How Britain paved the way for a century of Zionist colonialism

"While British support for Zionism is often framed around claims about Jewish safety, the reality is that Britain supported the Zionist movement and issued the Balfour Declaration for its own imperialist aims."

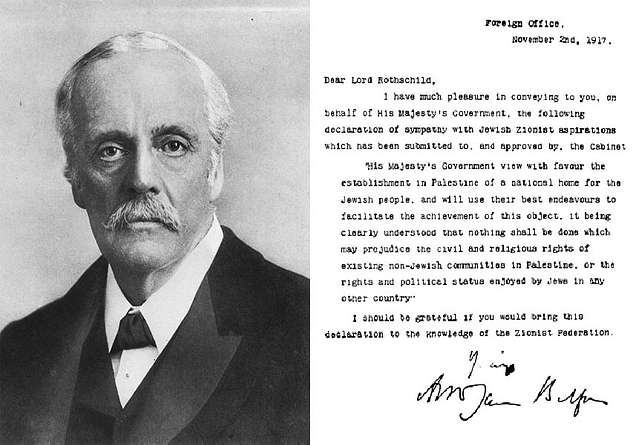

On 2 November 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour presented a 67-word letter to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leading advocate for the Zionist movement in Britain. It read: “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” and “will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.” This letter became known as the Balfour Declaration.

Over a century after its publication, successive British governments and supporters of Israel alike have celebrated Balfour’s letter, portraying it as a noble act which led to the establishment of the world’s only Jewish state.

However, a closer look into this century-old pledge and its legacies today shows that there is little to be proud of. Balfour’s declaration gave the Zionist movement imperial backing to colonise Palestine, thus setting in motion the mass ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, culminating in both the 1948 Nakba and the establishment of the State of Israel.

While British support for Zionism is often framed around claims about Jewish safety, the reality is that Britain supported the Zionist movement and issued the Balfour Declaration for its own imperialist aims. In fact, the leading members of the UK’s wartime cabinet were antisemitic and cared little for the fate of Europe’s Jews. This dynamic continues today, as the Palestinian liberation struggle and its supporters - including Jewish people - are smeared as antisemites by Israel and its allies, all while many of those same allies indulge in antisemitism themselves.

Theodore Herzl, the founder of Zionism, once wrote that “the anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” Beginning with Balfour and the British Empire over a century ago, Herzl’s prediction has continued to hold true. What this friendship masks is that white supremacy and Zionism, from Balfour’s time until today, complement and very much rely on one another to achieve their aims.

Imperial Roots

In 1917, the British found a confluence between their geopolitical interests and those of Zionism. In turn, the Zionist movement found in Britain an imperial sponsor to their colonisation plans. Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi has detailed how the Zionist movement, backed by great power patrons, pursued its ambitions in Palestine as a settler colonial project. For the Palestinians, as Khalidi put it, Balfour’s “careful, calibrated prose was in effect a gun pointed directly at their heads.” Through the Balfour Declaration, Britain completely disregarded the indigenous Arab majority.

In a 1919 memo, Balfour himself acknowledged this, writing “the four Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes” of “far profounder [sic] import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion that is right.”

Even the leaders of Zionism framed their settlement of Palestine in imperial terms, often courting British support by touting the Zionist project’s potential benefit to UK geopolitical interests. For example, Chaim Weizmann, president of the Zionist Organisation, told C.P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, that Zionist settlement in Palestine “would develop the country, bring back civilisation to it, and form a very effective guard for the Suez Canal.”

Given events at that time, it is easy to see the declaration’s perceived benefits to imperialism. Britain had just suppressed an uprising in Ireland, while, in the Middle East, Arab nationalism was spreading. According to David Cronin, the Zionists were viewed as being like the English/Scottish Presbyterian settlers involved in the “plantation” of Ireland during the seventeenth century. Decades later, then-governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs, argued that Britain was in Palestine to create “a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism.”

