Sanctuary in the sewers

How one family survived the Lviv ghetto, with the help of a Catholic sewer worker and occasional burglar who knew the underground labyrinth like the back of his hand.

On Friday morning, Lviv awoke to news of a Russian assault on its airport, rupturing the illusion of peace in a city that has become a relative haven in a country engulfed in the flames of war.

Lviv was established in the mid-13th century as a royal principality and thrived for centuries as a cultural and economic hub. Situated just 50 miles from the Polish border and at the Western fringes of the former Soviet Union, the city has had many names, including Lemberg, Lwów, Lvov, Lviv and Leopolis – the city of lions. It was Polish for a long part of its history, but today the Unesco world heritage site is the largest city in western Ukraine and a bastion of Ukrainian nationalism.

I have never been to Lviv but the city looms large in my family’s history. It was the birthplace of my grandfather, Matis Keller, and the setting of his niece’s own extraordinary story of survival.

My grandfather was born in 1911, when the city was officially known as Lemberg but was often referred to as Lvov. Pre-war, Lvov was a global centre of Jewish culture and religion, home to the world’s first Yiddish-language daily newspaper. By 1939, Lvov’s Jewish population had doubled to around 200,000 due to an influx of Jews fleeing Nazi-occupied Poland.

When the Nazis invaded in 1941, Matis fled east to join the Russian army before deserting to join General Anders’ Polish army, like many Jewish soldiers. Matis’s eight siblings and their families all perished in the Holocaust. The only other survivor in his family was his niece, Klara.

Klara Keller was my father’s first cousin, the daughter of my grandfather’s brother. At 17, she found herself imprisoned in the Lvov ghetto, having already witnessed her mother’s execution. Her father and brother had been deported to the nearby Janowska concentration camp, leaving Klara and younger sister Manya to fend for themselves.

In darkness

In the flat next door to Klara and Manya, a small group of men who feared the ghetto would soon be liquidated were busy hatching an audacious escape plan. Using knives, forks and any other makeshift tools, they spent painstaking days and weeks digging out a narrow shaft from the flat directly into the sewers below.

A black-marketeer by the name of Mundek Margulies was an indispensable member of this digging expedition. Raised in a Polish orphanage, Mundek was remarkably resourceful, and had quickly developed a reputation in the ghetto for being able to get hold of almost any commodity (he was repeatedly marked down for deportation to the death camps, but managed to remain in the ghetto by producing false papers).

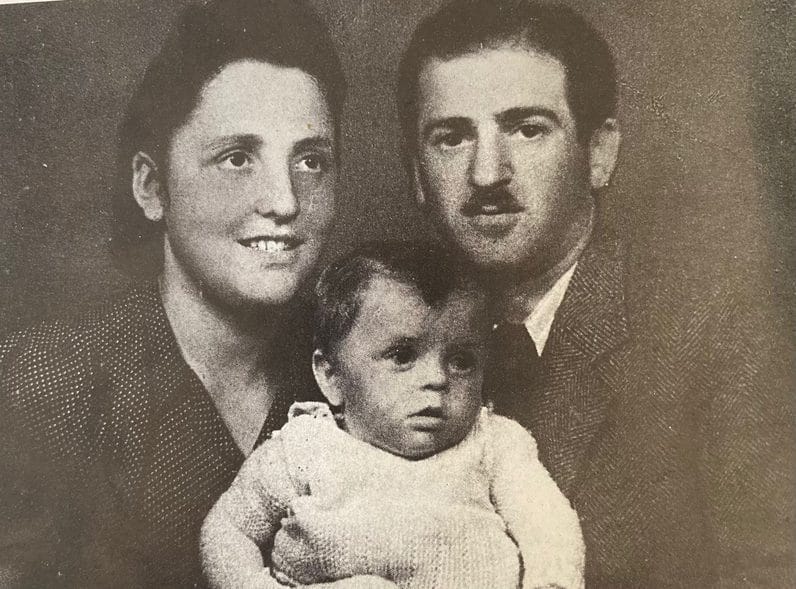

While working on the escape route Mundek met Klara and immediately took an interest in her welfare, delivering her food and medicine. As Klara would later tell Robert Marshall, the author who would turn her experiences into the book In the Sewers of Lvov (1990): “I can’t remember how we survived, my sister and I, before Mundek came along. We had no money, Manya had no work and was getting sick – and then he was there, wheeling and dealing.”

In June 1943, the escape planners sprang into action as SS guards – helped by members of the Ukranian People’s Militia – raided and destroyed the Lvov ghetto, murdering thousands of Jews and deporting the survivors to death camps. On that terrible day, Klara and Mundek joined dozens of other desperate Jews in climbing down the narrow shaft into the foul-smelling Lvov sewers, where they planned to wait out the war.

