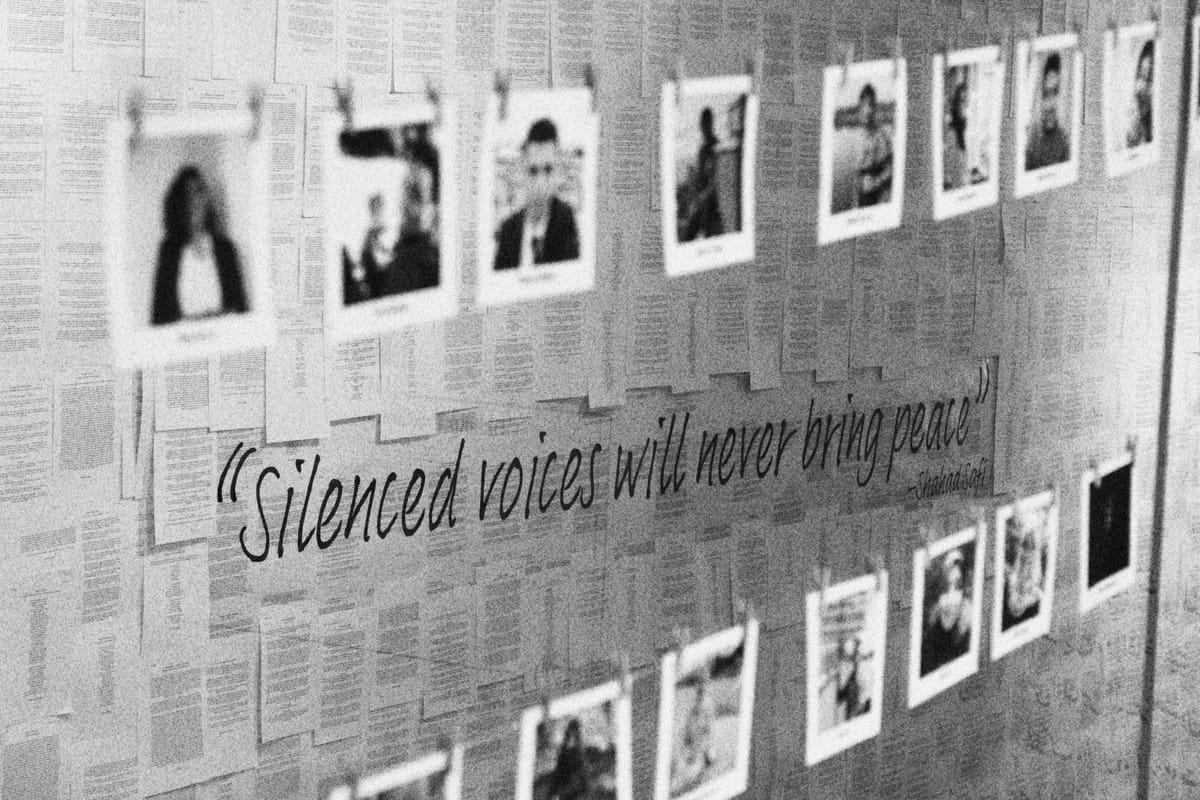

We Are Not Numbers: Refusing Gaza’s dehumanisation

An exhibition reminds us that with every Palestinian life lost, there were mothers who cooked, students who learned and children who swam.