British involvement in Palestine had started long before 1917, such as during the Victorian era, when pilgrimage among British tourists, missionaries and others sowed the seeds of interest in the region. However, by the turn of the century, Britain’s interest in Palestine took an imperial bent, owing largely to its strategic location. Situated on the eastern Mediterranean, Palestine provided access to the Suez Canal, an important trade route linking Britain to other imperial territories. The discovery of oil in northern Mesopotamia, an increasingly vital commodity by the 1890s, also made securing a Mediterranean terminal important to British ambitions.

The opportunity to incorporate Palestine into the imperial scramble for power came during the First World War. Amid a deadlock on the Western Front, Britain and France found themselves competing for control of the Middle East. In 1916, British cabinet member Mark Sykes and French diplomat Francois Georges-Picot agreed to secretly divide the region. However, they could not agree on control of Palestine. The French were largely pleased with this outcome as they hoped Palestine would be administered under joint Anglo-French stewardship – a condominium. However, the British were left dismayed.

Therefore, historian James Barr argues, the British immediately looked for ways to circumvent the agreement, with Zionism presenting a promising solution to their problems. By hiding behind a claim of supporting Jewish “national aspirations,” London could mask its imperial motivations and avoid angering President Woodrow Wilson, who was seen to oppose imperial rule and support self-determination. According to Barr, UK Prime Minister David Lloyd George became convinced that issuing the Balfour Declaration would thwart French ambitions and placate Wilson simultaneously.

Upon examination of the ruthless character of the declaration’s author himself, its genocidal consequences for Palestinians appear even more inevitable. Arthur James Balfour was a man of imperial violence. Between 1887 and 1891, this patrician nephew of Lord Salisbury served as Chief Secretary of Ireland. There, he authorised a regime of heavy-handed repression, once ordering police to open fire on political protesters. These actions earned him the nickname “Bloody Balfour.” He’s also responsible for introducing the Criminal Law and Procedure (Ireland) Act 1887, under which thousands were jailed for opposing British rule.

Balfour praised Cecil Rhodes’s actions in South Africa as “extending the blessings of civilization,” while also justifying both the use of Chinese slave labour in South Africa’s gold mines and British atrocities in Sudan. He opposed giving aid to people at risk of famine in India and was a lifelong opponent of Irish independence. Seen in this light, his 1917 Declaration was no kind of departure. Zionist colonisation of Palestine was merely an extension of this imperial worldview.

