A sandbox for socialism

RIP Zionist summer camp. Hello wild diasporism.

In his 2009 pamphlet Why not socialism?, the Canadian Jewish Marxist philosopher GA Cohen argues that, given the choice, most people would “strongly favor a socialist form of life over feasible alternatives”. He illustrates his point with a camping trip; here, he explains, we wouldn’t dream of charging each other for the nuts we find or the fish we catch. Instead we would relate to each other on grounds of equality and community, sharing our resources and cooperating in our activities. We would be united by the common objective of ensuring that “everybody has a roughly similar opportunity to flourish, and also to relax”, Cohen writes, on condition that they contribute, as far as they can, “to the flourishing and relaxing of others”.

The summer camps I attended with Bnei Akiva – an Orthodox Zionist youth movement with branches in 42 countries – had perhaps something of this: we ate together, shared tents and were hustled through a number of activities, from praying three times a day to the beloved “wide game”, played only on Saturday nights in total darkness. But these camps were also more bound by ideology than Cohen’s imagined camping trip, involving long discussions about whether we were more British or Jewish, and teaching a particular historical narrative on the state of Israel.

Cohen doesn’t deal with the question of what kind of people can afford to go on his camping trip, but a Bnei Akiva summer camp, at today’s rates, costs between £750 and £1,000 (though some camps offer bursaries). The community these summer camps build, then, is restricted by faith and means; the equality they promote comes with significant geopolitical caveats. This wasn’t always the way.

From assimilation to Zionism

In the US, the first Jewish summer camps that emerged in the late 19th century were run by social reformers hoping to offer reprieve to the children of eastern European refugees, many of whom were living in squalid conditions in industrialising cities. Here, the perennial Jewish question – whether nation or religion should be given primacy – received an unambiguous answer: these camps intended to Americanise and thereby assimilate their participants.

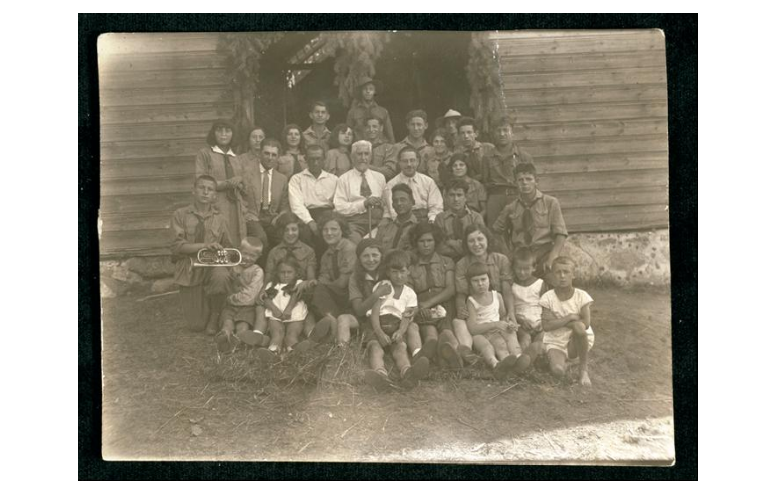

All the way until the 1940s, Jewish summer camps reflected Jews’ ideological heterogeneity: alongside Zionist camps were socialist, Yiddish, communist, anarchist and secular residentials. One history narrates how some socialist summer camps refused to allow children to bring money, asking them instead to share any packages brought from home with others. Such camps valorised all kinds of labour to such an extent that dirty work like cleaning bathrooms was never given as punishment, but considered simply a collective duty.

With the second world war, Jewish summer camps received a new energy and purpose. It became both more of a religious enterprise and more explicitly geared towards promoting the establishment of a Jewish state. Camp Massad, established in 1941, was the first to be run entirely in Hebrew, and brought in a set of Jewish instructors from pre-state Palestine.

British Jewish youth movements have followed a similar trajectory. The oldest, the Jewish Lads Brigade (JLB), founded in 1895, was a means of anglicising Yiddish-speaking eastern European immigrants. It was designed, in the words of its founder – a British colonial army officer who had recently discovered his own Jewish heritage – “to spread among Jewish working lads the habits of smartness and obedience”. In its religious makeup, it was essentially secular; in its politics, it aimed as much at social work as social control. By inculcating discipline, historian Sharman Kadish narrates how the JLB hoped to "protect society from delinquency [and] class conflict", turning working-class and foreign Jewish youth into fit and respectable “Englishmen of the Mosaic persuasion”.

Where the late 1920s and 1930s heralded a major moment in the development of Zionist summer camps in Britain, JLB refused until 1962 to play the Israeli national anthem ‘Hatikvah’ – preferring to sing ‘God Save the Queen’ and religious hymns like ‘Adon Olam’. As the century drew on, however, Jewish youth movements gradually reversed JLB’s mission, bringing Jewish kids together to help them feel more Jewish and Zionist rather than more assimilated.

