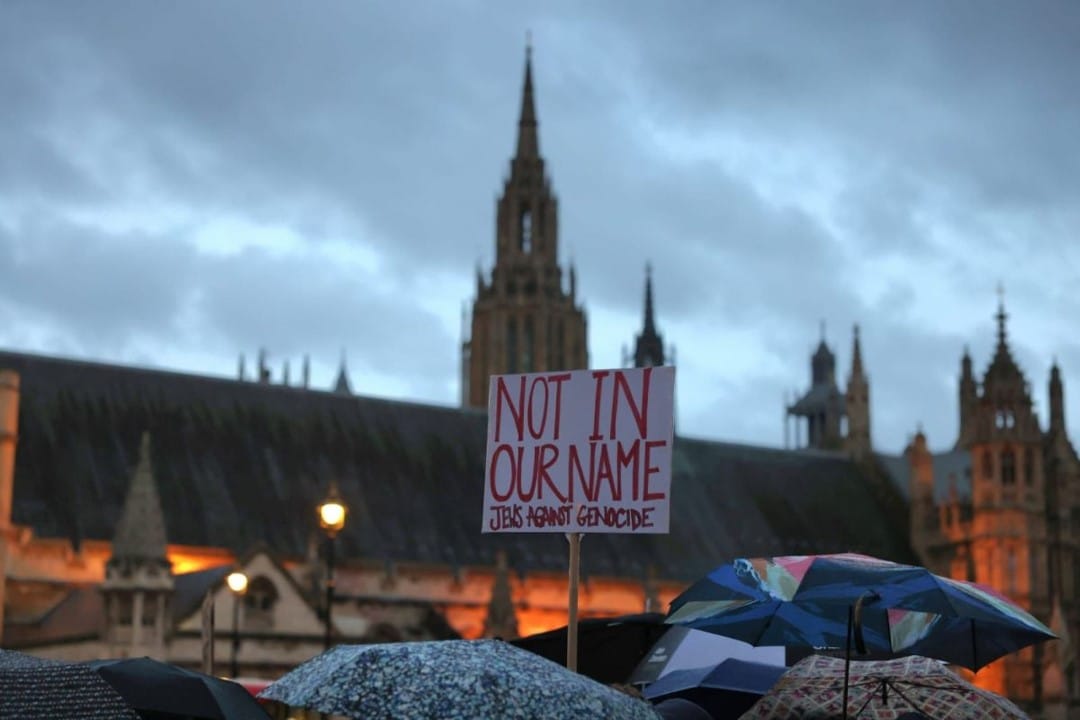

Not in our name

'To those who defend Israel’s pummelling of Gaza and the status quo that preceded it, I say: do so in your name, not mine.'

This article was originally published on Tribune.

I hadn’t planned on writing anything about current events, thinking it best to let Israelis and Palestinians speak for themselves. But this week a family member told me about a conversation he’d had with non-Jewish friends in Britain who were worried about speaking about the catastrophe unfolding in the Gaza Strip for fear — unwarranted, in his case — of offending him or being accused of antisemitism.

So to those friends, I hope you can take these words as a plea from one Jewish woman: please speak out about Palestine. Please, place every ounce of pressure you can muster on our government and opposition to change their positions, which have so far largely amounted to a green light for genocide.

Despite the common framing, the Jewish community in Britain is not homogenous. In previous years, I’ve shared the frustration of others that we should be asked to comment on or feel particular ways — or indeed any way — about a situation that many of us have no connection beyond the fact of being Jewish.

Speaking about Palestine is not a precondition for a Jewish person to be treated with respect, and not doing so does not justify abuse, particularly when many Jews are mourning the murder of their own loved ones. Nonetheless, this is a moment in which diaspora Jewish voices carry weight, and I have drawn strength in recent days from growing numbers willing to oppose the collective punishment that many seem to expect us to rally behind — by anti-apartheid demonstrators, words in dissenting outlets, by a Muslim friend recounting that when he was harassed on the tube for carrying a Palestinian flag, two Jewish women intervened to help him.

Surveys from 2023 and 2015 show that majority British-Jewish opinion is not as uncritical of Israeli policy as many non-Jews might believe. If you listened to certain politicians and public figures you would think that there was no hope for dialogue, no hope for coexistence, no hope for a safe and dignified future for everyone. The community by which I am surrounded proves that wrong.

