A flash of messianic time

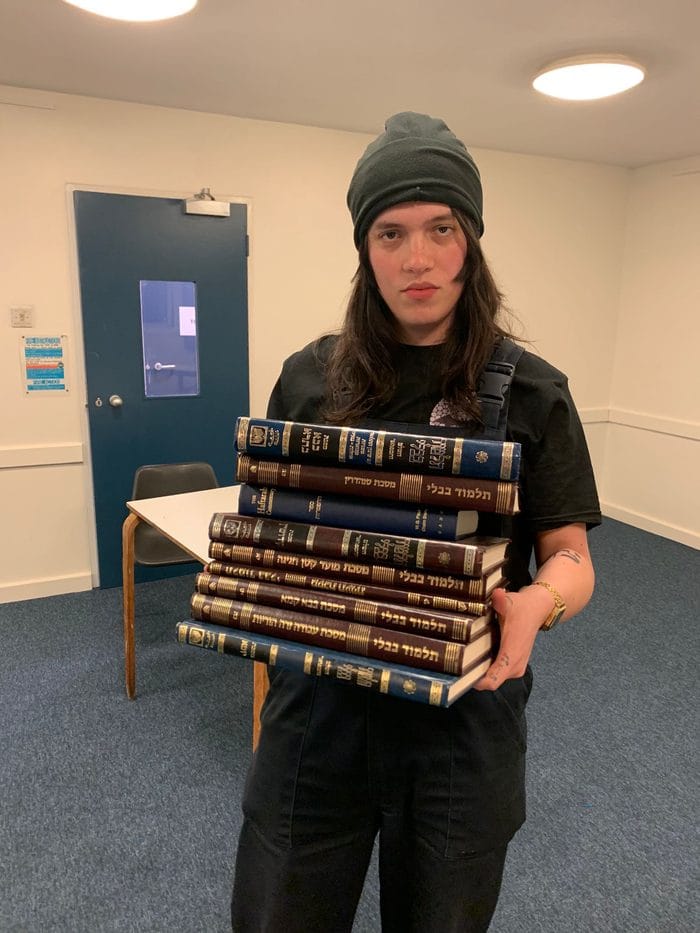

Vashti meets the Queer Yeshiva.

Like many queer and trans Jews, I’ve had a complicated relationship with Judaism. But after years of separation from Jewish life, I found myself feeling the need to return. I attended a Yiddish language course run by Babel’s Blessing, but it was religious life that I missed. So when Babel’s announced they were founding a queer yeshiva, I realised this is what I had needed for a long time: to sit in a circle in a room full of Jewish queers learning Talmud, eating delicious food, arguing and laughing about our place in Jewish tradition and its place in us.

As the 10-week course comes to an end, I am sitting in the cheder of Southwest Essex and Settlement Reform Synagogue with two of the yeshiva’s four teachers, Rabbi Lev Taylor and Hava Carvajal (Joanna Phillips and Rabbi Daniel Lichman are teaching the online sister course over Zoom). After a quick gossip, I started recording.

Naomi Cohen: Explain to me how the project came about.

Lev Taylor: I believe that Talmud has liberatory potential. More than 10 years ago, I heard about this rabbi in Chicago called Benay Lappe who was setting up this queer yeshiva in Chicago. She blew my mind with how she saw Jewish learning, how she saw the Jewish future as something that was created by queers and radicals and weirdos rather than the same old men. Over the last two years, I've been trained up by people in Chicago and now want to bring what they taught me over here.

Hava Carvajal: When I came into my transness, which was a deepening of my queerness, I recognised that at its core was my Jewishness. There seems to be an upsurge of Jewish queers coming back into dialogue with their tradition – I'm one of those people.

LT: A lot of the path has been beaten down in this country as well, especially like through the 80s and 90s, mostly by lesbians – though as far as I know, we in Europe have never had something that says Judaism is queer. So we are building on a legacy – of people like Rabbi Sheila Shulman z"l [zichrona livracha, or “may her memory be for a blessing”] and Rabbi Elli Sarah shlit"a [shetichya leorech yamim tovim amen = “may G-d give her a long and good life”] – and taking it to a new level.

NC: In what ways is this queer yeshiva queer?

HC: As queers, our position against normativity lends itself to a radical rereading of or dialogue with the Talmud.

LT: Yeah, definitely. I would say as well that what makes it queer is not necessarily who's in the space – although obviously everything's queer-led – but our posture, our way of looking at the world through our common experiences of struggle, deviancy and non-normativity. We’re bringing everyone into a way of thinking about our texts as sites of struggle and resistance, into which people can insert themselves.

It's not just that there's something queer about the yeshiva, it's that there's something sacred about being queer. Something about that position – of going against the grain of things – that makes us see the world closer to how G-d sees it: broken but full of beautiful people.

NC: What makes the Talmud specifically the thing to be studying as part of like a queer Jewish educational project? I grew up in Liberal Judaism and before the yeshiva, I hadn’t even really encountered the Talmud. What's going on there?

LT: First of all, why Talmud? The Talmud is a product of a revolution that in late antique Israel, when a group of rabbis, faced with a genocide – the complete destruction of everything they'd known, and an attempt to destroy their story – rebuilt their religion in its entirety in a way that decentred priests, states and kings and recentred ordinary people with extraordinary takes on the world. That is what queers do in every generation.

Because our communities have been so regularly destroyed, and our histories have been so often stolen from us, it is in the nature of queer people that we're constantly rebuilding our community, reimagining what it means to belong, and trying to do that in a way that brings people from the furthest margins into the centre. That's what makes the Talmud queer.

