Marching on together

Remembering the tailors' strikes of 1888, when Leeds' Jews revolted.

By the late 19th century, Leeds was firmly established as a hub of British Jewish life. The community had grown in tandem with the textiles trade from a tiny regional settlement dependent upon Sheffield for kosher meat to a thriving metropolis revolving around the Leylands area north of the city centre. Rumours of economic opportunity spread back to Eastern Europe, and young Jewish men were recruited to join Leeds’ sub-divisional tailoring trade.

Contrary to local folklore, Leeds was not an accidental stop-off on the Hull-Liverpool route. For most new arrivals the city was a destination (it’s rumoured some immigrants came to London with only a slip of paper reading “LEEDS”). Lacking the established Anglo-Jewish presence of London or Manchester, Leeds’ Jews built their own communal infrastructure, sometimes imitating but often inventing, new modes of communal relations.

These new arrivals weren’t simply a mass of penniless peddlers, nor a cabal of merchant bankers. Their class composition was – as is often the case – more complex. Like the immigrant communities that preceded and followed them, Jews in Leeds grappled with class as they did with their gender, religion and race – in a messy, intersectional web. Leeds’ Jews were relatively homogenous compared to other communities – most of the 20,000 came from towns around Kovno in Lithuania – but contemporary sources point to strings of disagreements and differences, most prominently between the Jewish tailoring workers and their Jewish bosses.

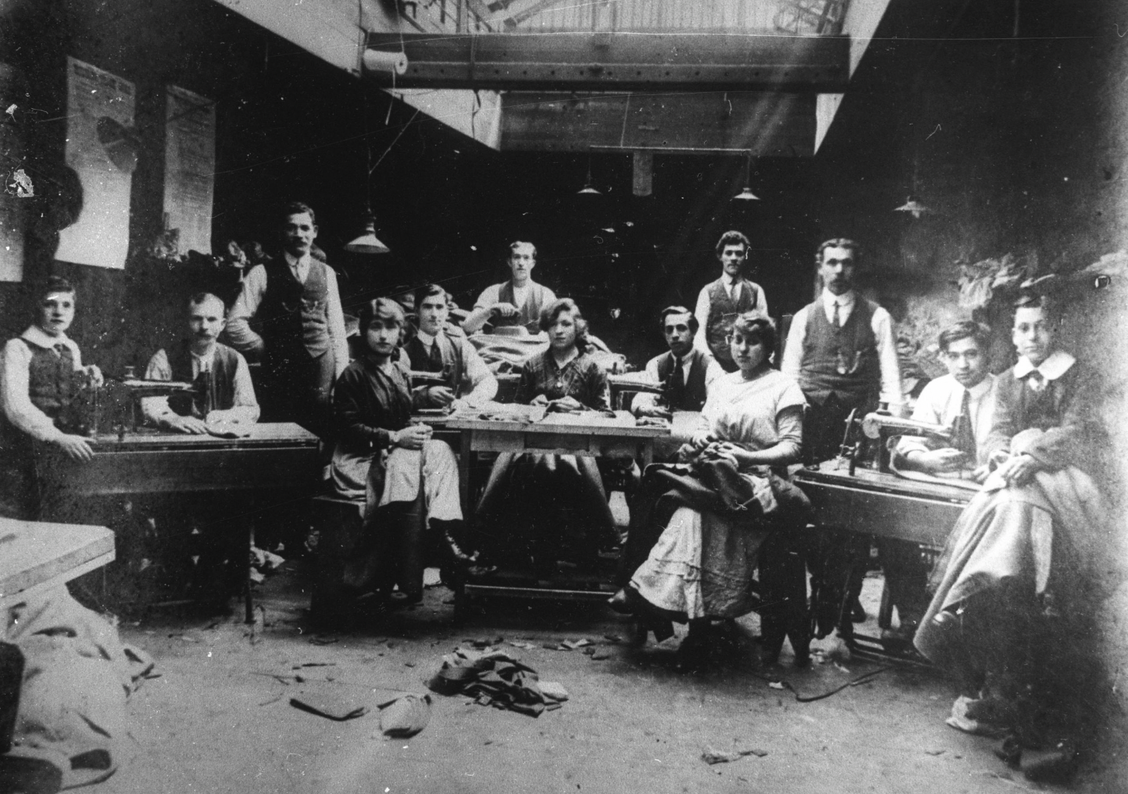

Some Jewish migrants received textiles training in Europe and saved enough money to set up crude workshops – essentially sweatshops – which employed fellow Jews. Workers were expected to do 14-hour days on meagre salaries. Conditions were so intolerable that they were investigated by a House of Lords Select Committee together with The Lancet medical journal. In a system which relied on cheap labour and poverty wages, Jewish migrants were both the exploiters and the exploited.

