Below is an edited version of Vashti’s weekly newsletter, The Pickle. To get The Pickle every Thursday, subscribe.

With leading UK politicians keen to cosy up to the Jewish community, while at the same time going out of their way to attack “foreign workers” for Britain’s socio-economic woes, it’s important to remember that not so long ago working-class immigrant Jews were treated as “aliens” in Britain – and neither British politicians nor Anglo-Jewry’s self-appointed leadership sided with them. Instead, it has been up to radical Jews to make the case against the hostile environment, long before it ever earned that name.

In this week’s Pickle – the second in our three-part series on labour organising – Michael Richmond and Alex Charnley offer a timely reminder of how working-class Jews joined forces with other immigrants and radicals in London’s East End to confront rising xenophobia at the turn of the century. One clear lesson? We shouldn’t trust the Anglo-Jewish establishment, which has historically functioned to promote British state interests within Jewish communities, to defend those who are marginalised, Jewish or otherwise▼

Eli Machover

The loom of racism

by Michael Richmond and Alex Charnley

The late British Sri Lankan novelist and activist Ambalavaner Sivanandan once called immigration controls the “loom” of British racism. The catchphrase “immigration concerns” has also allowed for subtler racist manoeuvring in the centre and distortions of anti-racist history on the left. British centrist “anti-racists” today have successfully instrumentalised their professed love of Jews to attack socialists while supporting immigration controls at every step. The instrumentalisation of anti-semitism within the Labour party prompted an absurd counter-argument from the left: that the Labour party, and by extension the British left, is “proudly anti-racist”. Nothing could be further from the truth.

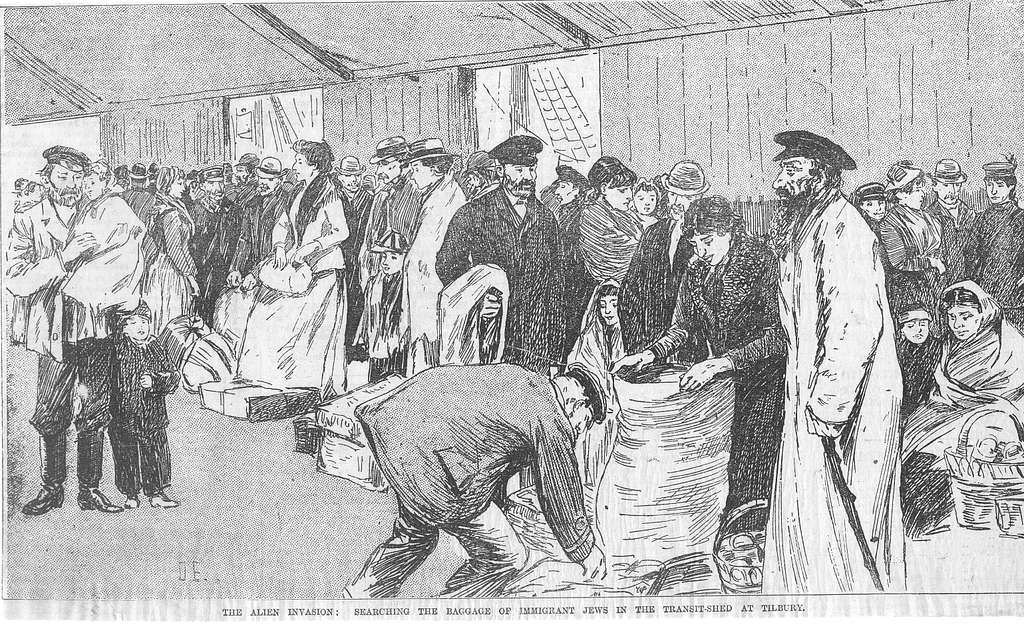

The Aliens Act of 1905 forces us to think more concretely about how racism changes and new forms are established on the basis of new relations of production. Britain’s first modern immigration controls, the act was passed by Arthur James Balfour’s Conservative government and implemented by the succeeding Liberals, the other main party until Labour replaced it in the 1920s. The act submitted Britain’s working-class Jewish population to the threat of deportation – though neither Jews nor any racial minority were named in the law itself. Legal scholar Nadine El-Enany has shown how Britain imitated measures taken by its white settler colonies in Canada, Australia and Southern Africa, where early immigration laws took on the appearance of “race-neutrality” while producing “racialised effects”.

The anti-semitic left

It wasn’t just conservatives who supported immigration controls. Beatrice Webb, the driving force behind the Fabian Society, a forerunner to the Labour party, echoed the sentiments of many in Britain’s workers’ movement when she claimed that Jews had “neither the desire nor the capacity for labour combination [ie unionising]”. Anti-semitism extended to the most militant leftists: in 1891, two leaders of the great dock strike, Ben Tillett and Tom Mann, sent letters to the London Evening News calling for controls against Jews. Another hero of that strike, John Burns, demanded: “England was for the English!” Bruce Glasier was one of the founders of the Independent labour party (ILP), along with Keir Hardie and future Labour prime minister Ramsey MacDonald. He later took over from Hardie as editor of ILP journal Labour Leader, writing of Jewish immigration: “[N]either the principle of the brotherhood of man nor the principle of social equality implies that brother nations or brother men may crowd upon us in such numbers as to abuse our customs.”

