The battle of Nelson Street

Vashti reports on a Muslim mayor's fight to save the Jewish East End.

Leon Silver has a hard time saying no to people. Except for rabbi, he has held almost every official and unofficial title at Nelson Street there is: senior warden, honorary treasurer, and Shabbes kiddush-macher, responsible for post-synagogue service receptions (“I always said if anyone could walk in a straight line afterwards, I’ve failed”). When at one of his notorious kiddushim some of the other congregants suggested the shul needed a president, Silver gently bridled: “You can’t have one man doing everything!” He was overruled.

Yet by the time Silver meets me outside the shul gates on a frigid January morning, the ghosts of our grandmothers pinching our cheeks, his honorifics feel as oversized as his winter coat. These days, Leon’s main job at Nelson Street – until recently the last serving purpose-built synagogue in the East End (three others exist, but none were originally synagogues) – is to give tours of the wreckage.

A two-story rectangle wedged between car parks, Nelson Street’s red brick facade and lead-piped windows belong more to a factory than a synagogue. But for the cobalt Star of David above the shul’s entrance, its grimey cornices and demilune windows hinting at something loftier, you’d hardly know it was a synagogue at all. “That was probably deliberate,” Silver tells me, “[so] that it shouldn’t attract attention.”

The 100-year-old shul – East London Central Synagogue, officially – inhabits a corner of the East End that has been happily overlooked by the luxury developers that prowl Tower Hamlets, a borough with more vacant houses than any other in London. Approaching the shul from Aldgate, sleek new-builds collapse into scruffy terraces, juice bars and boutique gyms into caffs and corner shops. It’s as if gentrification called and, like Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the answer came back: “I would prefer not to.”

Silver cracks the heavy chain lock just before his fingers stiffen with cold. Belying its incognito appearance, the shul’s interior is a baroque delight. Famed synagogue architects Lewis Solomon & Son used Corinthian pillars to stake out a compact but sumptuous sanctuary strung together with blues – lapis carpet, powder walls – that Silver, who’s colour-blind, has never seen. He remembers what he saw when he entered the shul three years ago no less vividly, however.

In January 2020, Silver went down to Nelson Street to set up for a Holocaust Memorial Day event only to discover hunks of plasterwork piled before the ark. His first thought was a break-in; they’d had one a few years before. The truth was worse: the roof, which had needed mending for years, had finally begun to collapse. The shul paused services immediately; a couple of months later, lockdown began, and the clocks stopped at Nelson Street.

Today, the shul is a dust-coated time warp: cushions slump in the pews; a kettle filled three years ago teeters on a sideboard; the plasterwork lies where it fell. Fond memories that outside the synagogue were spilling from Silver now pool in his blue eyes. “It’s just sad,” he says, his voice barely a whisper.

Soon after the synagogue closed, the Federation of Synagogues, which owns Nelson Street, assembled its trustees to figure out what to do with the shul. The Fed, as it’s known, had struggled to justify funding Nelson Street for years: the congregation was hanging by a thread, its last full-time rabbi had long since moved on. When the roof first needed fixing over 20 years ago, the Fed had bodged a temporary cover rather than pay for a new one. Now, the building insurance wouldn’t cover the repairs as the roof had been neglected – even the most basic fix would cost £100,000.

If the synagogue was a money pit, the land beneath it was a goldmine: the average sold price of a house in East London has increased 77.4% in just the last decade. The Fed, which had long flirted with downsizing or closing the shul, reached the inevitable conclusion: it would sell the site. Silver wasn’t unused to batting off the Fed, but now they seemed serious. “That was when … I spoke up.”

Incensed that he hadn’t been invited to the council meeting, Silver insisted on attending the next one, and they agreed. There, he delivered an impassioned and entirely improvised speech pleading with the council not to sell the site. He had communal bigwigs and local politicians write to the Fed, urging it to reconsider. After months of negotiation, the Fed agreed it wouldn’t sell Nelson Street, but it wouldn’t continue to bankroll it either. That would be up to the congregants – namely, Silver. They probably didn’t expect that the 74-year-old would accept the challenge – nor that his staunchest ally would be one of the country’s best-known Muslims.

