a siren” was the Guardian’s verdict.

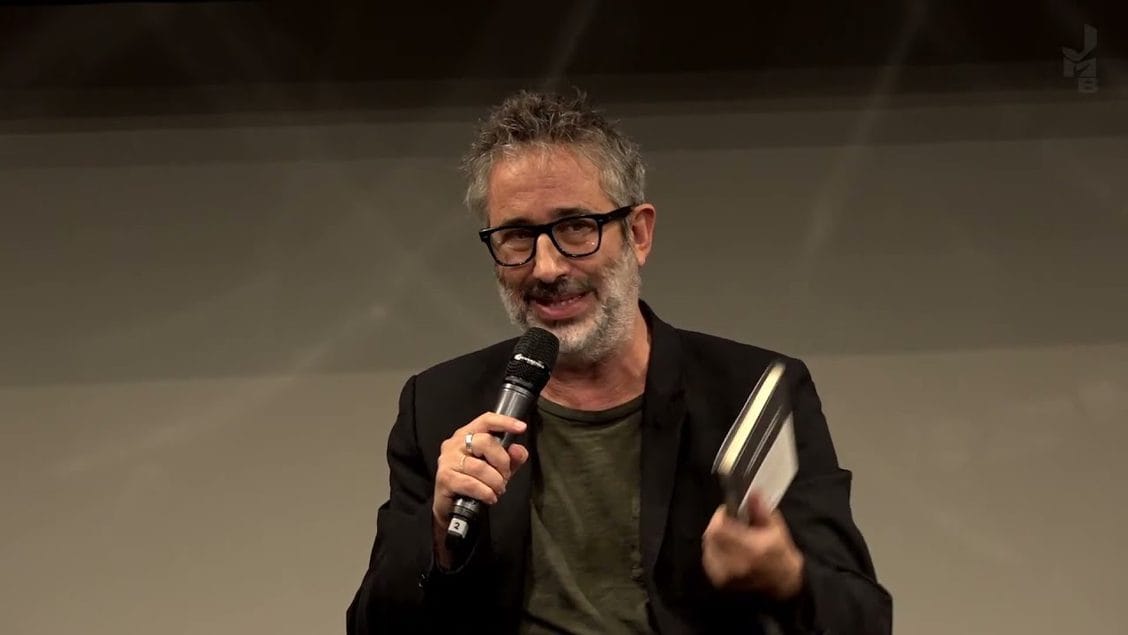

As a glittering stream of reviews rolled in for Jews Don’t Count, cementing its presenter David Baddiel’s place in the pantheon of antisemitism pop scholarship (his book of the same name is already canonical, having been published only last year), I found myself returning to one particular scene in the documentary, which aired on Monday on Channel 4. In it, Baddiel interviews his niece Dionna. Dionna is a Black Jew.

“It’s interesting for me as a biracial person,” she tells her uncle. “I can’t hide the fact that I’m Black; my Dad can hide the fact that he’s Jewish. In America, if my Mom gets stopped by the cops in her car, I’m a little more worried than I am if my Dad [does].”

What follows is a spectacularly awkward exchange. Instead of accepting what his niece is telling him, what she knows from her own experience to be true – that anti-Blackness and antisemitism have very different material consequences in modern-day America – Baddiel refutes Dionna’s implication that Jews like him benefit from racial passing. “Actually,” he tells her, “a lot of Jews had to change their names, in showbiz but also just in life, to get jobs early on. There are whole websites now dedicated to […] unearthing Jews, right? Because the racists think, ‘Yeah, Jews are passing, and we need to stop them passing. Do you see what I’m saying?’” Visibly stunned, Dionna says something about how “hateful” people can be, and the interview ends abruptly. One wonders whether she might have been a little affronted by the comparison.

The scene typifies an understanding of antisemitism that has become increasingly widespread. Its central thesis is that people – progressives in particular – deem antisemitism a “lesser racism”. The idea is commonly expressed in claims that “no other minority would be treated in this way” – or, more catchily, that Jews don’t count. It is an understanding symptomatic of what Arielle Angel describes in Jewish Currents as a “politics of grievance”. Here, the starting point of one’s politics is not wider social injustice but personal injury. This development is rooted, Angel argues, both in a particular Jewish history and in a more widespread “identitarian enshrinement of suffering” that incentivises identity groups to competitively perform their oppression and so to ignore or undermine others’.

