The Soviet-Jewish experience, revisited

A new book presents ambivalence as its core motif.

This Passover, Jews around the world were encouraged to leave a seat open at their Seder table for Evan Gershkovich, a Wall Street Journal reporter detained in Russia since 29 March on spurious accusations of espionage. The campaign, initiated by Gershkovich’s colleagues, drew on the journalist’s background as the son of Jews who emigrated from the Soviet Union, deliberately invoking similar Passover-based “ritualized protest” that was central to the movement to free Soviet Jewry beginning in the 1960s.

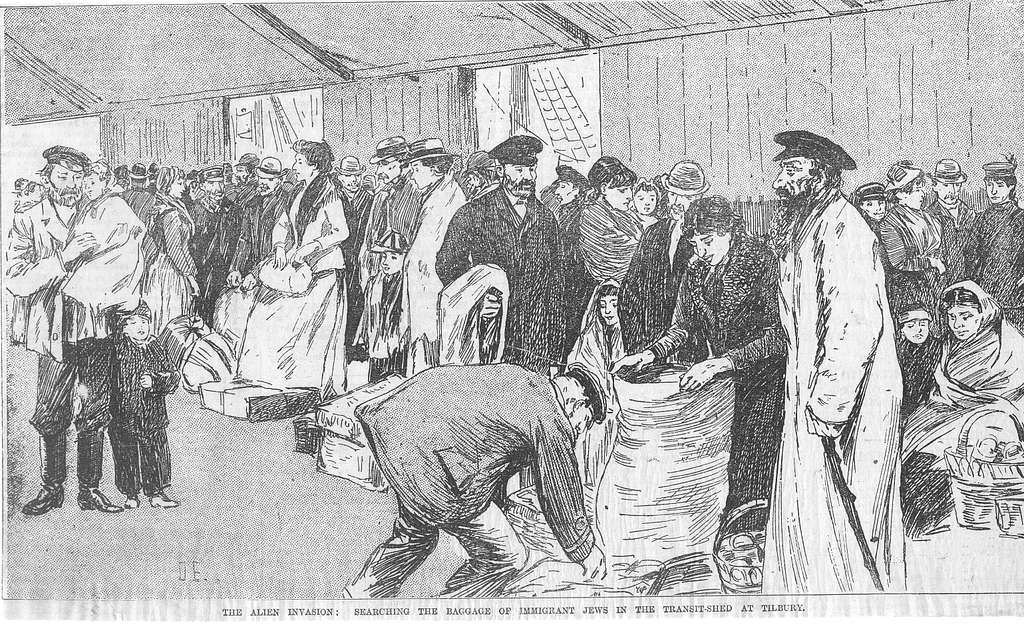

At that time, groups such as the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry in New York (led by German-British activist Yaakov Birnbaum) and the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry in London (known as the 35s) developed a publicly Jewish form of protest to the Soviet Union’s emigration restrictions, destruction of Jewish institutions, imprisonment of dissidents, and various anti-Jewish campaigns carried out in the courts and media.

Importantly, the forms of protest that developed in the US and the UK were shaped by historical forces particular to the time: the six-day war and Israeli ascendancy; cold war notions of western superiority; and increasing public awareness of the facts of the Holocaust, which led to an urgent desire to prevent it from recurring.

Gershkovich’s detention takes place in a different environment altogether, both in eastern Europe and in centres of activism in the west. As the situation develops, it is worth thinking critically about the merits of reading the experience of Soviet Jewry onto his arrest and, in turn, reproducing corresponding forms of protest (which themselves may be embedded with potentially uncomfortable meaning).

In this week’s Pickle, historian James Benjamin Nadel guides readers through Sasha Senderovich’s new book How the Soviet Jew Was Made, which explores the Soviet-Jewish experience from its beginnings – before, as Sendorovich writes, “the Soviet Jew became a figure that needed to be ‘saved’ and reunited with expressions of Jewish identity legible to Jews in the West”▼

Evan Robins.

Neither here nor there

by James Benjamin Nadel

A Century of Ambivalence – that was the title Zvi Gitelman chose for his history of Russian Jewry since the late-19th century, which remains the standard account some 20 years after its publication. Over the subsequent two decades, historians and literary scholars alike have considered countless aspects of the ambiguous relationship that Russian Jews maintained with the Soviet project. Their monographs have especially fleshed out the period between the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 and the Stalinist purges of 1936-38, when the maturing state apparatus was still willing to make compromises with group representatives in order to consolidate its rule.

Scholars have plumbed the depths of the Soviet-Jewish experience and discovered elements of Jewish life from before the revolution that persisted despite state oppression, or that were even made anew with government support. Yiddish literature, Bundist cadres, theatre troupes, popular songs of the period, religious practices – all of these have been resurrected, in part, to demonstrate that the Bolshevik regime did not and could not simply obliterate the traditions of eastern European Jewish culture with a snap of its totalitarian fingers. Rather, Soviet Jews maintained “some expressions of Jewishness” that sat alongside – sometimes awkwardly, sometimes harmoniously, and sometimes in direct opposition to – state priorities. Integration progressed, ambivalence persevered.