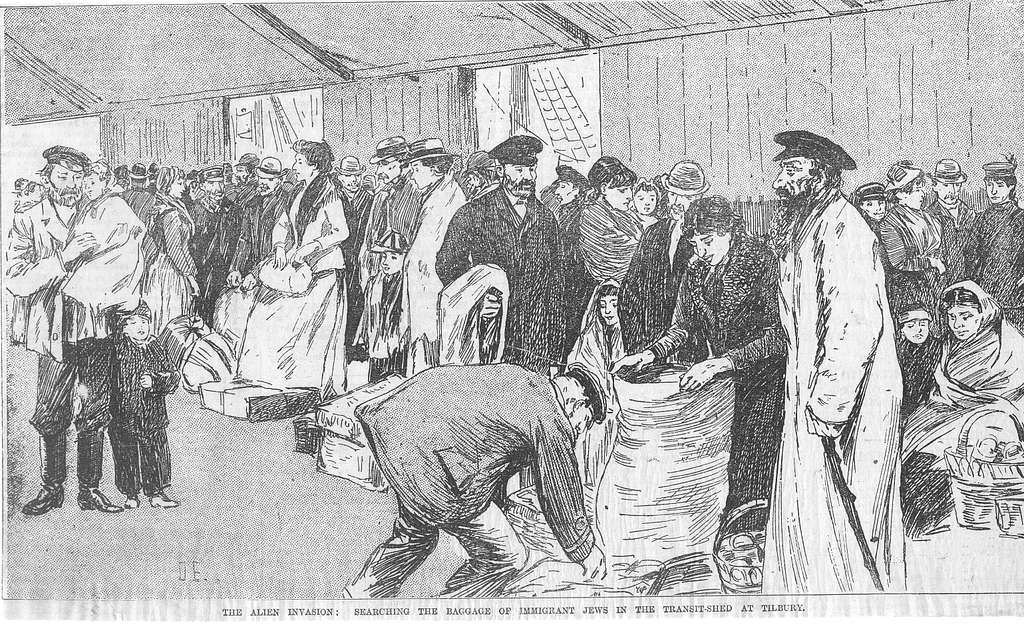

The shtetl transported

Until the mid-20th century, Silver’s story could be any British Jew’s. His paternal grandparents came to the UK from Poland in the 1890s, his maternal grandfather in 1914 from what was then Austria. Silver’s parents, a tailor and a dressmaker, raised him and his older brother on the top floor of a house whose two outdoor toilets they shared with the neighbouring workshop. He bathed in a shissel (washtub) in front of the fire, then once a week at the public baths.

Silver’s parents were married at Nelson Street in 1936; they and the rest of their families joined as members not long after. For this first generation of immigrants, Nelson Street was a surrogate home; a place one could go to eat gefilte fish and chew the fat in the shtetl vernacular. “When Jewish people first came here, they took comfort from being with their compatriots who spoke the same style of Yiddish, the same style of pronunciation, the same style of worship,” Silver told a local journalist in 2012. “It was their security in a strange new world, a self-help society to help with unemployment and funeral expenses.”

The shul stubbornly resisted assimilation: Silver remembers the rabbi delivering his bar mitzvah sermon in Yiddish. Familiar as it may have been, though, recreating shtetl subsistence was not the life most eastern European Jewish immigrants imagined for themselves.

The majority escaped the East End as soon as they could afford to – either further eastward out to Essex, or northward to Golders Green, Finchley and Stanmore, and the hundreds of shuls that had sprouted in the East End withered just as fast as their socially mobile congregants upped sticks. Today, the plaques of some of the more than 20 shuls that merged with Nelson Street over the years lie piled on a landing like headstones. From Silver’s perspective, the story of the Jewish East End is one of steady decline: as a boy, he still remembers the hollowed carcasses of disused synagogues littering street corners.

It’s here, however, that Silver’s story goes off-script: he never left. In fact, he lives on the same square on which he grew up. He still remembers the first non-Jews moving there – nowadays, he’s the only Jew.

Silver stayed partly out of necessity. A retired actor and former “king of commercials” who was once flown out to San Francisco to star in an ad for Kellogg’s Bran Flakes (its jingle – “Tasty, tasty, very, very tasty” – became a popular football chant), “circumstances changed and I ended up being my parents’ carer, and the money gradually disappeared.” He inherited their housing association tenancy after they died, enabling him to resist the push of gentrification despite his own downward social mobility.