Antisemitism & Early Zionism

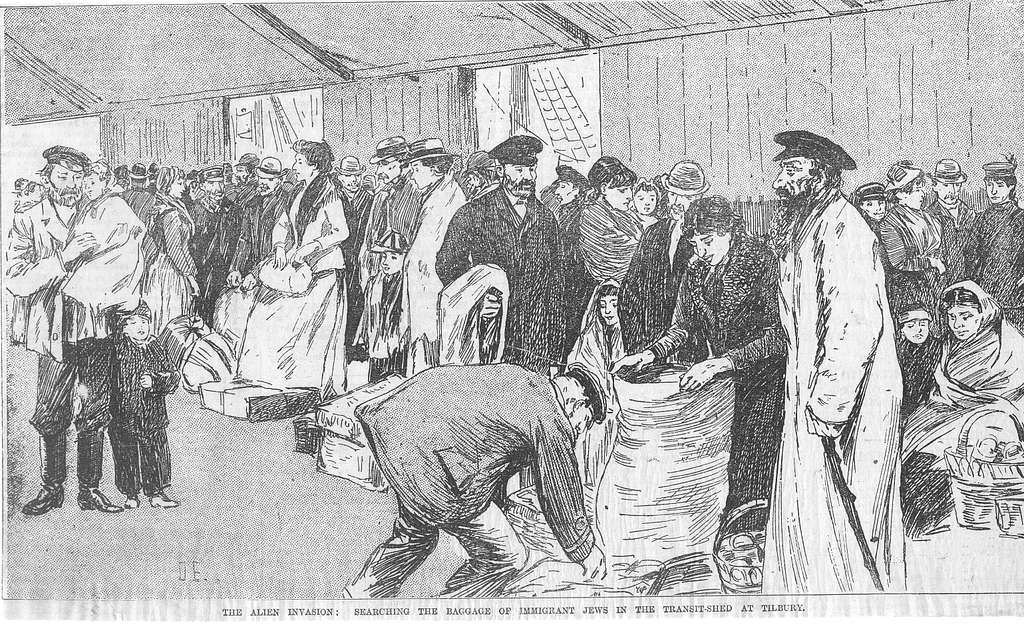

Another crucial motivating factor behind British support for Zionism was the virulent antisemitism of the British ruling class. Conspiracy theories about “Jewish power” were widespread at the time, and during the first world war they came to the fore, thanks to the scapegoating of Jews for the rise and spread of Bolshevism by British politicians and sections of the press. Russia had allied with Britain and France, while the Americans had, initially, stayed out. The majority of the world's Jews then lived in Russia, and were fleeing persecution, mostly to the US. By 1916, Britain realised that it needed US help to defeat Germany.

Egged on by Weizmann, Lloyd George’s government became convinced that if it supported Zionist aspirations in Palestine, Jewish communities in both the US and Russia would mobilise to support the war against Germany. Using their supposed “power”, these Jewish communities would keep Russia in the war and convince America to join. Robert Cecil, parliamentary Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs – and Balfour’s cousin – remarked: “I do not think it is easy to exaggerate the international power of the Jews.”

These views, shared by both Lloyd George and Balfour, had impacted the domestic programme of previous governments as well. Contrary to much glorification of Balfour today by Israel’s supporters, as UK Prime Minister between 1902-1905, his government oversaw the most anti-Jewish legislation in modern British history: The 1905 Aliens Act. This blocked the entry into Britain of Jewish refugees fleeing the Russian empire.

Despite recent attempts to whitewash the 1905 Act, the prejudices of both Balfour and its co-architect, William Evans-Gordon MP, were clear. At the Aliens Act’s second reading in the House of Commons, Balfour justified the policy by warning of the threat to British civilisation of the influx of an “immense body of persons” who “remained a people apart” and “only inter-married among themselves.” Jeremy Salt argues that this characterisation of Jews as “a people apart”, likely informed his support for Zionism. By this logic, the Jewish people wherever they resided, were a “foreign” community, fit for settlement in Palestine, not in Britain, whatever the costs to Palestinians themselves.

The same year as his 1917 Declaration, Balfour is reported to have said that antisemites had a “case of their own” and because a Jew “belonged to a distinct race” that was “numbered in millions”, one “could perhaps understand the desire to keep him down.” He wrote a glowing introduction to Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow’s book on the history of Zionism, where he praised it as a “serious endeavour to mitigate the age-long miseries created for western civilisation” by “the presence in its midst of a body which is too long regarded as alien and even hostile” but which “it was equally unable to expel or absorb.”

It goes without saying that these bigoted beliefs were completely baseless, but were consequential nonetheless. In fact, as historian Gardner Thompson argues, Lloyd George’s views on Jewish influence was a pivotal factor in his support for the Balfour Declaration. Despite the harm caused by these antisemitic theories to Jews around the world, leading Zionists decided to use the prejudices of these men to their own advantage.

Then, as now, the Zionist movement courted and appealed to racist regimes and movements. Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin argue that the defining feature of Zionism was not the choice of Palestine but “the Zionists’ willingness to ally with European imperialism to achieve its goals.” Herzl explicitly embraced the most reactionary ideals of the nineteenth century and identified with imperialist powers and their “civilising” missions around the globe. He argued that Zionism should “form a part of a wall of defence for Europe in Asia, an outpost of civilization against barbarism.”

