Labour's Zionism has a past, but should not have a future

Keir Starmer's staunch defence of Israel is no anomaly, but is rather in keeping with a tradition of Zionism with deep roots in the UK’s Labour Party.

Since assuming leadership of the Labour Party in 2020, Keir Starmer has gone to great lengths to emphasise his support for the State of Israel. One incident which showed just how far he would go took place in February 2024 when, more than four months into Israel’s bloody invasion of Gaza, Starmer resisted a motion calling for an immediate ceasefire, defying “long-established conventions” in parliament to ensure the substance was watered down.

For those coming of age during the eras of Ken Livingstone and Jeremy Corbyn, it might be tempting to see Starmer’s hesitance to stand in solidarity with Palestinians as out of step with Labour’s noble traditions. The truth is somewhat more complicated. For much of its history, Labour, and particularly the left of the party, has supported Zionism fervently.

Taking a closer look at the intertwined relationship between Labourism and Zionism that developed in the two movements’ early histories (particularly the period between the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the establishment of the Israeli State in 1949), both similarities and important differences between present and past Labour Zionism come into view.

Labour’s historic Zionism

Support for Zionism was once widespread across the Labour Party, including among its leading figures. Two examples of such leading figures are Ramsay MacDonald and Aneurin Bevan. Both men, whose careers overlapped, held strongly pro-Zionist beliefs, despite leading opposite ideological wings of Labour’s left-right spectrum.

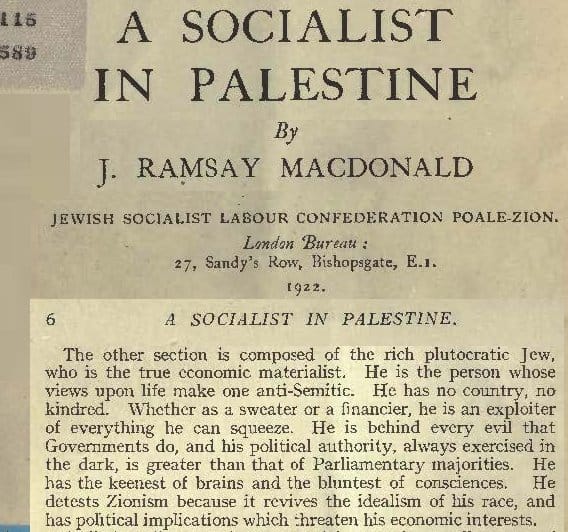

MacDonald, who became Britain’s first Labour prime minister in 1924, was an early, committed supporter of the Zionist movement, and gave the Balfour Declaration “his full backing” in 1917. In his 1922 travelogue A Socialist in Palestine, he described the Arab population as too backwards to make proper use of the region’s resources, believing that the Zionist project would bring economic development benefiting both Arabs and Jews.

This perspective fits with his views on colonisation and imperialism. MacDonald was part of a Labour tradition which believed that an empire run by socialists could operate in fundamentally different ways to one run by capitalists, and that a socialist empire could help to bring development and progress to poorer parts of the world.

MacDonald also belongs to a storied history of antisemites supporting Zionism, from Arthur Balfour to Anders Breivik. In the same pamphlet in which he defended Zionism, MacDonald wrote of “the rich plutocratic Jew,” with “no country, no kindred,” as “an exploiter of everything he can squeeze” and “behind every evil that Governments do,” “whose views upon life make one anti-Semitic.” In this sense, MacDonald was an early adopter of the dichotomy between “good” Zionist Jews, those rooted in place, and “bad” rootless, cosmopolitan Jews, which continues to this day. Towards the end of his life, he was even reluctant to criticise Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews.

To the extent that MacDonald is thought about today, it is as the leader who betrayed the Labour movement and went into coalition with the Conservatives, leading to his expulsion from the party. Bevan, on the other hand, is seen as one of the British social-democratic left’s most important and successful politicians of all time, best known for the creation of the NHS.

Bevan was an internationalist, a strong advocate for the cause of the Spanish Republicans and the movement for Indian independence. Nevertheless, as the Jewish Chronicle reminds us, he was also “an ardent Zionist,” supporting Zionism from before Israel’s founding through to the end of his life in 1960. Even when tearing apart the Eden government’s actions in the Suez Crisis of 1956, Bevan tellingly exempted Israel from criticism for its role in causing the crisis. He was a friend of Yigal Allon, an IDF general turned politician who briefly acted as Israel’s prime minister. In the late 1940s, Allon played a leading role in ethnically cleansing hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and, two decades later, as Labour Minister, developed a “plan to annex large swaths of the West Bank, including the Jordan Valley and greater Jerusalem area,” which “served as a blueprint for the Labor-led governments of the next decade.”