What the scholar Satnam Virdee calls “socialist nationalism” crystallised during this period. As the labour market nationalised, so did labour. British socialist nationalists were willing to work with, and demand violence from, the bourgeois state to police both foreign and British-born proletarian Jews. They agitated for “alien control”, in part to regulate the more radical, internationalist elements of the working class, as did communal leaders in the assimilated Jewish community. Practically all consistent resistance to immigration controls was led by Jews, ostracised from a Jewish community divided across class lines. Yiddish-language anarchist paper, Der Arbeter Fraynd (“The Worker’s Friend”), printed out of the Berner Street Club at the heart of the Radical Jewish East End, castigated British workers for their nationalism and Jews for religious conformity: “[F]rom the pure socialist viewpoint […] We may say again that no colonisation, no land of one’s own and no independent Government will help the Jewish nation. Jewish happiness will come with the happiness of all unhappy workers, and Jewish emancipation must come with the general emancipation of humanity.”

Practically all consistent resistance to immigration controls was led by Jews, ostracised from a Jewish community divided across class lines.

The organised Jewish left

Newly arrived Jews in Britain around the turn of the century had to struggle on multiple fronts, pushing back against super-exploitation by employers, the racism of trade unions and the cynical paternalism of the settled Jewish elite. Most couldn’t speak English so ended up working for other Jews as apprentices. Such precarious conditions of low pay and isolation made existence extremely hard and resistance even more so. And yet this period saw the flourishing of a diverse and experimental radical Jewish scene. In a manner not dissimilar to the grassroots labour, housing and migrant rights organising being done today by groups such as Acorn and IWGB, working-class Jews set up their own unions, strikes and protests, as well as an Alien Defence League based in Brick Lane to counter anti-immigrant racism.

Newly arrived Jews in Britain around the turn of the century had to struggle on multiple fronts, pushing back against super-exploitation by employers, the racism of trade unions and the cynical paternalism of the settled Jewish elite.

Jewish socialists were up against racism from wider society and from within the British left. Over the 1890s and 1900s, Jewish members of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), later the British Socialist party – people like Theodore Rothstein, Zelda Kahan and Joe Fineberg – held the party leadership to account for its anti-semitism and militarism, eventually achieving leadership positions themselves but facing racism for their trouble.

When the Trade Union Congress supported immigration controls in 1895, a London meeting was organised by ten Jewish trade unions; prominent Jewish leftists Eleanor Marx (youngest daughter of Karl) and Peter Kropotkin spoke. A leaflet promoting the event announced:

Jews! The English anti-semites have come to the point where the English workers’ organisation calls on the government to close England’s doors to the poor alien, that is, in the main, to the Jew. You must no longer keep silent. You must come in your thousands to the meeting in the Great Assembly Hall.

In 1895, Joseph Finn, a Jewish worker in Leeds, wrote a pamphlet A Voice From the Aliens, chastising English workers:

Surely we cannot blame the foreign working man, who is as much a victim of the industrial system as is the English working man. Neither can we blame the machine which displaces human labour. The only party at fault is the English working class itself, which has the power, but neither the sense nor courage, to make the machines serve and benefit the whole nation, instead of leaving them as a source of profit for one class […] In Germany the immigration is one-tenth of the emigration. In the United States it is vice versa. Still, the wages of a tailor in Germany is 15s, whilst in the United States it is 58s. What will our opponents say to this? If the English worker has reason to be dissatisfied with his lot, let him not blame his foreign fellow working man; let him rather study the social and labour question – he will then find out where the shoe pinches.

Finn already saw the need for workers in Europe to find an answer to capital’s outsourcing of production to sites overseas with access to cheaper labour power:

Whether, so far from being the enemies of the English workers, it is not rather the capitalist class (which is constantly engaged in taking trade abroad, in opening factories in China, Japan, and other countries) who is the enemy, and whether it is not rather their duty to combine against the common enemy than fight against us whose interests are identical with theirs.

While many socialists today cannot, 19th-century “alien voices” could differentiate the free movement of capital from the subordination of the global working class to this movement. A tiny minority of leftwing organisations took up anti-racist positions. William Morris (also known for his textile designs) and Eleanor Marx left the SDF to create the Socialist League, pursuing a more pluralist, internationalist socialism composed of a mixture of anarchists and Marxists in a handful of cities. They opposed the SDF’s chauvinism. Eleanor Marx, in an 1884 letter to Wilhelm Liebknicht, bemoaned the fact that “whereas we wish to make this a really international movement, [SDF leader Henry] Hyndman whenever he could do with impunity, has endeavoured to set English workmen against foreigners”.