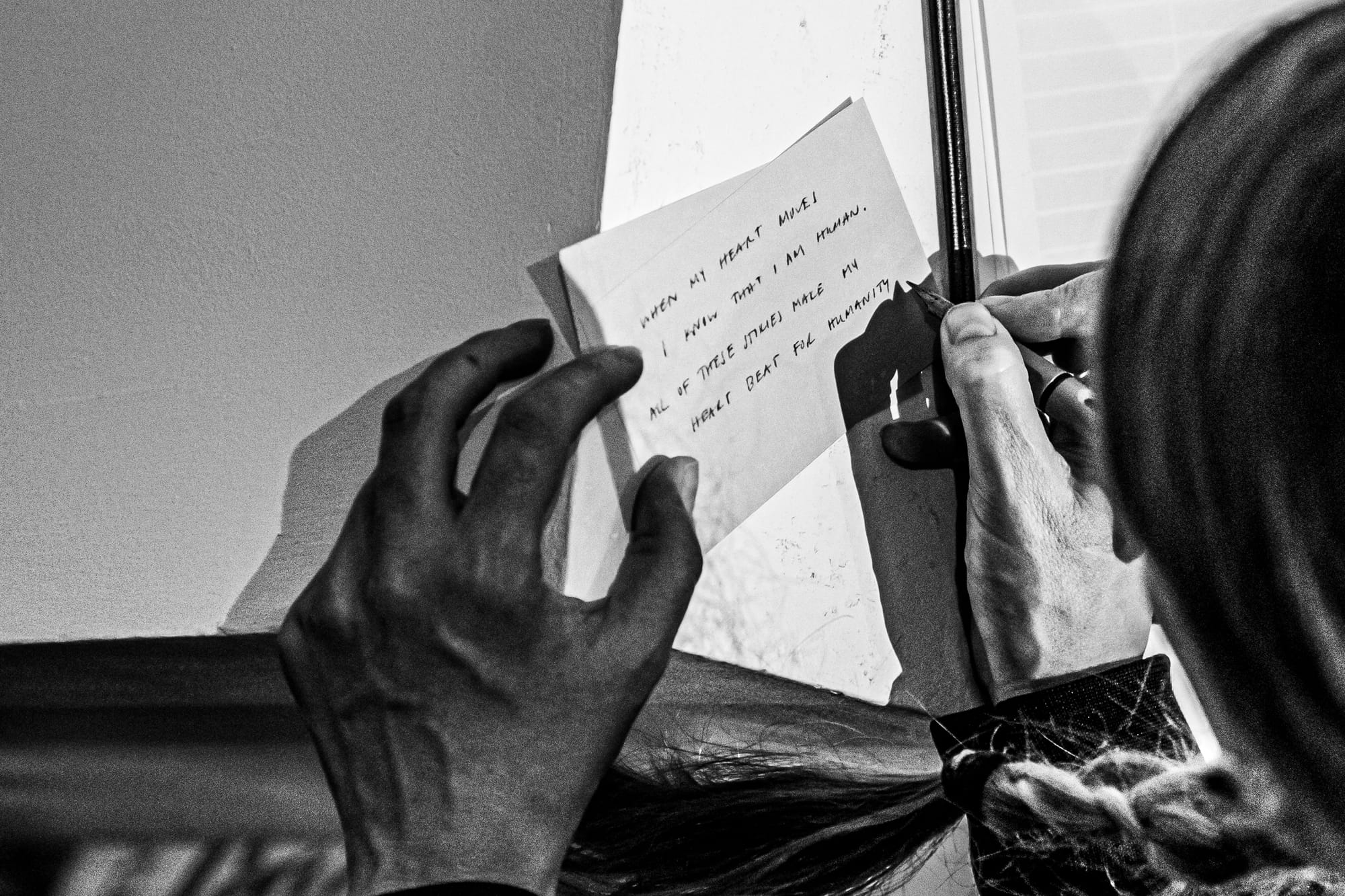

The walls are adorned with words of Palestinians like graffiti on a border. My eyes scan the room before landing on the narration of Leen Abu Said. It’s the first text I read and not what I expect from an exhibition about life in Gaza. “Who doesn’t hate exams?” she opens with blunt honesty. It’s an ordinary question for a student anywhere in the world – I myself contemplated it not long ago. Her frustration transcends region, from one idle student to another, and for a brief moment, I want to believe it could be enough to prove to the world our shared humanity. I nervously read on, however, fearing the moment we are told she could be denied even this.

