Six million and one

‘By my death I wish to make the strongest possible protest against the passivity with which the world is permitting the extermination of the Jewish people.’

The following speech was delivered by David Rosenberg at a Holocaust Memorial Day event hosted by Na’amod: British Jews Against Occupation on 27 January 2024.

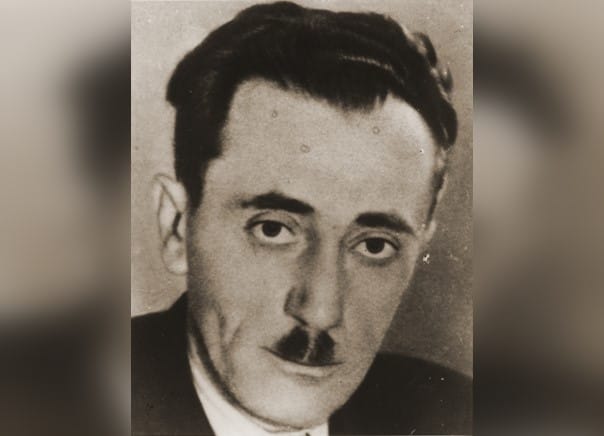

It’s impossible to do justice to millions of personal tragedies, so I want to tell you mainly the story of one person, Szmul Zygielbojm: a Polish Jewish socialist, anti-fascist, internationalist and ardent anti-Zionist. His sudden death in London in May 1943, was intimately entwined with the destruction of Jews in Warsaw. So to me that makes six million and one.

You won’t have read about him in the Jewish Chronicle, or heard him praised by our Chief Rabbi or even Rachel Riley. A factory worker from the age of 10, he slept on park benches in his teens, was a trade union organiser in his 30s, and a prominent Bundist Jewish socialist in his early 40s, when the Nazis invaded Poland.

When the Nazis announced the first steps towards ghettoising Warsaw’s Jews in November 1939, Zygielbojm told a mass gathering: “Don’t go voluntarily to the ghetto. Don’t lose courage. Remain in your homes until you are removed by force.” This act of defiance put a target on his back.

Fearing for his life, his comrades hid him, obtained false travel papers, then smuggled him out of Poland in January 1940 with a mission: to tell those with power in the West what was happening under Nazi occupation, and persuade them to take extraordinary actions to save the Jews. He gave detailed reports in Belgium, France and many cities in America. In March 1942, he was invited to represent the Bund on the Polish Government-in-Exile in London.

Here, he received news about the ongoing genocide through underground channels and relayed it to politicians, diplomats and the press. He wrote articles and spoke on BBC Radio. In September 1942, he told a mass Labour party meeting about the Nazis’ first use of poison gas for mass killing, at Chelmno, where 40,000 Jews plus some Roma were murdered in seven weeks. At that time, he believed 700,000 Jews had already been slaughtered by the Nazis at killing centres.

In late 1942, Jan Karski, a non-Jewish Polish underground resister, personally passed him a message from Bundists in the Warsaw ghetto, imploring Zygielbojm to ask Jewish leaders in London to chain themselves to the gates of parliament for a hunger strike until death unless Britain acted. Zygielbojm told Karski they would never do that, but promised to do all he could.

By early April 1943, he had exhausted almost every channel. In a letter then, to his brother Fayvel who left Poland before the war, he wrote: “I am almost at the end of my tether. According to the latest news that reached me this week, 300,000 Jews are still alive in Poland [out of more than 3 million before the war] but the slaughter continues … Here people are making beautiful speeches to promote their party politics. The Zionists are using the Jewish martyrdom as part of their fundraising campaign for Palestine.”

‘My life belongs to the Jewish people in Poland and, therefore, I give it to them’

Two momentous events began on 19 April. In the Warsaw ghetto, hundreds of Bundists, communists and left-wing Zionists launched an incredible uprising in a united body, using smuggled and improvised weapons. Meanwhile in Bermuda, British and American diplomats opened 11 days of talks about the situation in Poland. But the talks concluded offering next to nothing practical for any possible Jewish refugees, and on 10 May, Zygielbojm received news that the ghetto uprising had been crushed.