His successor, Weizmann, maintained this stance when he noted that “we ought not to ask the British government if we will enter Palestine as masters or equals to the Arabs,” as “the declaration implies that we have been given the opportunity to become masters.” As such, Zionism was to become not merely an ally to, but an active participant in, colonisation. As Ze’ev Jabotinsky, one of the founding fathers of the Israeli right, wrote in 1925: “Zionism is a colonising adventure and therefore it stands or falls by the question of armed force,” something which he saw as more important to the future of the future Jewish state than even state-building or reviving the Hebrew language.

The Antisemitism of the Present Government

It is highly significant that the most vocal opponent of the Balfour Declaration was Edwin Montagu, the only Jewish member of the cabinet. Montagu, then-Secretary of State for India, lodged a complaint about the lobbying undertaken by the Zionists. In that memo, entitled “The Anti-Semitism of the Present Government,” he argued that by supporting Zionism, British policy would “prove a rallying ground for antisemites in every country in the world.” Once Jews are told that Palestine is their national home, he argued, “every country will immediately desire to get rid of its Jewish citizens.”

While Montagu’s positions are open to criticism – in his memo he argued that antisemitism “can be held by rational men” and that he “would not deny to Jews in Palestine equal rights to colonisation” – many of his warnings were nonetheless prophetic. He rightly predicted that Jewish settlement in Palestine would endanger its Arab inhabitants and give antisemites around the world an excuse to try to expel their own Jewish communities. According to Rebecca Ruth Gould, this document was among the most powerful diagnoses and indictments of the settler colonial mentality that continues to link the contemporary State of Israel to Britain’s imperial legacy.

This is especially important now, given the clear parallels between these logics and those of present-day support for Zionism. Donald Trump and his fundamentalist Evangelical Christian base, Hungary’s Viktor Orban, India’s Narendra Modi, as well as the former autocratic leaders of Brazil and the Philippines, have all been welcomed with open arms by Israel and its allies. At the same time, right-wing movements and figures who trade in dog-whistle politics and racist campaigns are excused by Israeli politicians and Israel’s chief supporters. As long as they support colonial violence committed against Palestinians, white supremacists and ethno-nationalists alike are embraced by Tel Aviv.

Comparing Balfour’s 1917 declaration with the 2017 IHRA working definition of antisemitism, one hundred years apart, Ruth Gould demonstrates how they both reflect a dangerous tendency of imperial powers to homogenise communities, ignore different voices within those communities and subordinate minority rights for political motivations. This leads to Jewish interests being “reduced to political instruments,” in which Jews become “proxies for pursuing other agendas,” with Palestinians made to pay the price.

Both documents acquired political significance not to fight antisemitism, but to displace it. Balfour’s pledge erased the rights of an entire people – the Palestinians – while today, the IHRA works to silence their ability to even articulate their own history and lived experiences. While Israel carries out a genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, its major allies, including Britain, hide behind claims to be supporting Jews in the fight against antisemitism while enabling the Zionist colonial project to uproot and destroy Palestinian lives.

For Palestinians, this history is ever-present – they are forced to live with the effects of the Balfour Declaration every day. Whether under Israeli apartheid across historic Palestine or dispossessed around the world waiting to return, Palestine’s indigenous Arab population have all been affected by Balfour’s pledge in some way. Formalising the process of their expulsion, this Declaration fits within a long history of British imperial crimes. Given that this support never ended, it is imperative that its origins and legacies face a reckoning.

A. Bustos is a researcher with a masters degree in Near and Middle Eastern studies from SOAS, University of London.

There’s no corporation or big advertisers behind Vashti – we're a workers' cooperative and rely on small donations to keep running. Support our journalism to help break the consensus.

To donate once, click here. To donate monthly, click here.

Author

A. Bustos is a researcher with a masters degree in Near and Middle Eastern studies from SOAS, University of London.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.