I don’t blame friends, both Jewish and non-Jewish, for their worries over discussing Palestine. I blame the absurd scaremongering around peaceful movements like the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) and actions such as waving a Palestinian flag. I blame the one-sided narrative about Israel I was taught as a child, which left me struggling for years to understand the call for Palestinian liberation as anything other than antisemitism.

I blame the tiny minority of antisemites in the vast campaign for a free Palestine whose behaviour serves nobody but the most aggressive opponents of the Palestinian people. I blame the Israeli government for justifying its violence as the sole guarantor of Jewish safety worldwide. I blame leaders who have decided that civilian deaths are only sometimes a legitimate cause for distress and anger, and a whole political class that finds it useful to leverage Jewish fear and mourning for its own ends.

There are lines that need to be drawn. Opposing the actions of the Israeli government is not the same as supporting the atrocities of Hamas. Neither is providing the relevant history against which all this violence is taking place — history which most recently includes a 17-year-long blockade on Gaza that has limited the movement of food, building materials, and people throughout the area, and which itself flows on from years of occupation and the Nakba. Acknowledging such context is not apologism. Historical context is a precondition for progress toward any kind of just peace.

Here are a few statistics that show what life in Gaza is like as a consequence of that history. According to the WHO, 839 patients died while waiting for Israeli permits to allow them to leave Gaza for medical treatment from 2007-21. In 2021, unemployment in Gaza was 47 percent, and rolling power cuts averaged 11 hours a day. In 2022, 65 percent of Gazans lived below the poverty line, and four out of five children — children — in the Gaza Strip lived with depression, grief and fear. All these figures predate the current bombardment.

Now, over two million people are being squeezed into an area unable to support them, with profound limitations on food and water, while Israeli bombs collapse infrastructure and claim yet more lives. Those who say criticism of the Israeli government or calling for Palestinians to live free lives is tantamount to anti-Jewish hatred imply that keeping other human beings in such conditions is somehow intrinsic to our Judaism. That implication is far more offensive to me than anything I have witnessed at a pro-Palestine rally.

Organisations that have been vocal about Israel’s blockade and occupation include the UN, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Save the Children, among many more. Some describe Gaza as an ‘open-air prison’. Some say Israel’s policies constitute apartheid. The civic standing afforded these bodies means that their conclusions cannot be dismissed as bigoted or irrelevant, as hard as some might try.

The consequences of insisting otherwise for Palestinians are evident, but if you want to talk about the safety of Jews, I also fear the consequences for Jewish communities. It seems almost too obvious to state, but history makes it clear that Jews also need the protection of universal standards of human rights. Jews are not safe in a world that considers those rights mutable, apartheid acceptable, genocide justifiable. Jews are not safe in a world in which the cordon sanitaire against violent fascism is broken, wherever that fascism is.

The more direct failings of apartheid as a strategy to ensure the safety of Israeli Jews were made clear this week. As Gideon Levy wrote in Haaretz, ‘it’s impossible to imprison two million people forever without paying a cruel price.’ To state this, too, is not to excuse Hamas’s attacks on civilians or to belittle the fear, grief and rage so many are feeling. It is to acknowledge that understanding how and why violence happens is the only way to bring it to an end.

To put it down simply to ‘Islamic bloodlust’ is to say there is no answer other than extermination; to consign human history to a series of massacres committed by one group against another, forever. It is not a conclusion anyone should be willing to countenance.

A Haaretz editorial published the day after the attacks was unequivocal in blaming Benjamin Netanyahu, his ‘government of annexation and dispossession,’ his foreign policy ‘that openly ignored the existence and rights of Palestinians.’ If an Israeli newspaper can publish those words as their nation mourns, if the parents of hostages and the survivors of massacres have the strength to call for political solutions and for peace, I see no good reason for us here in Britain, whatever our beliefs, to be silent.

To those who still feel the need to defend the pummelling of Gaza and the status quo that preceded it as more homes crumble and the death toll of innocent people climbs ever higher, I say: do so in your name, not in mine. ▼

Francesca Newton is assistant editor at Tribune and an editor at Vashti. She currently lives in Melbourne.

Author

Francesca Newton is assistant editor at Tribune and an editor at Vashti. She currently lives in Melbourne.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.