Now, with his new book How the Soviet Jew Was Made, Sasha Senderovich has brought this ambivalence itself under the microscope, and presented it as a core motif of Soviet-Jewish being. Unlike his predecessors, Senderovich examines moments in Soviet art – Russian- and Yiddish-language novels and films – where the “Soviet-Jewish figures” reflect, or reflect on, their own transitory existence as Jews that are not yet Soviets and Soviets that are no longer only Jews.

As such, we learn that Moyshe Kulbak’s The Zelmenyaners features characters dispersed from their ancestral home in the Pale of Settlement – to which Russian Jews were confined until the revolution – yet are still aware of their attachment to it. A descendent of the family is recognised on a train due to the “idiosyncratic” smell of his clan, which he cannot cast off despite his new appearance, and with which all former residents of the Pale were familiar. The characters carry with them objects salvaged from the demolished courtyard where the family resided for a century, and these common household items become artefacts imbued with Jewish historical meaning.

The past sticks to these figures and their possessions even as their physical movement seems to mark a disappearance into Soviet homogeneity. As a contemporary critic put it with chagrin, the characters of Kulbak’s novel represented the “generation of the desert” – forever moving towards the promised land, but never quite arriving.

Fitting this metaphor, when describing Birobidzhan – the area chosen by the Soviets in the 1930s to be the new homeland of Soviet Jewry – the texts that Senderovich discusses spend more time describing the destruction of the old Jewish communities of the Pale than the supposed splendours of this new far-eastern province. By the same token, Senderovich demonstrates that Soviet films – even as they include the archetypes of both the new Soviet man and the unreformed shtetl Jew – feature and linger on characters stuck between these two extremes. In each of these instances, as he puts it, “the Soviet Jew failed to arrive”, with their existence defined more by a sense of becoming than by an achievement of having become.

Ambiguity of this kind could breed possibility. In reading the stories of Isaac Babel, Senderovich shows that Soviet Jewish characters could avoid danger by acting in the mode of the “trickster”, fluent in both Soviet and Jewish “verse”. But, more often, unease permeates these texts.

Under the shadow of insecurity

Recent historical treatments of the period have excavated the lived experience of Jews as a minority group within the Soviet Union. The threat of ethnic violence cast a certain pallor on daily life and forced Jews to grapple with just how precarious their safety might be.

Elissa Bemporad has illustrated that even as Jews integrated into the Bolshevik political programme and discourse in urban areas, those that remained further from the centres of Soviet power constantly relived the trauma of the pogroms; attacks on Jewish communities during the civil war left tens of thousands dead and half a million homeless.

Jeffrey Veidlinger has explored the practical steps that Jews took to confront a fear of extermination that lingered on in the decades-long aftermath of these same onslaughts – an ambient awareness that preceded the destruction of eastern European Jewry in the Holocaust. Hastily constructed mass graves erected after 1917 dotted the landscape of the Jewish mental geography, and their eerie presence could call into question the headlong thrust into a Soviet tomorrow.

Senderovich similarly finds that unmourned violence acts as an unsettling background for the “gothic” plot of David Bergelson’s Yiddish novel Judgment, where the Soviet-Jewish worldview is “haunted by spectral remnants” of the pogroms. Even when Bolshevik Chekists – members of the early Soviet secret police – proclaim that they aim to protect Jews from the horrors they recently witnessed, Bergelson’s characters look somewhat askance, unsure that Soviet officials have the staying power to deliver on this promise.

Powerlessness, insecurity and trauma suspended the Soviet-Jewish figure in a hesitant middle ground. Senderovich’s achievement is in deftly illustrating the tensions of this moment, when speculating on the outcome of the revolution for eastern European Jewry could provoke both great hope and visceral dread in a single text.

Possibilities abound for future research that pursues Senderovich’s findings while exploring different contexts. For instance, one might investigate the degree to which this ambiguity marks the art of other Jewish milieux – especially that of Palestine before and after the establishment of the state of Israel.

The Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever, shortly after the Suez crisis of 1956, imagined exploring the Sinai peninsula and finding there not only the Zionist dream fulfilled, but also the ghosts of his life in eastern Europe. Upon approaching the cliffs of Wadi Feiran – the site where Moses supposedly called forth water from stone – it is his “Lithuanian mother” that appears before him. Does such layered imagery reflect the indeterminacy of a “Jewish-Israeli figure” in the same way as the Soviet texts that Senderovich has studied? Is a state of “becoming” central to Jewish literary representations in a more general sense?

Alternatively, one might seek other examples where cultural traditions associated with a particular ethnic group encountered and collided with the central tenets of the Soviet project. The transformation of shtetl life was a self-proclaimed benchmark of success for certain representatives of the Soviet government. But this was similarly the case for programmes aimed at the nomads of the circumpolar region, to take one other case where the Soviet state attempted to impose and induce a wholesale civilisational shift.

Officials inherently viewed their projects as protracted, never as fast to resolve as they ought to be or as was necessary for the success of the revolution. With this as the dominant discourse, anachronism was a common mode of being in the Soviet Union. Perhaps, the same can be said of ambivalence.▼

James Benjamin Nadel is a PhD candidate in the History department at Columbia University and a former ASEEES Cohen-Tucker Fellow.

Author

James Benjamin Nadel is a PhD candidate in the History department at Columbia University and a former ASEEES Cohen-Tucker Fellow.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.