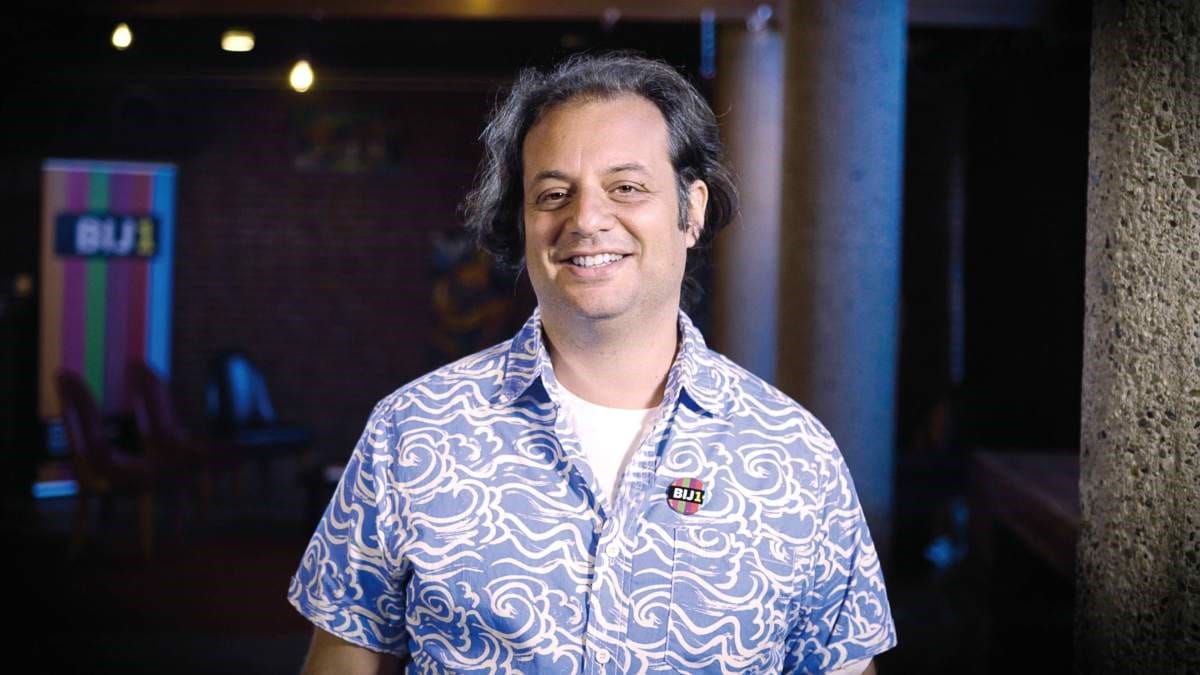

Meet Yuval Gal, the anti-Zionist Israeli running in the Dutch elections

Gal left Israel aged thirty, appalled by the country’s trajectory. Now he’s continuing the fight against injustice from the Netherlands.

The best thing about living in The Hague,” says Yuval Gal in soft-toned but thickly-accented English, “is that I’ll have a front-row seat when Benjamin Netanyahu is tried at the ICC [International Criminal Court].”

Gal joins me on Zoom in the middle of an election campaign, though you wouldn’t know it from his relaxed demeanour. Elections to the Netherlands’ House of Representatives are scheduled for 17 March and Gal is competing for a seat – despite having only become a Dutch citizen three years ago. More surprising still is the fact that he is running for a party that supports boycotting the country of his birth.

Gal explains that his political journey was informed by his experience growing up in Hod Hasharon, a satellite town of Tel Aviv. As a child he remembers walking with his Dad, asking him about the provenance of various buildings. “He would just shrug and make up some story. Eventually, I came to understand that it must have been someone’s house, but that they were no longer there.”

