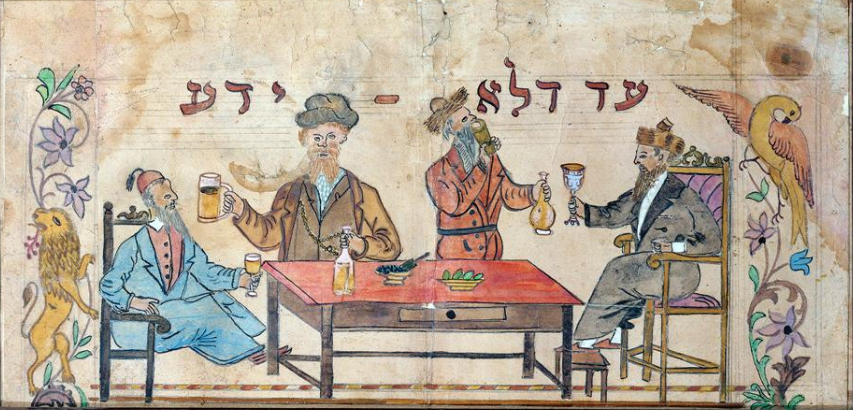

Ask a Jew to explain Purim and without a doubt they’ll mention the commandment to booze. They’ll tell you: we’re meant to get so hammered that we can’t tell the difference between the good guy and the bad guy in the Purim story. It’s the time of year when Hackney residents expect to see Hassidic Jews in Fez hats pissed on an open-top double-decker bus, with klezmer music blaring out of the back.

It’s a novelty. It’s funny. Because, whisper it: Jews don’t really drink. There isn’t a Jewish “culture of drinking.” The ability to drink our weight in pints is not a stereotype the Jews have been blessed with.

And indeed, for many of us in the UK – religious, traditional, or secularised – a pub is a location we first encounter through university or the workplace. A space that, for our parents and grandparents, and for many within our communities, still feels rather unkosher. But Jews do drink, and it’s about more than just whether the spirit is certified kosher or not, or whether the wine’s been handled and bottled by a Jew who keeps Shabbat.

Where else to begin but with the humble Kiddush bottle, the opener of every Shabbat and festive meal. We bless it, take a sip, and pass it around, oldest to youngest. Standing up. Sitting down. In all the possible formations.

It’s cloying. It’s sweet. More syrup than wine. And then it’s blessed again at the end of Shabbat, spilled out on a saucer with a little candle wax, then dabbed on our foreheads and eyes and on the backs of our necks, plus a little on our pockets for prosperity.

There’s Kedem and Manischewitz in the US, made with Concord grapes that have come to define Kiddush wine. And in the UK, there’s Palwin, short for Palestine Wine, around since 1898, which once ran adverts in the Jewish Chronicle with the strapline: “Let your Seder Table help the Jewish colonists by insisting upon Palwin!” According to folklore, the numbers on each bottle correlated to East End bus lines.

Sometimes it’s not actual wine at the Kiddush table but grape juice, which is perfectly fine, because historically an actual red was never a given. In some places, Jews were too poor to purchase grapes, or it wasn’t the right season. In Yemen, they made a drink out of raisins and water, variations of which were called zabib, nabidh and sharab. In Ukraine, they went a step further, soaking the raisins in vodka for the four Passover cups; they named it peisachovka. And in Ethiopia, the Jews went with the grain, brewing a beer of teff and sorghum, known as tella.

Then there’s the synagogue bottle, a flashier cousin of the humble Kiddush wine – usually a hard liquor like arak or whisky brought out for special occasions: a brit milah, a Shabbat chatan, the hakafot on Simchat Torah. It’s dished out in white plastic cups and washes down the driest of foods: sesame Abadi cookies, a handful of crackers, marble cake in a plastic sleeve.

Then there are the bottles that are Jewish beyond pure ritual. There’s mahia – “the water of life” – a drink synonymous with Moroccan Jewry. A brandy of figs spiced with anise, it is a sibling to arak, which is made from grapes, though the names are used interchangeably. And whether fig or grape, it was a tipple beloved by the Moroccan rabbi and Kabbalist the Baba Sali, who’d pour out large cups for his guests. Portrait paintings show him pouring a glass from his miracle bottle, which allegedly never ran out.

Historically, mahia was served by Jews to their Muslim compatriots in makeshift bars, earning the mellah a reputation as a space for the drunk and disorderly, especially among the French colonists. So while in eastern Europe it was “a drunkard is a goy,” in Morocco it was “a Jew without mahia is like a sultan without a beard.”

Although production is no longer exclusively Jewish, mahia brewers in Morocco still stick Hebrew font on the front of their bottles as a sign of heritage and authenticity. And in Israel, the Baba Sali’s face adorns the bottles sold to the hundreds of thousands of mourners who flock to his tomb in Netivot to mark his hillula every January.

In nearby Tunisia, it’s a similar story – one of boukha, a Judeo-Tunisian-Arabic word that means alcohol steam. Another spirit of figs spiced with anise, it is synonymous not only with Jews but a specific Jewish family: the Bokobsas, who’ve been brewing the stuff since 1820.

And it wasn’t just in the Maghreb; across the Muslim world, the Jews did the jobs forbidden to Muslims by Islam. Likewise in eastern Europe, where an estimated 40 per cent of Jews were involved in the production of moonshine or hooch throughout the 1800s. By the 19th century, 85 per cent of all taverns in Poland had Jewish management.

To this list, many more examples of Jewish booze can be added. There’s the much-overlooked etrog liqueur or schnapps, like a limoncello made from Sukkot’s discarded fruit. Given that Jews will pay into the hundreds for a fine-looking specimen, how is the making of the liqueur not de rigueur? And there’s the kosher coffee liqueur, which can often be found in the mishloach manot sent out on Purim, nestled in the basket between a packet of Bissli and the Chocolate Log (or was this only in Stamford Hill?).

And don’t forget the non-alcoholic stimulants: the qat leaves chewed by Yemenite men at the ja’ale – a Shabbat gathering of singing and poetry; and the weed and hash smoked by Jewish teenagers and adults alike in north London and beyond, because, whisper it: Jews like a vice.

So who said Jews don’t have a drinking culture? Let’s pour one out, or light one up, because it’s Purim and we’ve been commanded to do so. Or don’t, if that’s not your thing. Anyway, happy Purim.▼

Leeor Ohayon is a writer from London based in Norwich, where he is studying for a PhD in Creative and Critical Writing at the University of East Anglia.

Author

Leeor Ohayon is a writer of Moroccan and Adeni descent from north-east London.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.