It didn’t take long for Jewish workers to start organising, with Jewish tailors establishing the first clothing workers union in Leeds in 1876. Although it struggled during the recession of the 1870s, by 1885 the Jewish Workers Trade Society was ready for its first major strike. The decision to strike had widespread support from across the local and national community, including from the Leeds Express and even the Jewish Chronicle. Early leaders of the labour movement, such as Liberal politician James Rowlands, came to show support for the striking workers who demanded reduced hours and better pay. After six hundred workers walked out, the Jewish Masters Association called a meeting with the union at the Belgrave Street Synagogue. They agreed to reduce the work day by one hour without loss of pay. The organisers would later claim this was the first Jewish-led strike in Britain.

Unfortunately these gains were short-lived, and in 1888 the Jewish workers picketed once more – this time for a far larger, longer but less successful strike. A total of 3,500 Jewish tailors, pressers and machinists joined the strike – almost half of the Jews in Leeds at that time – leading some historians to label it ‘The Jewish revolt of 1888’. Ultimately, the strike began to crumble as funds dried up, and masters soon implemented blacklists, causing union membership to collapse. But despite the lack of material success, it provides many lessons.

Firstly, these workers were pragmatic. As socialists, the Jewish unions were seeking not just the abolition of middle managers, masters and sweatshop labour, but of capitalism itself. Yet that did not stop them from negotiating strategically and making tangible demands to alleviate miserable working conditions in the short term.

The organisers were also embedded in their communities. Unlike in London, where labour organising often came either from above, in the case of Samuel Montagu’s Jewish Tailors and Machinists Society, or from outside when émigré radicals clashed with local religious leaders.

Whether out of necessity or principle, these strikes were also at their core cross-communal. From its foundation, the union counted on the support of non-Jewish organisers and organisations, notably both the liberal Trades Council and the Socialist League, who held a common interest in improving Jewish working conditions for the good of all workers. When Jewish bosses used the press to stoke antisemitic fears about Jewish tailors undercutting the pay of English women, the union organised a solidarity rally with English women. When Jewish bosses used their communal power to cut off credit lines at kosher shops, the local Trades Council organised a benefit concert at the City Varieties Music Hall to bolster their strike fund.

These cross-communal collaborations would have a lasting impact. Facing a system built upon the separation of migrant and English labour, Leeds’ Jewish unionists were still able to join forces with English factory workers. By 1915, Leeds’ Jewish tailors made up the second largest constituent of the United Garment Workers Trade Union – composing almost a third of its members – owing largely to their relationships with other tailoring unions. Leeds’ own Moses Sclare served as its founding treasurer, and through these national connections, successfully led a resolution at the TUC general conference banning “bedroom workshops” where sweaters worked and slept in the same cramped room.

This cross-communal solidarity is even more staggering given the context. At a time when many across the left saw migrants as a threat to the “English working class” – with anti-semitic rallies held by the British Brothers League across London’s East End – Leeds’ unions offered a hopeful alternative.

Unfortunately, we see similar rhetoric today, even within Jewish spaces. The false notion that immigrants threaten “British’ workers” living standards was levelled at our great-grandparents. Looking back 140 years, we see a repudiation of this zero-sum approach, not just in the famous Jewish radical centres of the East End, but in Jewish communities often dismissed as provincial backwaters. A 1910 editorial from the Leeds-based Anglo-Jewry magazine captures this spirit:

“It imagines, that as far as English-speaking Jews are concerned, all the wisdom, all the brilliance, all the genius has been drawn from all over the world into the one great vortex, London. […] For Jews exist, and in large numbers too, outside London, who are not altogether dumbasses nor aping mules.”

We have much to learn from our history – both the successes and failures. For those of us interested in organising within and beyond the Jewish community today, the past is an invaluable resource which should not be confined to the boundaries of the M25. As the current wave of strike action runs into the new year, we would do well to remember this history. Jewish history is a part of labour history, and labour history a part of Jewish history.▼

Toby Kunin is a Jewish student and activist from Leeds. He writes about race, migration and the diaspora.