Yet there’s also something psychological to Silver’s steadfastness. His parents long gone, his brother now in America, and with no partner or children of his own, the shul is his legacy. “Not having children is my greatest regret,” he tells me. Tending to the synagogue “is leaving something behind.”

Harder to explain is the dedication to the shul of one Lutfur Rahman.

Unlikely allies

In 2008, Rahman and Silver began drawing up a plan to restore the synagogue and its roof in particular with around £250,000 from the Tower Hamlets community faith buildings support scheme plus a comparable amount from English Heritage. The plan was developed over a number of years and was close to delivery in 2015 when, as Rahman puts it, “the tragedy with me happened”.

The tragedy to which Rahman is referring is when he was forced to resign as Labour mayor of Tower Hamlets, and to pay £250,000 towards the court’s costs, after a tribunal found him guilty of corruption in his 2014 election campaign.

It was the year of the Trojan Horse affair and the height of a government-sponsored moral panic about radical Islam; relying on a law last used to suppress Catholic votes in 19th-century Ireland, the prosecution claimed that Rahman had exerted “undue spiritual influence” on Muslim voters.

In his judgement, Richard Mawrey QC wrote: “Whatever may be the position in the rest of London or in the country at large, in Tower Hamlets Muslims in general and Bangladeshis in particular are not in any real sense a ‘minority’ … [a]lthough … Mr Rahman and his associates constantly refer to the Bangladeshi community … as if it were a small beleaguered ethnic minority in a sea of hostile racial prejudice.”

This was not the first time that Rahman’s religion had been used against him: in 2010, a Channel 4 Dispatches programme on Rahman’s supposed links with the Islamic Forum of Europe forced him to resign as Labour leader of Tower Hamlets council. The Labour party later attempted to prevent Rahman from standing as mayor, but failed.

Depending on who you talk to, Rahman is either an Islamist who infiltrated mainstream politics (as a Jewish Chronicle report suggested in 2010) or a spectacularly wronged local politician. His supporters have always contended that the judgement was weighted with Islamophobia; broadcaster and Anglican priest Giles Fraser described it as “steeped in the history and prejudices of English cultural superiority”. Nevertheless, the judgement stuck. The only way Rahman was able to stand for – and win – the mayoralty for a second time in May last year was by leaving Labour to set up a new political party: Aspire. His opponents were, and still are, quick to cite the election tribunal whenever his name hits the headlines.

Just as Silver resisted the tide of Jews exiting the East End en masse, so has he proven impervious to the popular line on Rahman, even as many self-appointed spokespeople of the British Jewish community have enthusiastically espoused it. In 2014, as Rahman’s election campaign got underway – and with it, the press assault against him – Silver was interviewed along with two Christian clerics for an episode of BBC Panorama entitled The Mayor And Our Money, presented by John Ware.

Setting out to investigate Rahman’s mayoralty, Ware – perhaps best-known for presenting a 2019 episode of Panorama entitled Is Labour Antisemitic?, and one the owners of the Jewish Chronicle under whose watch the paper has become notorious for its Islamophobic output – interviewed the three religious leaders in the pews of Nelson Street, including Silver. All vouched for Rahman, but none of their testimonies made the cut. “They knew what they wanted to show,” says Silver.

That isn’t to say he and Rahman haven’t had their differences. When, in 2014, during Israel’s assault on Gaza that the IDF named Operation Protective Edge, Rahman decided to fly the Palestinian flag outside of the town hall, Silver, a liberal Zionist, asked that he fly the Israeli flag alongside it. It’s a disagreement that might have flared into a political firestorm were it not for the fact that Silver and Rahman see each other as more than opposing sides of a geopolitical conflict. Mostly, they are just neighbours: “Whatever is happening in other parts of the world,” says Silver, “we’ve got to live together.”

Now in his second term as mayor and with the shul celebrating its centenary this year, Rahman is determined to finish what he and Silver started. “I’d like to work with Leon and the council and English Heritage,” he tells me, “to see whether we can re-activate the original plan to … preserve this building.”