It is also demonstrably untrue.

Take the Labour party, supposed ground zero of Jews not counting. Keir Starmer is currently subjecting Britain’s only hijabi MP to a trigger ballot run by friends of her abusive ex-husband, despite warnings from domestic violence charities. Labour staffers described Diane Abbott as “hideous”, “truly repulsive” and “literally mak[ing] me sick”. Rosie Duffield refuses to use trans people’s preferred pronouns. Those who claim negative exceptionalism for Jews on the left betray a striking ignorance of other minorities. In so doing, they breed resentment among those who feel their own marginalisation just as sharply as we do ours. Far from being a useful tool to understand or resist antisemitism, then, the idea that “Jews don’t count” serves only to breed paranoia among Jewish people and resentment among everyone else.

By the logic of “Jews don’t count”, the solution to the perceived hierarchy of racism is to flatten it, resulting in uncomfortable equivalencies. Your Black mother can’t pass to a police officer? Baddiel asks Dionna. Well, I can’t pass to online trolls. “We have experienced something similar,” Baddiel tells Jason Lee, the ex-Premier League player he blacked up to impersonate on his 1990s show Fantasy Football League, “which is being well-known […] and then having an ethnic identity suddenly means that people can use it against you.” Here Baddiel appears to be comparing Lee’s decades of racist abuse on and off the pitch – including by Baddiel himself – with his own experience of once being called a “f****** Jew” at a Chelsea match.

In this understanding, gaining recognition for anti-semitism requires collapsing racism into a set of fungible tokens to be compared and traded on the marketplace of oppression, rather than a complex system of social domination whose effects vary dramatically over time and space. The only way to combat antisemitism, indeed any racism, is to understand it not as some isolated hatred, but to situate it within a matrix of interlocking oppressions whose expressions are different but whose benefactors are largely the same. This work requires, first and foremost, a genuine curiosity about the experiences of others, and the humility to recognise that we may not be unique in our suffering, rather than a knee-jerk attempt to attract attention to ourselves.

In her book on antisemitism, the American columnist Bari Weiss compares antisemitism to a “thought virus,” an “intellectual disease,” an “ancient malady” and “a cancer”. “As such,” writes Judith Butler in her review of the book, “antisemitism seems to exist outside history, recurring in all possible spaces and times.” Similarly, Baddiel speaks of Jewish history as one of continuous “disempowerment”, without acknowledging its clear discontinuities. He remarks on “how frightened Jews remain” after the Holocaust – an empirically observable phenomenon – but provides no analysis of whether this fear remains justified. The result is a documentary that does little to differentiate between people pestering him on Twitter and the siege of a Texas synagogue (a juxtaposition reminiscent of the Scottish-American Jewish writer and Baddiel aficionado Eve Barlow’s description of her online abuse as a “social media pogrom”). When we understand oppression as an unbroken line, we undermine not only others’ experience of it, but our own.

As well as being culturally predisposed to platz (Yiddish for “stress the f*** out”) Jewish sensitivity to threat is actively encouraged by the anti-semitism industrial complex that comprises groups like the Community Security Trust in the UK and the Anti-Defamation League in the US. These hate-monitoring outfits have been accused of using dodgy methodologies that equalise online harassment and violent attacks, and as a consequence churn out misleading research that produces such bizarre claims as that antisemitism is at an “all-time high”. It’s easy to see the political uses of such inflammatory data collection – not least for a state that requires Jews' sense of imperilment to justify occupation, blockade and apartheid.

Ultimately, anti-racism – a task that requires reflection and collaboration – isn't a task best performed by a celebrity, someone rewarded for narcissism. Anti-racism isn’t a forum into which each group sends its mascot to clamour for recognition. It’s a form of politicised empathy generated by listening, by identifying common enemies out of particular experiences. It’s the kind of work done in pubs, not from podiums – and it doesn’t make very good TV.

Rivkah Brown is editor-in-chief of Vashti. This is an edited version of a piece first published by Novara Media, where Rivkah is a reporter and commissioning editor.