The following day, he wrote a series of letters, then took an overdose of sodium amytal. His letters explained that his suicide was an act of protest against the Allied powers whose indifference and failure to act permitted the extermination of Poland’s Jews.

We can all hear the echoes of that today.

Zygielbojm continued: “The responsibility … falls, in the first instance, on the perpetrators but indirectly it also burdens … the peoples and governments who have made no effort … to put a stop to this crime.

“I cannot remain silent. I cannot live while the remnants of the Jewish people, whose representative I am, are being exterminated. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto perished with their weapons in their hands in their last heroic battle. It was not my destiny to die as they did, together with them. But I belong to them and in their mass graves.

“By my death I wish to make the strongest possible protest against the passivity with which the world is permitting the extermination of the Jewish people … My life belongs to the Jewish people in Poland and, therefore, I give it to them. I wish that the surviving remnants … could live to see, with the Polish population, the liberation that it could know in Poland, in a world of freedom and in the justice of socialism.”

‘We fought for dignity and freedom, not territory nor a national identity’

Zygielbojm’s story is discomfiting for a British state that took in so few refugees before the war, failed to act on credible information during the war, and admitted such small numbers of Holocaust survivors after the war.

It should embarrass Britain’s Jewish establishment too, which made no effort to memorialise Zygielbojm. It needed a grassroots action in the 1990s by a committee of Bundist survivors in London who had known Zygielbojm personally, and younger Jewish socialists (myself included), to achieve a memorial plaque unveiled in 1996, with members of Zygielbojm’s surviving family flying in to be present. He did not know it, but one of his three children, Yossel, survived as a Red Army partisan.

Yossel read about his father’s death in circumstances that are poignant tonight given our panel. Yossel wrote to me in 1994 about his partisan group liberating the city of Gorny Vakuf in Bosnia from the Nazis. In the Nazi headquarters he found a German newspaper, dated 21 May 1943, that carried a mocking article about his father’s suicide. “The televised accounts of bloody fighting in Bosnia bring back those terrible memories,” Yossel added.

In educational work, the Bundists on our committee – such as Esther, who survived Auschwitz; Wlodka, who survived the Warsaw ghetto (and is still alive today); and Majer – always stressed the range of Holocaust victims, especially the Roma, who they said, “died in the same ways as the Jews for the same reasons”. These Bundists insisted on drawing universal lessons from the khurbn, the destruction: to combat all racism, welcome all refugees and create a world based on respect for everyone’s human rights.

Zygielbojm’s young comrade in Warsaw, Marek Edelman, second in command of the ghetto uprising, who died in Poland in 2009, retained his socialist, anti-Zionist and anti-fascist politics until he died. In his 70s he took part in a convoy taking aid to Bosnia.

Edelman openly challenged the lies of Israeli politicians, who dishonestly tried to weave together the Warsaw ghetto resistance with the war to establish Israel. “We fought for dignity and freedom,” Edelman reminded them, “not for territory, nor for a national identity”.

I want to finish with the words of a left-wing Israeli, no longer alive, called Boaz Evron. In 1983 in the wake of Israel’s trail of destruction in Lebanon so reminiscent of Gaza today, he wrote of “two tragedies” that happened to the Jewish people in the 20th century: “the Holocaust – and the lessons drawn from it”, especially by Israel’s leaders and many Israelis.

He described “a strange moral blindness where the world is always conceived as a hater and persecutor where Israelis consider themselves free of all moral obligation in their relation to it … free to contract agreements with the world’s most oppressive regimes, to negotiate arms deals with the worst governments, and to oppress non-Jews subject to their rule”.

Here tonight, we are showing the opposite: our desire to liberate both Palestinians and Jews from that reactionary nationalist mindset, to build a world of equality and dignity for all.▼

David Rosenberg is an educator, writer and tour guide of walks of London’s radical history. He has been a co-organiser of educational trips to Auschwitz for trade unionists and anti-racist activists. He teaches an adult education course on the Warsaw ghetto uprising. He is on the editorial collective of Jewish Socialist magazine.