HC: I was having a conversation with a Christian friend of mine and she found it difficult to recognise that the Talmud is not the word of G-d. It’s is not something that bears down on us from above – it's a sea that one swims in. You're surrounded by it, you can be inside and change it. It's not absolute. I think that adds to its queerness.

LT: As to why Liberal Judaism didn't engage with the Talmud, when the Enlightenment happened, modern reforming Jews began to feel that the Talmud was this backwards, Oriental text. In order to get closer to their Protestant neighbours, they focused on Tanach, the Hebrew Bible, especially Prophets, and de-emphasised that stuff that made them look eccentric and different. That’s another reason why it's so important for us to reclaim the Talmud now: taking progressive Judaism to the next stage is not about trying to compromise with bourgeois society but taking tools that are offensive to bourgeois societies and making them our own.

There's a wonderful essay [by feminist scholar Janet Jakobsen] called 'Queers Are Like Jews, Aren't They?' about that position of being on the outside, which is the position of rabbis of the Mishnah and the Talmud and the position the queers occupy. We don't have absolute truth – we have conflict.

NC: What does a Queer Yeshiva session look like?

HC: We have a structure, but we're learning how it fits with the students. We're committed to learning together what radical queer pedagogical pedagogy looks like.

LT: We start by singing. We dedicate our study to people who we're thinking about. We pray. We get in, we look at what we've studied before, we look at the new material. Sometimes we work in chevrutas, in partners, sometimes we all work together. We have big discussions. We do some more praying, we do some more thinking, we dig into dictionaries, but all that stuff I don't think it's what makes a session. I think an essential session is: do people go away feeling more empowered and holier than they did when they arrived? [Caretaker interlude]

HC: Also eating. We eat, we drink, coffee, tea, snacks. It's growing into a very heimish [cozy, familiar] space.

NC: Yeah, it is. I mean, one of the things I don't think you mentioned was that we do this check-in. We share a lot, don't we? I feel like as we've been doing this session people really bring the problems of their week, and we're actually very much there for each other.

LT: To me, that was I think one of the most important bits about what would make it queer. I've done so much Talmud study that has been very competitive and dick-waving – who can get the best words first, who can give the best takes quickest, who's done the most daphim, the most pages. I feel like shifting that round and saying: who could be the most vulnerable? Who can be the most open? You know, it switches it from being a competition into something where we all grow together, where if one person has got one word, that's an accomplishment for everyone.

HC: I do want to say there's nothing wrong with waving your dick around, just in the right context. [Laughs]

LT: I feel like we have to distinguish between queer dick-waving and heteronormative dick-waving. I'm sorry Rivkah, you'll have to cut this! [Editor’s note: she did not.]

HC: It is important that there isn't this separation, because that separation is extremely heteronormative, right? Like, drop all your actual feelings and shit, we're gonna get down to this dry-ass learning. That's not what we're about: what we discuss in the Talmud informs our feeling. [Cake interlude]

LT: You brought us cake! Thank you so much!

HC: [Whispers] Yessss.

NC: I feel like this recording is capturing a lot of what it's like to be in the shul at this time. I hear you are hosting a summer intensive in August. Can you tell us more about that? [Student arrives]

LT: Come on in. We're just doing an interview for Vashti but come and sit.

HC: What can you expect from the summer intensive? Well, you can expect some really great in-depth Talmud learning, really great guest speakers, wonderful atmosphere and vibes.

LT: The goal is to have maybe 100 queers from across this country maybe even Europe come to one place to study Talmud as queers. If we pull it off, it will be fantastic.

We're gonna try and make it as accessible as possible. We've got a venue that's like all wheelchair-accessible and easy to get to from a wheelchair-accessible Tube. We're sorting out child-friendly spaces, and food for people's dietary restrictions. I already know that there's somebody coming who can't have big overhead lights, so we won't have them. I know that I personally often need to take a nap in the middle of the day, so we're building in time for people to take breaks and make sure that if somebody has got to take time out, they will always be able to come back in and understand what's going on.

We’re also trying to think about all different learning styles to make it something that people who have traditionally been excluded from Talmud can feel like this is theirs.

NC: What Jewish education might people need?

HC: Just your aleph-bet.

LT: So it will still be graded. So like, if you come with just your aleph-bet, you will get an experience that holds you where you learn loads more than ever before. But if you come and you've been to yeshiva and stuff like that as well, we're gonna have like, high-level advanced Talmud study. So there will be something here for everyone, whether you are dipping your toe into Judaism for the first time, or for the first time in a long time, or you're an old yeshiva bocher [yeshiva student]. One of the slogans we've always had for Babel's Blessing, the umbrella organisation doing this, is: "If you think you're not Jewish enough, or you think you're not radical enough, you are exactly the kind of person that this is supposed to be for."

We won't get it perfectly right. For me that's also an important principle: not pretending that we can undo years of educational trauma, turn an inaccessible world into an accessible one, or turn a world that hates queer people into a world that loves us. We can't achieve that kind of stuff – but what we can do is try to be open and vulnerable in a conversation where we are all constantly learning how to support each other better.

HC: Perhaps to create a flash of messianic time in the present.

NC: What is the long-term project of the Queer Yeshiva?

LT: I hope we will have weekly Talmud sessions going forward. I hope that by next year, we'll be able to do the same summer intensive somewhere beautiful and rural and countryside-y, where people can switch off their phones because they won't have signal anyway and just enjoy being by a lake or a mountain. I hope that like in 10 years' time, people will still be studying Talmud as queers.

I hope above all else that the future is completely unrecognisable and that people will come in and usurp us and say that we are no longer doing it right, because that will be an indication that we've created enough space for people to make change.

Naomi Cohen is a contributor to Vashti.