When the rabbis are anti-Zionists

In the US, a new generation of rabbinical students is shattering the communal consensus.

Despite only emerging in its modern form in the late 19th century, and only gaining widespread support from global Jewry around the 1930s and 40s, Zionism has in recent decades come to be seen as an incontrovertible Jewish value, synonymous for many with the religion itself. Any Jewish person, group or institution that speaks out against it is immediately disparaged as fringe, with influential groups like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) stating unequivocally that anti-Zionism is antisemitism.

Even as that consensus comes under threat from a new generation of diaspora Jews, these organisations have continued to double down. But what happens when the challenge arises from the very rabbis who will lead our communities for decades to come?

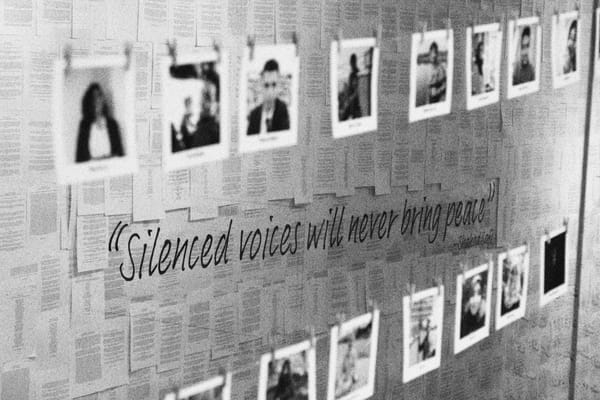

We got a glimpse of these tensions coming to a head in May 2021, when nearly 100 American rabbinical and cantorial students from various denominations signed an open letter to their communities condemning Israel’s latest military assault on Palestinians in Gaza and beyond, and outlining a vision of Judaism rooted in justice and solidarity. “Our tzedakah [charity] money funds a story we wish were true, but perpetuates a reality that is untenable and dangerous,” they wrote. “Our political advocacy too often puts forth a narrative of victimization, but supports violent suppression of human rights and enables apartheid in the Palestinian territories, and the threat of annexation.”

The letter continued: “The current reality, in the streets of a land our tradition deems holy, necessitates a spiritual crisis. A spiritual crisis requires more than prayer. It requires heartbreak, which demands reflection, which then demands action.”

Predictably, the students who signed the letter faced a severe backlash. Several were coerced by potential employers into removing their signatures. One lost a congregation job, and someone else had their employment at a university Hillel terminated. Another felt compelled to remove their signature upon starting a rabbinical internship.

“There is a gap [between the rabbinical schools and the students], and the reaction to the letter really made the gap apparent to me,” said Willemina Davidson, a student at the pluralistic rabbinical school Hebrew College – where 27 out of the roughly 70 students, including Davidson, signed the letter. “There was an email [from the president of Hebrew College] accusing us of not having enough ahavat Yisroel [love of the Jewish people],” they added.

Another of the signatories was Sarah Brammer-Shlay, a co-founder of the American-Jewish anti-occupation group IfNotNow who has since been ordained as a rabbi after completing her studies at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College (RRC). “This is coming from a place of commitment,” she explained. “There is a shift happening. More and more rabbis are saying: ‘We are committed to our Judaism and to embracing Palestinians’ full humanity.’ The backlash [to the letter] shows that it was agitational in a way that felt important.”

Experiencing the reality

“I prefer [to say I support a] ‘one-state solution’ over ‘anti-Zionist’ because people just shut down when you say that, but one way or another, I’m an anti-Zionist,” said S, a student at the Reform rabbinical school Hebrew Union College (HUC), who asked to remain anonymous. S, who had not yet started at HUC when the open letter was written but says he agrees with everything in it, is one of 14 students in his year at the rabbinical school – all of whom are currently based at the school’s Jerusalem campus as part of a mandatory year of study in Israel.

HUC (where 25 former or current students signed the open letter) is not alone in mandating time in Israel for American rabbinical students: RRC has a compulsory summer semester at its Jerusalem campus, while for Hebrew College that period is a full year. The logic tends to be that Israel is a hub of Jewish life and important to many Jews around the world, therefore it is important for rabbis to be able to relate to the place that a lot of their congregants have spent time in or care about. But after seeing the realities on the ground in Israel-Palestine firsthand, many rabbinical students are feeling compelled to speak out.

“The real wake-up moment was when I went to Masafer Yatta,” S explained, referring to a rural area in the occupied West Bank home to a cluster of Palestinian villages that are currently at risk of expulsion, as well as several Israeli settlements and outposts built on their land. The tour was coordinated by Extend, an organisation founded a decade ago to expose Birthrighters to the stories they weren’t shown on their trips, and which has since expanded to provide programming for a wider audience. “I didn’t get what ‘apartheid’ meant until I saw that there’s a nice looking [Jewish] settlement right up this hill, and here the [Palestinian] people don’t have running water because the Israeli government won’t let them.”

According to S, that trip was included in HUC’s programming at the insistence of more senior students, along with a tour of Hebron with Breaking the Silence. S gives the school credit for listening to its students, but HUC seems to be the outlier in this regard. Rabbinical students elsewhere are calling for their schools to provide the same opportunities for critical engagement with the realities of Israel’s occupation and apartheid — and in the meantime they’re pursuing them outside the confines of their institutions.

Willemina Davidson, the Hebrew College student, also joined tours run by Extend and Breaking the Silence during their mandated time in Israel, but of their own accord. “Before coming here, I felt a moral conviction, but I didn’t actually know the specifics,” they said. “And honestly, since coming here, I feel more conviction. It’s been a process of feeling very angry towards various people in my life that have honestly gaslit me about the reality here.”

M, another Hebrew College student who asked to remain anonymous, told a similar story: having already been fairly left-wing in regard to Israel-Palestine before arriving there to study, they reported developing a “much better understanding of the details and how systemic and horrific it all is” from seeing it up close. “In 2023, Zionism is not in line with a lot of the values that we share at Hebrew College,” they added.

“A lot of my disillusionment with Zionism happened while I was in rabbinical school [in the US], and it’s been really special to be here [in Israel-Palestine] in leftist and anti-Zionist communities,” M continued, citing groups like the direct action collective All That’s Left, the yeshiva-based anti-occupation group Ya’aseh Mishpat, and the anti-Zionist minyan (congregation) Boneh Yerushalayim that formed in late 2021. “So much of the narrative that I encountered in high school and college was that anti-Zionists are these self-hating Jews who are fringe and not actually connected to Jewish community. I have dozens of friends who disprove that.”

S, who is also a member of both Boneh Yerushalayim and All That’s Left, no longer sees any reason why his political beliefs should be a barrier to his religious practice. “A lot of young Jews feel they need to check their progressive values at the door when they walk into synagogue, and we need to be part of the change [against this],” he said.

“Often I imagined that I would have to do my religious things with my religious friends who were Zionists, and then do my progressive things in activist spaces, but it doesn’t have to be one or the other,” S continued. “Yesterday, I was weeding a Palestinian’s fields with my friends in the morning, and we were davening together at night. I’m becoming a rabbi and dedicating my life to Judaism. Nobody can call me a self-hating Jew.”

The nearly 100 students who signed the open letter in May 2021 will soon be rabbis and cantors – indeed, some of them already are. In only a few years’ time, the top-down conversation around Israel-Palestine in America’s Jewish communities will likely be unrecognisable from the current state of affairs. For how much longer will the argument that anti-Zionism is antisemitism be able to hold any weight?

The author reached out to HUC and Hebrew College for comment, but neither responded by the time of publication.▼

Sam Stein is a writer and anti-occupation activist based in Jerusalem.