With the current array of summer camps on offer, it isn’t clear where a generation of leftist Jews on a budget might want to send their children to nurture mutual understanding and collective responsibility. What might it mean to have an alternative, radical Jewish summer camp in the UK today? This summer, two camps are responding to this question in different ways: the new summer camp Beenu, and Our Second Home (OSH).

Wild diasporism

Camp Beenu describes itself as a “wild radical-diasporist” Jewish youth movement, language that has been carefully chosen to distance the camp from Zionism. When I asked one of its founders, Sara Moon, how the idea emerged, she replied that for a long time, there had been “whispers on the Jewish left of starting a youth movement”, and so last year, she gathered a team to make something happen.

Having grown up in the socialist-Zionist youth movement Habonim Dror, Moon describes becoming disenchanted with the movement’s vision of making “socialist aliyah [Jewish emigration to Israel] and living happily ever after” once she encountered clear limits to the kinds of questions she could pose about Israel-Palestine. But believing in the power of youth movements “as the perfect place to build the world we want through education, activism and deep relationship building”, Moon was eager to rework the early Zionist conceptions of collective farming and connection to the land and channel it into a new framework.

She sees Beenu as the beginning of a youth movement of a different stripe, one that cultivates a Jewish identity rooted in the land, a downward orientation that is as much about diasporism as it is climate justice. Beenu will be a site of radical learning; deepening connections to the places we live as a means of climate resilience; and acknowledging the vast heritage of diasporist ideology. The name itself is a way to “uplift the radical Jewish youth movements” of the early 20th century, harking back to Camp Bin (Bee), a popular Yiddish camp that took place in Vilna, Lithuania in the 1930s.

It will be hosted from 18-21 August at Sadeh, a Jewish farm and environmental community centre in Orpington (see our earlier Pickle on Sadeh here), and has a sliding scale of fees to ensure no one is turned away. Sadeh itself is closely tied up with the desires behind the early summer camps: the Jewish Youth Fund purchased the land in the 1940s for a philanthropic Jewish boys’ club, as a place of respite from the difficulties and dangers of life in the East End.

Talia Chain, Sadeh’s founder, described the project to me in reference to doikayt, the Yiddish for “hereness”. It’s a concept that underlies the desire to contribute to the environment in which we find ourselves and a value that was central to the Jewish Bund. In practice, at Sadeh this means planting wheat – and thinking about this both in relationship to the many Jewish laws that use it as one prime example of work (this is why, on Shabbat, we cannot gather and grind, sort or cook), and in relationship to land justice in the UK.

Radical inclusion

OSH, which was founded in 2018 but is now undergoing a rapid process of expansion, holds a similar sense of history, with aims akin to those of earlier youth movements. It is a summer residential for teenage refugees (most aged 16-17), designed to offer a space for them to get outdoors, find their feet and build a community in a new country: all for a £5 optional donation.

It was set up by Amos Schonfield, whose response to the refugee crisis was to draw on his knowledge, gained from years of running summer camps for the Masorti Jewish youth movement Noam. From an initial summer residential for 25, OSH now holds five a year in three locations for young people from 26 countries. Adapting the structure of a Jewish summer camp to a new audience, OSH runs for five or six days at a time, incorporates English language classes, and respects the needs of a group of people who have experienced unimaginable trauma.

Nothing at OSH is compulsory: rather than a set programme, the residential prioritises self-organisation and independence. It does not fix bedtimes out of respect for participants who struggle with sleep, or forbid the use of phones, which could impede participants from taking essential calls from lawyers, but rather lets the group structure their time themselves. This is a decision that Schonfield describes as a move away from “power held for the sake of power”, to an ethos that strives for “a radical inclusion of the marginalised”, culminating in participants learning to lead the camp themselves.

Like Sadeh, Schonfield outlines that OSH builds from Jewish values, with the most important principle gained from his experience in Noam being a fierce belief in youth empowerment and leadership. Once participants go through an 18-month process to become young leaders themselves – via a four-step programme of “participate-train-lead-shape” – Schonfield hopes to bring together young leaders and other volunteers in a va’ad, or council, a space for democratic decision-making about the content and orientation of future residentials.

OSH’s next summer residential runs 24-28 August, and recruitment will soon open for volunteers for the autumn residential in October. The plan going forward is to expand to 10 locations, building further partnerships to spread the model across the UK.

One of the main reasons GA Cohen believed that it feels so difficult to transfer the socialism of the summer camp to society as a whole is that we lack the means to harness existing human generosity: with our “poor social technology”, we feel forced to rely on the market instead. Perhaps one place to start building this technology is the camping trip, and not only as a hypothesis. In dialogue with its Jewish history, Jewish summer camps offer a place not only to test out what it means to cultivate equality and community, but to develop a shared understanding of religion, community, nation, assimilation and refuge.▼

Katie Ebner-Landy is a junior fellow in intellectual history at Harvard’s Society of Fellows, and an editor at Vashti.