Curated at P21 Gallery, We Are Not Numbers borrows the name of a community of volunteers working with youth in Gaza and Lebanon since 2015; the network aims to share their stories of grief, laughter, triumph and tears with the world. The exhibition is a reminder of how psychic numbing – the psychological phenomenon that causes indifference to the suffering of large numbers of people – makes the dehumanisation of Palestinians an ordinary practice. Over 220 days of Israeli bombardment, mounting civilian casualties have made this desensitised lens painfully pervasive, with dire implications for the Gazans now relegated to a faceless mass.

Many of the exhibited stories were written before Gaza was reduced to rubble following 7 October. They tell us precisely what wasn’t shown by mainstream reporting during those “before” years: the attachment to normalcy experienced by those living under siege and occupation. Each one is a deeply personal reflection, recalling the rhythm and routine of Gazan life.

After reading Leen’s story, I turn my gaze to Stay Human and Keep your Home Inside by Nedaa Al-Abadlah. Nedaa writes of her struggle to keep her children entertained. Like all children, they grow occasionally restless, so Nedaa asks them to draw things or watch cartoons. Despite the uniquely hostile conditions in which she cares for her family, Nedaa cites the urge to protect them as a testament to the universal spirit of motherhood: ‘‘I feel a kinship with all mothers,” she writes. By recounting her daily struggles with motherhood, Nedaa sees herself as connected to women around the world, urging us to extend the same empathy to all Gazan women.

Hearing her plea, the words of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu painfully emerge in my mind: “We are sons of light, they are sons of darkness.” As Palestinians call for global recognition of their humanity, such language aims to circumscribe it.

In the next story I read, A Love Letter to Gaza by Nada Hammad, another Gazan desperately seeks commonality despite her brutal context, this time by reflecting on her experience of childhood. “I still can see a flower bush pulsing with life”, she writes, “next to the ruins of someone’s home”. She recalls swimming in the sea during summer and the desperate attempts of mothers to soak the sand off their children’s clothes. In her memory, the fine details of Gaza persevere, from the sight of a lone shrub to the texture of tiny rocks on skin.

As minutiae become meaningful, the image next to me juxtaposes – flashes of a ruined home on a television screen, with flattened surfaces obscuring the intricacy of life below. The scene resembles the landscape of Gaza today. It is here that I draw my conclusion about what I’ve read in this exhibition: these short stories, in their illumination of the seemingly micro and mundane, remind us that with every life lost, there were mothers who cooked, students who learned and children who swam. Focusing on the distinct textures, colours and emotions, these memories resist the sweeping characterisation of Gazans as an exclusively “lesser” group; they bring into sharp focus the complexity of Gazan identity, and how it has been rendered imperceptible by genocide.

What does it mean to humanise a people who have been dehumanised? It is a question I often find myself asking as a comfortably British citizen who is the descendant of “alien” Jewish refugees. To scholars like Cynthia G. Franklin, human status depends on the level of belonging to a nation-state, also described as The Right to Have Rights. To protest that a dehumanised group is, in fact, human, is to propose a version of being human that does not yet exist; it demands the creation of a new system that sees people in exile as still deserving of human rights.

Palestinians live outside of these structures that grant such privileges: they have no state nor, increasingly, land. And yet, what we encounter in the exhibition’s stories is not a humanity that ceases to be, but one that endures despite the forces seeking to deny its presence.

We Are Not Numbers gives a face to the victims of a system that forces the word “humanity” to lose its meaning; their voices reanimate what it means to love, fear and hurt amid our broken world. “Stories are a medium of intimacy,” says Mahmoud Zeidan in Voices of the Nakba, reminiscing about his late father’s anecdotes. For decades, the written word in Palestine has been redolent of loved ones who have passed. Tales and elegies have needed to stand in for human touch. An exhibition cannot replace the loss of over 35,000 Palestinians, but it can demand we do not lose what makes us care, cry, and mourn. A world without this dehumanises us all. ▼

This exhibition ran at P21 Gallery between 3–11 May. You can learn more about We Are Not Numbers’ upcoming projects and stay up to date with their work here.

Alexandra Diamond-Rivlin is an artist, writer and editor at Vashti.