Bevan’s Zionism was by no means out of sync with the wider Labour left. For a long time, the only attention given to the interests of Palestine’s Arabs in Labour came from right-wingers like Ernest Bevin. As Paul Kelemen noted in The British left and Zionism: History of a divorce – an important source for this article – the first notable left-wing MP to advocate for the Palestinians emerged only in the 1950s (the pioneering feminist Edith Summerskill).

At its 1944 conference, Labour endorsed the removal of the Palestinians to make space for Jews. And yet, throughout the decade, the main pushback to Labour’s Middle East policy from left MPs was that it was insufficiently pro-Zionist. In the late 1940s, as Palestinians were dispossessed on a massive scale, the major media organs of Labour’s left, particularly the New Statesman and Tribune, essentially endorsed the mass displacement of Palestinians while minimising their suffering.

Why was Labour so pro-Zionist?

In the interwar period, part of the appeal of Zionism for Labourites was its socialist bent. They were immensely impressed with the kibbutz movement’s achievements, and often praised the Histadrut trade union body, which organised the vast majority of Jewish labour in Palestine.

Notably, during this period, Labour Zionism had little to do with appealing to Jewish voters, as the issue was not particularly salient for working class Jews in Britain. As Kelemen points out, Zionists in the UK struggled to win the support of workers, with the movement’s base of support largely among the middle classes at the time.

For some Labour Party reformists, Zionism was an exciting alternative to revolutionary Bolshevism. Kelemen notes that Ramsay MacDonald “liked its emphasis on constructing the new society rather than on class struggle,” while Yosef Gorny recounts how, in the late 1920s, R.H. Tawney, Britain’s leading socialist historian at the time, considered “the achievements of the Jewish labor movement in Palestine” to be “the only constructive reply to Bolshevik Communism.”

Colonialist thinking also played a role. Left-wing Zionist MP Richard Crossman was more explicit than most in describing Zionism as “merely the attempt by the European Jew to rebuild his national life [...] in much the same way as the American settler developed the West,” with “the Arab'' here playing the passive role of “the aboriginal.” Many others in Labour emphasised the reactionary nature of Arab feudal leaders and the progressive role socialist colonists could play.

An important factor contributing to the predominance of Zionist views among Labour parliamentarians was the lobbying undertaken by the socialist-Zionist movement Poale Zion (“Workers of Zion”). From 1920 onwards, Poale Zion worked diligently to build personal relationships with Labour politicians, arranging them visits to Palestine and cementing the perception that the Zionist movement was aligned with Labour in its fundamental values and aspirations. Unfortunately for the Palestinians, they had no similar movement able to advocate for their interests or win politicians over to their perspectives.

The left outside Labour

These ideological commitments were not inevitable, however, as is clear from criticisms of Zionism emanating from left-wingers outside the party. Labour’s leading rivals on the left in the 1930s, the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), provide clear examples.

The ILP helped found the Labour Party but split off from it in 1932. In the years after disaffiliation, the ILP criticised the Zionist movement for acting as a tool of imperialism and for discriminating against Arabs. The party was equally critical of Arab leaders, advocating unity of the Jewish and Arab working classes as the only path forward.

In the 1930s the CPGB was even more anti-Zionist than the ILP. Unlike many in Labour, the Communists held that a socialist colonial policy was impossible, and they applied this to Palestine. They were the strongest supporters of the Great Palestinian Rebellion of the late 1930s, and, as Kelemen describes, “the only significant voice among intellectuals and the labour movement to articulate the Arab nationalist point of view.”

Like the ILP, the Communists criticised both Zionism and Arab elites, advocating the unity of Jewish and Arab workers. They were particularly critical of the Histadrut’s exclusion of Arabs and its “Hebrew labour” policy, which aimed to replace Arab workers with Jews. The CPGB pointed out that deliberately increasing Arab unemployment would only deepen divisions in the working class, and could not in any way be defended on socialist grounds.

However, when the Soviet Union reversed its opposition to Zionism in 1947, the CPGB loyally followed suit, immediately abandoning its prior positions. After violence broke out in Palestine following the UN’s partition resolution, the Communist Party and its newspapers paid no attention to Palestinian suffering, instead defending and glorifying the Zionist paramilitary Haganah - a precursor to the IDF - in similar terms to the Labour left’s newspapers.

