In Czechia, dissenting diasporism forges new paths

A declaration of independence from the "voice of Israel in Europe."

Visual artist Pavel Sterec was born and raised in Prague’s Jewish community in the wake of the Velvet Revolution and the fall of communist Czechoslovakia. While attending a Jewish high school in the early 2000s, he became increasingly aware of the contradictions between his emerging leftist orientation and the right-wing politics of his community.

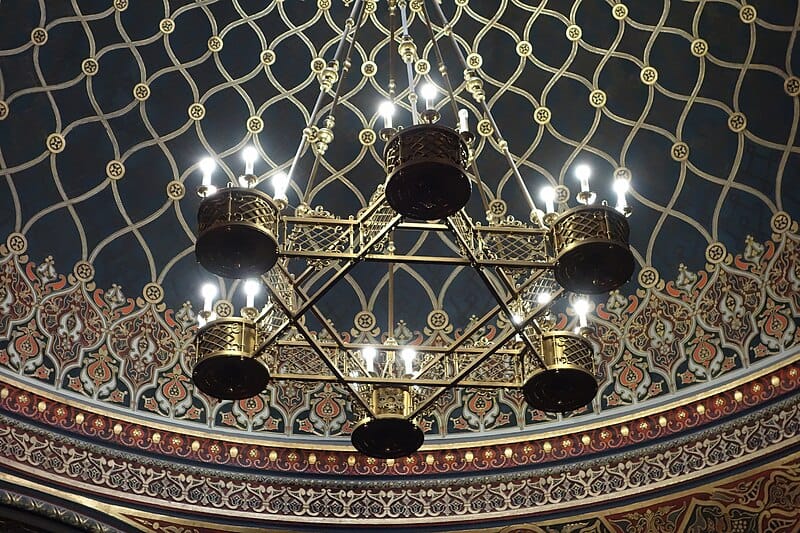

For many, Prague is a marquee Jewish tourist destination, filled with beautiful old synagogues and historic monuments accessible by a single, all-inclusive ticket. But as Sterec explains, the community’s relationship to tourism is part of the problem. “The Jewish museum depends on tourists coming to the Czechia and visiting the Jewish sites, so any controversial content is not welcomed. Local intellectual and religious history that isn’t fit for Israeli and American tourists is basically not presented.”

Disillusioned with a community that flattens the historical diversity of Czech Jewish life and is committed to right-wing alliances, Pavel distanced himself from the mainstream Jewish community altogether.

In 2018, Pavel joined Joe Grim Feinberg, an American researcher at the Czech Academy of Sciences, Einat Adar, an Israeli lecturer at the University of South Bohemia, and others similarly disillusioned with normative Jewish life to form Židovský hlas solidarity – Jewish Voice for Solidarity – in the wake of Israel’s suppression of the Great March of Return in Gaza.

In a state deemed “the voice of Israel in Europe”, this small, Prague-based group is unique and their goals are notably big: to resist an immoral status quo, to be in solidarity with Palestinians, and to herald a new vision of diasporic independence for Jews everywhere.

A complicated alliance

The lands that are now Czechia were once a vibrant center of Jewish art and scholarship, with a population numbering in the hundreds of thousands and roots dating back over a millennium. After the Shoah and multiple waves of emigration to Israel and the West, its Jewish population today stands at around 3,500, only a fraction of its former height. This gives Czechia one of the smallest current Jewish populations in Europe, contrasting France, the UK, Germany, and Russia, which are each home to hundreds of thousands of Jews.

Czechia’s strong connection to Israel dates back to a period before its Jewish population began to wane. In 1918, Czechoslovakia declared independence from a crumbling Austro-Hungarian empire. Its first president, Tomáš Masaryk, was a staunch supporter of the Zionist movement, believing that Czechoslovaks and Jews shared the same aspirations for self-determination. In 1933, he hosted the 18th World Zionist Congress in Prague. Masaryk’s solidarity with the Zionist movement is commemorated today in several sites throughout Israel, including Masaryk Square in Jaffa/Tel Aviv and the Kfar Masaryk kibbutz.

After liberation from Nazi occupation in 1945, the newly reconstituted Czechoslovak Republic provided Israel with crucial training and weapons support during the Nakba. In January 1948, Jan Masaryk, foreign minister and son of former President, signed a covert deal with Haganah representative Ehud Avriel to secure $750,000 worth of infantry firearms for the Zionist paramilitary.

Only one month later, a Soviet-backed coup broke out in Czechoslovakia. The communist regime continued relations with Israel, but targeted the Jews that remained in Czechoslovakia, with synagogues and monuments routinely destroyed, and politicians persecuted in antisemitic show trials. Ties with Israel eventually weakened and were severed completely after the 1967 war as the Eastern Bloc turned to the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

The Velvet Revolution in 1989 and ensuing independence of Czechia saw allegiances change yet again, as anti-communist (and pro-Israel dissidents), including future president Václav Havel, became the political elite in the new state. Havel’s state visit to Israel in April 1990 marked an official end to four decades of Czechoslovak anti-Israel foreign policy under communist rule.

