‘Yiddish has always been anarchistic’

Punks and Yiddishists in Tel Aviv unite.

“BOKER TOV!” (“GOOD MORNING!”) shouts the guitarist with the spiky green hair. “BOKER TOOOV!” the 100-strong crowd shouts back. It’s a Thursday evening in late November, and YUNG YiDiSH is packed full of punks. The ages range from preteen to prehistoric, but everyone looks right at home and dressed for the occasion: mohawks, dreadlocks, leather jackets, fishnet tights, walloping great big boots. One man whose face is mostly piercings wears a t-shirt that says “FCK TLV”.

The punks inside YUNG YiDiSH can be as loud as they want, because the library is on the fifth floor of Tel Aviv’s central bus station. Most Tel Avivians consider the station an eyesore, a giant stain on the landscape of the city (which is hardly famed for its architectural charm) and a magnet for criminals and crackheads. But that view is superficial.

When Ran Karmi designed the bus station in 1967, he envisioned a city under one roof. He imagined streets lined with clothes shops and cafes, and plazas where people could sit and eat. The blueprints were hailed an architectural triumph, but a range of demands from the bus companies, local council and investors scuppered those grand plans. After all the tweaks and changes, it came out rather odd.

The station – the largest in the world when it opened, and now second only to Delhi – was built bang in the middle of the neglected residential neighbourhood of Neve Sha’anan, so by the time it was completed three decades later, anyone who could afford to had moved away, leaving behind those with no other choice. And while many Tel Avivians were excited by the shiny new station, enthusiasm soon faltered. Shops shuttered, rents dropped and that’s when the station became a second home to some of Tel Aviv’s most marginalised communities – African asylum seekers and south-east Asian migrant workers in particular – and subculture began to flourish.

The station plays host to a weekly Filipino food market, a dance school, a clinic that offers sex workers free healthcare, and a money-wire service for foreign workers to send home remittances. Wander around for long enough and you’ll also find a synagogue, a couple of churches, a sealed-off bus tunnel that is now home to a colony of Egyptian fruit bats, an abandoned cinema, the recently shuttered nightclub The Block, more clothes shops than you can count, and an underground nuclear bomb shelter with room for tens of thousands to take cover.

Structurally, this place is designed to confuse: you enter on the fourth of eight storeys; the signage makes no sense (some floors have an “A” area and a “B” area that are discontiguous); and floors and staircases slope up and down at strange angles. No one has ever found their bus platform in under 10 minutes (fact) and it’s equally difficult to find YUNG YiDiSH – except when they’re hosting a punk show, which you hear before you see.

The punks aren’t the only people who call this place home. YUNG YiDiSH hosts weekly Yiddish classes, art exhibitions, public lectures, queer parties, zine fests, cabarets, theatre performances, educational tours, poetry readings, and drag performances. Every Sunday it hosts a rotating line-up of Klezmer bands, serving kugel and gefilte fish to the audience during the break.

Tonight, there are people crashing around in a discarded wheelchair, and I witness a fight break out over a skateboard; a girl with pink hair grabs it, lies down on her stomach, and her mate rolls her into a shop window like a bowling ball. Inside, a mosh pit has formed. Kids crowd surf on rotation: a conveyor belt of Doc Martens and mohawks. One girl drags a rocking horse (a permanent fixture in YUNG YiDiSH for reasons nobody quite understands) onto the stage and sits there happily drinking a can of beer while the band thrash about around her.

“Afterparty at Teder?” the singer yells to a braying crowd. The suggestion is tongue-in-cheek: while Teder is a lively cultural complex not far from the centre of Tel Aviv and the obvious go-to weekend spot for the young and hip, YUNG YiDiSH is a place for misfits, and in Tel Aviv that’s rare. Rent is extortionate, and most underground venues have been bulldozed to make room for apartment blocks, so it’s easy to assume all subculture has been squeezed out. But it exists, and YUNG YiDiSH is one of the few places you can find it.