Criticism of Zionism and Labour’s support for it also came from left-wingers outside the party structure. Anarchist writers like Albert Meltzer and Vernon Richards were scathing in their opposition to Zionism as a solution to the problem of antisemitism, and, similarly to the ILP and CPGB, pointed to the unity of Arab and Jewish workers against their elites and imperialism as the only hope for the region.

A split in the party: how the Labour left’s Zionist romance ended

Over the decades, the Labour left’s position changed, with the Six Day War of 1967 marking a turning point. Tribune began showing a concern for Palestinian refugees which it had lacked in 1948, and a split emerged among left MPs, between those who were critical of Israel’s actions and those who remained steadfast in defending the state.

In the years following the war, the edifice of left-wing Zionism began to crumble. It became harder to paint Israel’s actions as defensive or necessary to avert another Holocaust, and more difficult to ignore the negative impacts of its policies on Palestinians. By 1970, even Richard Crossman, possibly Labour’s most committed Zionist, showed signs of discomfort with the direction the state was taking. Israel gradually shed its socialist image, a shift made clear with the election of its first openly right-wing government in 1977. Unlike their Labour Zionists predecessors, the new Likud government made no pretence of willingness to give up land acquired by Israel through its various wars.

With Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, left-wing MPs had little choice but to reconsider their perspectives. The horrific massacre of Palestinian refugees in the Sabra and Shatila camps, in particular, represented the final straw for quite a few. In response, influential left-wing Labour parliamentarians such as Eric Heffer and Tony Benn, who had previously been strongly pro-Zionist, felt compelled to resign from Labour Friends of Israel – a pro-Israel lobby group that continues to operate today, works closely with the Israeli embassy and refuses to reveal its funding sources.

On the global stage, Israel had by this point unequivocally aligned itself with US militarism, acting in many ways as an extension of American interests in the Middle East. It became a leading supplier of weapons and training to militant far-right groups and dictatorships across Latin America, as well as an extremely close economic and military partner to apartheid South Africa.

While left-wing Jewish MP Ian Mikardo clung to his support for Israel until the end of his life, he was very much the exception. Another exception was two-time British prime minister Harold Wilson, who seemed to shift to a more pro-Israel position in the 1970s, as most others mellowed in their Zionism. Wilson was no longer on the left of the party by that point, however.

By the 1980s, Israel-Palestine had become a more pronounced left-right issue within Labour. The academic June Edmunds describes how the party’s policies became much more pro-Palestinian thanks to the strength of the left in the early 1980s, but then moderated significantly as Labour moved rightwards under Neil Kinnock. Kinnock, much like Starmer almost 40 years later, was keen to draw a sharp distinction between himself and the left of the party, who he held responsible for Labour’s abysmal performance in the 1983 election. One way in which he sought to do so was by emphasising his position as “a strong supporter of Israel.” Under his leadership, Labour’s National Executive Council (NEC) replaced its prior endorsement of a Palestinian state with a vaguer commitment to self-determination and a homeland. The divide between a more pro-Palestine Labour left and more pro-Israel Labour right has been clear ever since.

Learning from past mistakes

In reviewing this history, we can trace a trajectory in which broad support for Zionism among Labour parliamentarians, fueled by the belief in the movement as a promising experiment in socialist transformation, gradually gave way to disillusionment among the party’s left, as violent and ethnonationalist realities began to emerge. This early Zionism, despite being selective and Orientalist, grew from a genuine sentiment of socialist internationalism, based on hope in the possibility of building a new type of society.

The present-day Labour right retains the party’s past dehumanisation of Palestinians, but sheds this idealism. Labour’s current support for Israel, particularly in the aftermath of October 7th, has more in common with the cynical and cowardly support offered to other murderous and repressive governments, like that of Saudi Arabia, with which the UK (and US) maintain alliances.

Recent attempts to resurrect the Labour left’s inter-War Zionism are ultimately futile. Left-Zionism could not survive contact with the reality of the Israeli state, and it is, by now, long-dead. Rather than mourn its demise we should instead recognise that those who, in the 1960s through 1980s, broke from the Labour Party’s traditional stance on Zionism, have largely been proved right by history.

Daniel Lewis is an activist and writer currently working in the charity sector.

There’s no corporation or big advertisers behind Vashti – we're a workers' cooperative and rely on small donations to keep running. Support our journalism to help break the consensus.

To donate once, click here. To donate monthly, click here.

Author

Daniel Lewis is currently completing a degree in Philosophy and German at the University of Leeds.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.