These plans, drawn up in 2018 by renowned British architect Maxwell Hutchinson, include not only the restoration of the prayer space but its expansion into a museum and library. Silver knows there isn’t enough of a congregation here to justify a prayer space alone (and with Fed rules preventing the shul from being used by the growing number of non-Orthodox Jewish congregations, that’s unlikely to change); Rahman knows how desperate local communities are to learn about the history of the shul. The two men are due to meet with the Fed in the coming months to discuss their plans.

The creation of such a Jewish cultural centre, if it does materialise, would be a great look for Rahman: with the vultures circling once again, and antisemitism still such an effective weapon against the left, it’s possible the mayor wants to insulate himself from criticism. Fatima Rajina, a research fellow at the Stephen Lawrence Research Centre at De Montfort University in Leicester, dismisses the notion that this is a point-scoring mission: “This idea that it’s a fad now to repurpose your Muslim identity and have proximity to the Jewish community is … just not true, historically speaking.” She points out that Rahman’s generation of Bangladeshis, who immigrated to the East End just as Jews were on their way out, “had plenty of interaction with the … Jewish communities who stayed in the East End … they literally work[ed] in the same factories.”

Together in shadow

Nelson Street is an East End anomaly, in that it’s been a synagogue throughout its existence. Most East End places of worship are Russian dolls. In the East London mosque, columns from Fieldgate Street synagogue, which the Fed sold to the mosque in 2015, still stand, preserved out of respect to the site’s history. Around the corner, on the southern wall of the Brick Lane mosque, is a sundial dated 1743, inscribed with the words “Umbra Sumus” – we are shadows. The mosque, it transpires, is an 18th-century former Huguenot chapel, a French Protestant minority that sought refuge in the famously tolerant East End.

We are shadows: a sundial Dad joke? A memento mori? Maybe a nod to the fact that from the silk-weaving French Huguenots to the Irish Catholic dock-workers, Jewish schmatte-traders to Bangladeshi restaurateurs, the East End has been a beacon for those who slip through the city as shadows – “a transit point,” says Rajina, through which the unwashed masses pass en route to the bourgeoisie. It’s a history that the gatekeepers of Anglo-Jewry would rather forget. “For them,” says David Rosenberg, a member of the Jewish Socialist Group whose walking tours of the East End are the stuff of legend, “the East End doesn’t really exist … They just see the East End as the relics of the past who failed to join the middle classes in the northwest London suburbs.”

It’s no surprise, then, that these machers of the Jewish community would let Nelson Street crumble to dust, while a Bangladeshi Muslim mayor who has fought Islamophobes in the courts and on the streets – a man who knows a fellow shadow when he sees one – is intent on saving it. “It’s important to us to have something like this for future generations to understand there was a vibrant [Jewish] community here,” says Rahman. “This was their humble beginning.”

“I’m so sorry, so sorry.” Arriving at Nelson Street, Rahman goes straight to offer Silver a hug. Wrapped in a long black wool coat, the mayor of Tower Hamlets radiates warmth; he’s familiar with everyone he meets, holding their hand in both of his and addressing them as brother or sister. Yet with Silver, it isn’t just some mayoral schtick: the two men go way back. They first met 25 years ago when a local Labour councillor brought Rahman, then Labour leader of Tower Hamlets council, to the synagogue for a visit. Pacing the synagogue now, the colour drains from his face: he’s an observant Muslim and tells me he can’t accept that any place of worship should go to ruin. He’s also got a soft spot for this one in particular.

With its (until recently) affordable housing and proximity to the city’s previously industrial, now financial centre, the East End has been the natural choice for successive waves of migrants; it has also, therefore, been a magnet for the far right. In 1936, Irish and Jewish workers, anarchists and trade unionists joined forces to resist the British Union of Fascists from marching through Cable Street. 75 years later and a few hundred metres away, Silver, Rahman and other local faith leaders got together at Nelson Street to plan their resistance to the Blackshirts’ successors, the English Defence League (EDL).

On the day of the march, counter-protesters would chant the same mantra as their predecessors had at Cable Street: “They shall not pass.” And so they didn’t: the EDL was blocked from marching down Aldgate and its supporters left with their tails between their legs. “These people are so mindless [of] the history of the East End,” says Rahman. Here in the shadows, people stand up for each other.▼

Rivkah Brown is the editor-in-chief of Vashti.

Author

Rivkah Brown is an editor at Novara Media and the former editor-in-chief of Vashti.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.