Finding a home

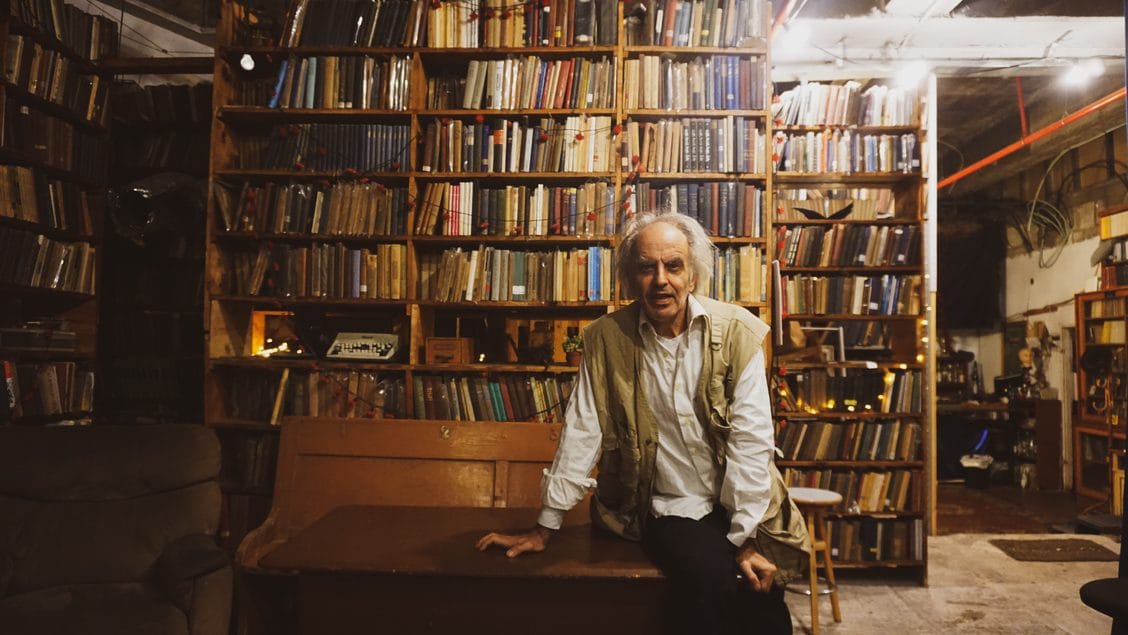

A few days later, with the church window outside boarded up and the wheelchair thrown into recycling, I catch up with Mendy Cahan, the founder of YUNG YiDiSH. He looks, quite frankly, like he’s recently been electrocuted — not just because all his hair stands on end, but because of the look in his eyes. They’re alight with creativity.

“Shouldn’t all culture be open to everyone?” he asks, sitting on a chair with his legs crossed in the exact spot the crowd of punks was moshing. “Shouldn’t culture be affordable to everyone? Shouldn’t it be totally inclusive? What we do here should be normal. Paying 300 shekels [around £70] to get into a venue is not.”

Cahan was born in Belgium in the mid-60s, a couple of years after his parents, who survived the Holocaust, had relocated there from Romania. “I grew up in Belgium, which is a small country but it’s in the middle [of Europe] so it absorbs everything,” he tells me. At home he spoke Yiddish, but he soaked up the country’s many languages like a sponge, and dug for books in his spare time. He loved to go to his local library and find an old forgotten newspaper in the middle of some dusty encyclopaedia. “Looking for these things became my interest,” he says.

By the time he was in his late teens he spoke German, Flemish, English, Dutch and Yiddish. He moved to Israel in the 1980s to break out of Antwerp’s small, Orthodox community without antagonising those he left behind. “I enabled a dramatic change without big drama,” Cahan muses, “which is also reflected here in this library.”

Cahan’s fascination with Yiddish coincided with his gentle exit from Orthodoxy. Yiddish was a way to stay connected to his eastern European roots, and he loved its sense of anarchy and ability to survive against all odds. A mixture of Hebrew, Aramaic and high German, Yiddish originated among Jews in ninth-century central Europe. It’s a supple language, malleable, like a ball of clay. Squeeze it and it’ll seep through your fingers, finding a way to exist in a different shape to before.

Cahan studied philosophy and literature when he moved to Israel in his early 20s, and was surprised to discover that once the world’s great literature had been translated into Yiddish, it took on a life of its own. So when he began delivering daily news and providing Yiddish prayer services on Israel’s public radio station, Kol Yisrael, he took the opportunity to appeal for donations of Yiddish newspapers, books and magazines. And so it began.

In 1992, he set up Yiddish stalls at book fairs, and then joined forces with NGOs and cultural spaces. The books found their first permanent home in Jerusalem in 1993, and expanded into Tel Aviv in 2006. The library is in the bus station because that was the cheapest place Cahan could find. The space was completely empty when he found it, with birds nesting in the rafters, but all Cahan could see was potential and a place to store and showcase the four tonnes of Yiddish books he’d collected over the years.

“It was obvious to me that a cultural place, in order to be relevant, needs to be in a noisy space, a hurtful space, a space where you can do things,” he explains. As if to demonstrate his point, a bus rumbles overhead and the entire place shakes.

On the margins

Scores of volunteers find their way to YUNG YiDiSH, attracted by the free-flowing, outsider mentality. Some are ex-Hasidim, some queer and trans folks, and some simply want to connect with their roots – but all are seeking community. “I didn’t build a structure for volunteers,” Cahan explains. “In the beginning, someone just took a cup and washed it, and then someone else helped them with the rest, so the concept of volunteering invented itself. Many of them are on a quest, and it'll take them years. But this place is saying: take your time. Because culture takes time.”

Yiddish language and culture, Cahan explains, has always thrived on the margins. “There is no establishment behind Yiddish,” he says. “We don’t have an Académie Française, we don’t have powers from above. But Yiddish finds its way, and we manage, and have always managed, to teach our children to read and write without these structures.”

Most of the world’s Yiddish speakers were murdered during the Holocaust, and those that survived found themselves condensing the language, speaking in whispers and abbreviations to reduce their visibility. Those who found their way to the nascent state of Israel were compelled to stop speaking Yiddish in favour of Hebrew – which symbolised the “new Jew” in Zionist ideology – just as those arriving from the Middle East and North Africa were forced to shed their Arabic language and identity.

So YUNG YiDiSH represents a form of resistance in many ways, not least because a space for Yiddish culture – in the centre of the “first Hebrew city,” no less – is a space for all marginalised culture. “Yiddish has always been anarchistic,” Cahan says. “It always finds its way and it always slips out. You cannot contain it. I just give it a voice, a space, to be expressed.”

Despite his achievements, Cahan doesn't take too much credit for what he created here. He sees the Yiddish language and culture as a living, breathing organism; all he did was find a place to preserve Yiddish books, and the culture happily followed.

And you wouldn’t think a library that preserves an endangered culture is a good place to throw wild parties, but the books stay protected, despite lining the stage and the main floor. “I think there’s a conversation going on between the books and the punks,” Cahan says. “They respect each other. There’s a give and take. Did you see the place afterwards? After all that moshing and dancing, not a single book was out of place.”▼

Alice Austin is a freelance journalist covering culture, subculture, and the intersection of politics and music.