Curiosity about how the State of Israel came into being gradually calcified into an assured anti-Zionist politics, says Gal. His mandatory service in the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) – he chauffeured for a brigadier general – exposed him to the iniquity not only of the occupation, but to those that plagued army life where, he claims, sexual harassment and class-based discrimination were routine. Gal’s brother managed to excuse himself from serving in the IDF; a number of friends went to prison as conscientious objectors. He regrets not doing the same. Still, he remembers feeling fleetingly hopeful about Israel’s future during this period. “Those of us on the hard left had criticised the Oslo Accords but were still cautiously optimistic about the prospects for peace. When the Second Intifada broke out towards the end of my military service, we lost all hope.”

By the time he was 30 and with a child of his own, Gal decided to up sticks. “I was learning video editing at the time when I had this crystallising moment. I was watching a film of some children playing with tanks for Israel’s Independence Day. It suddenly hit me: this isn’t normal, this isn’t the future I want my son to have. I don’t want him to have to serve in the army – I don’t want him to learn to hate.” Gal opted for the Netherlands in part because his child’s mother had lived there, but also because they assumed it would be a more tolerant and equitable society in which to raise a child.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K5adyVnNE40

Yet life as a middle-class Ashkenazi Jewish man in Israel affords certain privileges, privileges that were brought sharply into focus for Gal when he suddenly became an immigrant abroad. His first flat in The Hague was in a working-class neighbourhood which, along with his middle-eastern accent, led some locals to suspect him of being a drug dealer. Things hardly improved when he moved to a more affluent area: Gal recalls being stopped by the police on his way to work at least twice. “I asked them why they were stopping me; they said I looked dirty.”

Gal credits his understanding of how racism and economic exploitation reinforce one another to this experience; or as the cultural theorist Stuart Hall might say, the prejudice Gal faced enabled him to see that race and identity are the modalities through which class is lived. “I already had a Marxist political analysis, so I understood that I would face racism, but I was definitely naive about the extent of it in Dutch society,” he tells me. Armed with this fresh perspective, Gal sought a political home that coupled a leftist economic programme with an explicit commitment to fighting racism. He found one in BIJ1.

BIJ1’s founder, the Surinamese-born Sylvana Simons, was already well-known in the Netherlands before she formally entered politics in 2016. A former presenter for Dutch MTV, Simons received a deluge of racist abuse after appearing on a current affairs show in 2015 to condemn the Dutch tradition of dressing up in blackface as Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), a character associated with the Dutch festival of Sinterklaas. Gal remembers this period vividly. “The way the all-white panel looked at her, the assumption was: you’re a violent, ungrateful, aggressive person because you’re a black woman. And you have the audacity to criticise our culture?”

Following the TV row, Simons entered the political fray, first joining the pro-immigration party Denk (Think) but leaving soon after she concluded that the party’s leadership was more interested in exploiting the media attention she attracted than in ensuring her physical safety. That same year, she launched BIJ1; pronounced Bye-en, meaning “together” in Dutch.

The party has quickly become a pole of antiracism in the Netherlands, where the far right is on the march. Earlier this month, the Dutch parliament voted overwhelmingly in favour of surveilling Mosques for “foreign influence” and withdrawing state funding from Muslim organisations and institutions accused of “problematic behaviour”. Only Denk voted against the legislation (BIJ1 currently has no representation in parliament).

Meanwhile January saw an eruption of riots across the country in response to the imposition of curfews to curb the Covid-19 pandemic. Many were simply protesting the restrictions; others had more sinister motivations: “While some were the same people calling for the deportation, criminalisation and even death of Muslims, racialised communities and migrants,” writes former president of the National Union of Students Malia Bouattia, “they were also triggered by any hint that their own freedoms could be limited.” With politicians from across the political spectrum competing to appease this swelling xenophobia, the need for BIJ1’s unapologetic antiracism has grown.

With its coalition-oriented electoral system, Dutch politics is already home to an alphabet soup of left-leaning parties, including the Socialist Party, Groen Links (Green Left) and the Pvda (Labour Party); though none have managed to usurp prime minister Mark Rutte’s right-wing VVD (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy), the largest party in government since 2010.