The league’s founding manifesto, written by Morris in 1885, included a pointed passage that would have been anathema to Hyndman:

The Socialist League therefore aims at the realisation of complete Revolutionary Socialism, and well knows that this can never happen in any one country without the help of the workers of all civilisation. For us neither geographical boundaries, political history, race, nor creed makes rivals or enemies; for us there are no nations, but only varied masses of workers and friends, whose mutual sympathies are checked or perverted by groups of masters and fleecers whose interest it is to stir up rivalries and hatreds between the dwellers in different lands.

Solidarity that stretched to Jews was rare compared to nationalist currents coursing through the left at that time. As Virdee puts it: “[S]uch politics proved incapable of generating the vocabulary required to hold the line against the rising tide of an aggressive, racialising nationalism to be found throughout society, including much of the working class.”

Communal gatekeepers

Nor could Jewish workers rely on Anglo-Jewish elites, who were keen to disassociate themselves from newer, poorer Jews. The representative organ of the community, the Board of Deputies, was formed in 1760; the Board of Guardians, which issued charitable poor relief, in 1859. They were led by wealthier, more integrated Jews, descended from much earlier migrations. To protect their own positions and civil rights, they wouldn’t allow anyone to cast aspersions on their allegiance to the nation.

The Anglo-Jewish establishment recognised working-class Jewish activism early on, and the dangers it posed. They circled on Jewish radicals, trying to control Jewish labour. Sir Samuel Montagu, Jewish Liberal MP for Whitechapel, believed socialists posed the greatest threat to British Jewry. A constant thorn in their side, Montagu sponsored conservative trade unionism, conciliated disputes between Jewish employers and workers, and convinced printers not to publish radical materials. Conservative Anglo-Jewish MPs like Harry Simon Samuel and Harry Marks spoke at rallies of the proto-fascist, extraparliamentary pressure group the British Brothers’ League; Jewish businessman and Tory politician Sir Benjamin Cohen campaigned and voted for the Aliens Act; he was made a baronet shortly afterwards. The editorial position of the Jewish Chronicle, established in 1841, wavered between pleas for Jewish integration and support for restriction and repatriation of Britain’s Ostjuden (eastern European Jews).

Communal leaders and organisations even took it upon themselves to arrange for proletarian Jews to leave for America or return to eastern European pogroms. Communal philanthropic organisations, serving a quasi-state function, rationed and withheld aid to destitute immigrant Jews. Operating through bourgeois relations of conditionality and moral improvement, charities encouraged recipients to ditch the Yiddish language. Such internalisation of British state interests for social control by appointed (or self-appointed) leaders of stratified “communities” is characteristic of longue durée British race and class management in its colonies and on British soil right up to today. The shaping of identities by state appointment erases the class antagonisms that have always existed within racialised communities, providing the racist common sense of sameness and alienness the far right weaponises.

Communal leaders and organisations even took it upon themselves to arrange for proletarian Jews to leave for America or return to eastern European pogroms.

No borders, no nations

As well as being labour history, these historical scenes help to temper some of the media sycophancy around the diversity of the Tory front bench. The election of Britain’s first PM of colour changes nothing about Britain’s racial regime and in fact underlines one of its more longstanding features. Sunak, Patel and Braverman, children of immigrants, have nothing in common with the people they subject to unimaginable suffering in detention camps, in the southeast of England and elsewhere. They have no problem differentiating their own family stories of “legal” migration and respectable settlement from the proletarianised “illegal” migrants they propagate against. From the beginning, border controls deepened racial divides, as well as ethnic, class and generational divides within racialised groups. This is how the British state managed to recruit from the racialised in the Edwardian era of aliens, throughout the neoliberal transition and how it still does.

As for Starmer, Sivanandan’s famous quip rings in the ears. “What Enoch Powell says today, the Conservative party says tomorrow, and the Labour party legislates on the day after.” Respectable British journalists are dismayed by the Powellite rhetoric of Braverman, but not the precedent of immigration detention, which they have long supported. The modern system of nationalised border controls is no more than 150 years old and has been resisted by global working-class movements and radicals every step of the way. Sivanandan was writing of the British late seventies and early eighties when he wrote: “The loom of British racism had been perfected, the pattern set. The strands of resistance were meshed taut against the frame.” We need to revisit this metaphor.▼

Michael Richmond was a co-editor of the Occupied Times and Base Publication. He has written for publications including OpenDemocracy, New Socialist and Protocols.

Alex Charnley was illustrator and co-editor of the Occupied Times and Base Publication.

Their book, ‘Fractured: Race, Class, Gender and the Hatred of Identity Politics‘, is out now with Pluto Press.

Authors

Alex Charnley was illustrator and co-editor of the Occupied Times and Base Publication.

Michael Richmond is the co-author, with Alex Charnley, of the book Fractured: Race, Class, Gender and the Hatred of Identity Politics, out now with Pluto Press.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.