Czechia continues to affirm deep support for Israel today. The first foreign dignitary to pay a visit to Israel after the events of October 7th was Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský. Czechia also routinely votes against UN resolutions calling for an end to the Israeli occupation, including the one presented on 18 September 2024. Pro-Palestine protests, albeit relatively small in number, nevertheless continue to be held in Prague.

Born into exile

Against this backdrop of entrenched Zionism, antisemitism across Czech society, and sparse community, diasporic consciousness has nevertheless endured in the lands of Czechia.

In June 2024, Židovský hlas solidarity gathered to read aloud from multicoloured pages in Prague. Through masks made of flowers, matzah, and keffiyeh fabric, they took turns delivering an important message: the Declaration of Independence of Diaspora.

This most recent in the long series of independence declarations announced in Czech lands was made in the name of “Jews, half-Jews, crypto-Jews, impostor Jews, Jew-curious and barely Jew-ish Jews, as well as Gentiles, and everyone beyond or in between.” It laid out the borders, flags and official languages – or lack thereof – of the independent diaspora:

Our true birthplace was in Exile. Not when one man plotted out land and called it his, not when another built a palace and some elders declared him king, not when his son built a Temple and made it the center of his Land, but when we were kicked out of Eden — it was then that we were born.

It was while wandering the desert, not when carving it up with fences, that we learned to let its flowers bloom.

It was not statehood that made us, but slavery in Egypt, captivity in Babylon, and scattering like seeds across the coasts of imperial Rome.

Drawing inspiration from Israeli visual artist Roee Rosen and his videos for the Buried Alive Manifesto, Pavel sought to embody a “stylization of how these kinds of [official independence] declarations are often read” through the use of colorful costumes, masks, and a menorah sat among flowers. By couching the declaration in parody and performance, the group sought to unsettle its messages from the political narratives and language that they are so entrenched in.

However, what’s at stake here is not just Czechia’s place in the diaspora, but the very linkage between diaspora and homeland itself, and what it means to be independent from this binary.

Forging a Judaism beyond nation-states

“Part of the idea of declaring independence is that you declare [it] from the idea that diaspora is only temporary and is important insofar as it eventually abolishes itself and goes back to where it came from. If diaspora is something independent then it is something that can keep going, or if there's an endpoint to diaspora, then it’s an endpoint that’s in the distant future” Joe, the initiator of the Declaration, tells us.

Joe was born and raised in a small town in Ohio. He did not grow up in a large Jewish community, but rather encountered it later while attending university in the US. There, and in contrast to Pavel’s experience, he became immersed in the secular, left-wing Jewishness common in American academia. When he moved to Czechia, he was immediately exposed to the public Jewishness scaffolded upon anti-communism, oppression by the left, and Israeli nationalism.

Part of what moved him to revolt against this environment was “an impulse to see Jewishness as a way of finding one’s place in the world – where your place is not entirely fixed … If some people are insisting that being Jewish means this kind of right-wing – either liberal, neoliberal, or anti-leftist – symbolism, that it means Israeli nationalism, then, that was all the more motivation for me to be Jewish differently.”

In contrast to Joe, Einat Adar grew up in a religious Zionist family in Israel, although she eventually became involved in Israeli activist circles. She encountered Jewishness in a context so intertwined with right-wing politics that it provoked altogether disillusionment with it as an identity.

After moving to Prague, she continued to engage in demonstrations, lectures, and other dissenting leftist activities within Czechia’s Palestine solidarity movement. It was through these spaces that she first found Židovsky hlas solidarity, and participated in declaring the diaspora’s independence.

To Einat, the notion of diaspora as independent from the homeland-bound condition of exile translates into an active strategy for belonging and political organization, particularly with one’s neighbors.

“The declaration in particular really does make this call for solidarity with other people. We as a group work with other groups in the Czech Republic, obviously, and also Joe sometimes brings in people from different places in Europe. So, in praxis there is always a factor of cooperation just because we are living in diaspora, right? We are not isolated, and so we will always be either close to or even in cooperation with other groups.”

For Židovsky hlas solidarity, then, the Declaration of Independence of the Diaspora was both an inward and outward act – an empowered vision of dispersion beyond exile and a commitment to hybridity, statelessness, and our neighbours. It marks a new chapter in the complex Jewish history of Czechia, and provides a path for Jewish belonging, sovereignty, and organisation across autonomous provinces of diaspora. At the same time, citizenship of diaspora is unrestricted by identity and open to all those who choose to scatter into it:

"WE EXTEND our hand to all the Nations as they prepare to renounce their states, and to all states, if they are willing to forget their Nations."▼

Adam Hinden is an OSINT researcher, soon-to-be anthropology PhD candidate focusing on radical diasporism, and co-organiser of fundraising initiative Totefreedom.

Eliška Vinklerová is a Russian and East European Studies MPhil at the University of Oxford currently researching the Georgian techno music scene as a platform for queer and civic activism.

To donate once or monthly, click here.

Authors

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.