What sets BIJ1 apart from its left-wing cousins is its refusal to see antiracism as a side issue, coupled with its radical commitment to upending the status quo. In a recent interview with openDemocracy, Simons said: “We’re not advocating making this system better or fairer. That’s not gonna happen! We’re advocating system change.” Like other progressive parties, they recognise representation as part of this change: BIJ1’s candidate list has non-white majority and includes an autistic Muslim woman, Nihâl Esma Altmiş, as well as transgender activist Petra Kramer, whom Gal considers a political mentor. Yet this is not where BIJ1’s programme ends. The party’s manifesto calls for an end to ethnic profiling; a 30-hour working week; the abolition of tuition fees; and the replacement of GDP with “gross national happiness” as the primary economic indicator. Such policies are the product of careful deliberation between those at the sharpest end of racism and inequality, says Gal: “We are the party of the people who are always ‘the problem’, but now we’re speaking for ourselves.”

In line with its commitment to decolonisation at home and abroad, BIJ1 supports the Palestinian right of return, endorsing a one-state solution with full civil and political rights for all people in Israel-Palestine. BIJ1’s solidarity with Palestinians – evidenced also by its rejection of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Working Definition of Antisemitism, on the grounds that it conflates antisemitism with anti-Zionism – has provoked allegations of antisemitism against the party. In 2019, the editor of the Netherlands main Jewish magazine Nieuw Israëlietisch Weekblad announced that she was emigrating to Israel because of rising antisemitism, naming Denk and BIJ1 as the key culprits, in what turned out to be a poorly conceived Purim prank.

For his part, Gal interprets BIJ1’s pro-BDS stance as evidence not only of its meaningful solidarity with Palestinians, but of its refusal to erase anti-or non-Zionist Jews, as left-wing parties are wont to do. “Support for BDS is what convinced me that BIJ1 are actually interested in talking with people, not just about them, even if it’s politically inconvenient,” he says.

BIJ1 is by no means the first party to be subjected to a double standard on antisemitism, Gal is acutely aware of how Jewish concerns are routinely deployed to derail left-wing projects. “A lot of people were closely following what was happening with Corbyn and the antisemitism debacle. It was both fascinating and depressing to see that this strategy actually worked,” he notes.

In Gal’s view, this coordinated effort to indict pro-Palestinian parties has resulted in the Netherlands’ most pernicious antisemites escaping scrutiny. “There is a party leader in the Netherlands, Thierry Baudet, who spoke at a far-right event where Flemish volunteers for the SS were allegedly commemorated; has been pictured with a copy of Mein Kampf; and has reportedly blamed George Soros for coronavirus. And yet pro-Israel groups invited him to attend their antisemitism demonstration, effectively giving him a hechsher (Kosher seal of approval).” As with nationalist politicians the world over, Baudet, who leads the far-right party Forum for Democracy, uses his staunch support for Israel as a shield against charges of antisemitism. This did not prevent his resignation after it emerged that he had attempted to block the automatic expulsion of party members accused of sharing pro-Nazi messages over WhatsApp; it may, however, have helped him make the case for his reinstatement just one month later.

Antisemitism is likely to be less electorally significant for BIJ1 than it was for Labour, since the party is not yet viewed as an electoral threat by those who might wish to weaponise the issue. Absent a socialist revolution between now and 17 March, BIJ1 will remain marginal in Dutch politics, though along with other new anti-racist parties, it is likely to continue gaining ground; but Gal is optimistic the party will pick up at least a couple of seats. He is less confident about his own prospects. Members of the Dutch House of Representatives are elected using a party-list proportional representation system and since Gal is placed 11th on the BIJ1 slate, his chances of winning office are exceedingly slim.

This fact doesn’t seem to weigh down a buoyant Gal, whose campaign at this stage is more about making a political statement than becoming a politician. “I hoped to use my candidacy to discuss how antisemitism is being weaponised against the left and to loosen the hold that Israel seems to have on Jewish identity in the diaspora. Regardless of what happens in the election, I want to continue building BIJ1 as a site of struggle for oppressed people, and giving voice to the Jewish left in the Netherlands.” He says he has plans for a radical beit midrash (Jewish study group) – because that’s where all the best revolutions are hatched. ▼

Aron Keller is an editor for Vashti.

Author

Aron Keller is an editor at Vashti.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.