The descent into the sewers was particularly harrowing for Klara. Manya was meant to join them but amidst the chaos and hysteria, decided she couldn’t face the conditions and refused to go. Klara recalled being caught in a tug of war between Mundek and her sister at the shaft’s entrance: “He was pulling me one way and she was pulling the other.” Mundek eventually won out, but Klara would become consumed with guilt for leaving her sister behind.

Hundreds of Jews escaped down into the sewers. Many drowned in the rushing waters below, while others who could not tolerate the conditions fled the dark, rat-infested tunnels only to be shot by SS guards as they exited; some took their own lives out of desperation.

Enter Leopold Socha

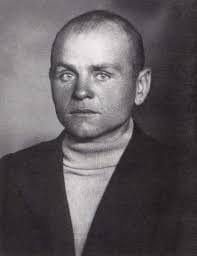

Mundek and Klara would likely have suffered the same fate had their group not managed to solicit the help of a Polish sewer worker. Leopold Socha’s unrivalled knowledge of the underground labyrinth allowed him to throw patrolling German soldiers off the scent. A devout Catholic and part-time burglar, Socha initially agreed to provide a small group of Jews with food in exchange for money.

Over time he became emotionally invested in their plight and continued delivering essential supplies when the cash ran out. Along with food, Socha brought the fugitives snippets of news from above ground, and took their ragged clothes home to be washed each week. On Pesach, Socha gave the group potatoes in place of bread; when Stalingrad fell, Socha turned up with vodka to celebrate.

Still, conditions in the sewers remained unimaginably hellish. Having been driven to the brink of sanity, some members of Mundek and Klara’s group chose to leave – they were later found dead with bullet wounds at the sewers’ entrance. One woman gave birth inside the sewers but chose to smother the baby to death, fearing its cries would alert the Germans to their presence.

During those dark, dreadful months, Mundek distinguished himself through acts of bravery, often undertaking dangerous missions above ground in search of supplies that might make life in the sewers more bearable. On one such excursion, he was spotted by a Ukrainian guard and avoided being shot only by bludgeoning the man to death with a hammer.

As time wore on, Klara became increasingly desperate for news about her sister, having learnt that Manya had been taken to the nearby Janowska concentration camp. In an astonishing display of courage and ingenuity, Mundek smuggled himself into the camp by swapping identities with an inmate he’d befriended. After a day or so in the Janowska camp, Mundek made contact with Manya and once again implored her to join them in the sewers. Manya refused once more but left Mundek with a letter for Klara, insisting she was not responsible for her fate. It would be the last time Klara heard from her sister.

Liberation, Soviet occupation

On 27 July 1944, Socha lifted a manhole cover and loudly informed the subterranean captives that they were finally free. As the survivors tentatively emerged from the darkness into the blinding light of day, they found a city under the control of the Red Army. After 14 months in the sewers, the group of twenty Jews helped by Socha had dwindled to 10.

About a year after the liberation, Leopold Socha was killed after colliding with a Soviet military truck while out cycling with his daughter; his last act was to steer his daughter’s bicycle out of the truck's path. The Jews rescued by Socha reunited at his funeral where they overheard someone say of his death, “This is God’s punishment for helping the Jews”.

Lvov to London

Mundek and Klara married in Lvov then moved to London. They settled in Stamford Hill and established a flourishing catering business, owned until recently by their children and which catered my own bar mitzvah. Mundek and Klara passed away in 1997 within six months of each other. Their story was turned into the Oscar-nominated film, In Darkness, based on In the Sewers of Lvov.

As Lviv swells to capacity once again, with millions of internally displaced Ukrainians seeking shelter from Russian bombing in the east, it is tempting – even convenient – to look for echoes of the past. The war in Ukraine has prompted the largest migration of Europeans since my grandfather fled Lviv for Russia when the Nazis invaded, albeit this time going west not east. When Putin propagandises about “denazifiying” Ukraine, he invokes the Holocaust as a pretext for waging a flagrant war of aggression.

Yet reaching for historical parallels to explain our present reality can also lend itself to fatalism, in which history is witnessed as an unceasing cycle of despair that consumes the countervailing heroism of the world’s Leopold Sochas. While the UK government’s shamefully inadequate refugee resettlement scheme may be true to form, the public enthusiasm for Homes for Ukraine – to which almost 150,000 individuals and organisations have applied – defies the violent nativism that often prevails in British politics.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes,” Mark Twain supposedly said. One month before the invasion of Ukraine, my sister gave birth to a daughter: Clara.

Aron Keller is an editor at Vashti.