Why are anticolonial academics being accused of antisemitism?

Because we’ve uncoupled antisemitism from the coloniality of race – something Israel’s advocates are only too pleased about.

In Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Frantz Fanon – the great anticolonial freedom fighter, psychiatrist and philosopher – wrote of the Black condition under colonialism:

For not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man. Some critics will take it on themselves to remind us that this proposition has a converse. I say that this is false. The black man has no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man.

His description reminds me of how I feel to be Jewish in the Global North in today’s post-Holocaust, post-Nakba world. It is not that Jews (particularly white, western Jews), like colonised Africans, are denied permission to independently define themselves. Rather, just as the white man needs the Black man to define himself, so must the Jew be someone for others.

I had this feeling recently when I received an email from a team of editors in Germany – postcolonial and decolonial scholars – for whom I had agreed to adapt my talk ‘White supremacy, white innocence and inequality in Australia’. The email requested that I remove two lines from my text: one which referred to Israel “running the longest occupation of any people by another in the world”; the other that cited the state’s “regime of racial supremacy over Black and Brown Jews”. In the context of deepening attacks on critics of Israel, including Jews and Israelis, from German cultural, academic and municipal institutions, I categorically refused.

The context of these assertions was a discussion of how I moved from being Jewish in Ireland to being a Jew in Israel/Palestine, and how that affected my relationship to whiteness. In positioning myself in relation to Israel’s racial regime, I was declaring that, as a white European Jew with Israeli citizenship, and a migrant-settler on the occupied Gadigal lands known as Sydney, Australia, I am not innocent. My subjection to antisemitism does not cancel out the privileges that accrue to me via the other axes of my identity. The editorial team eventually conceded this, having been forced to reassess their automatic discomfort with my Jewish anticolonialism. Their discomfort made me aware of our dwindling ability as anti-Zionist Jews to define how we experience racism, as well as of how our Jewishness can be used to legitimate it.

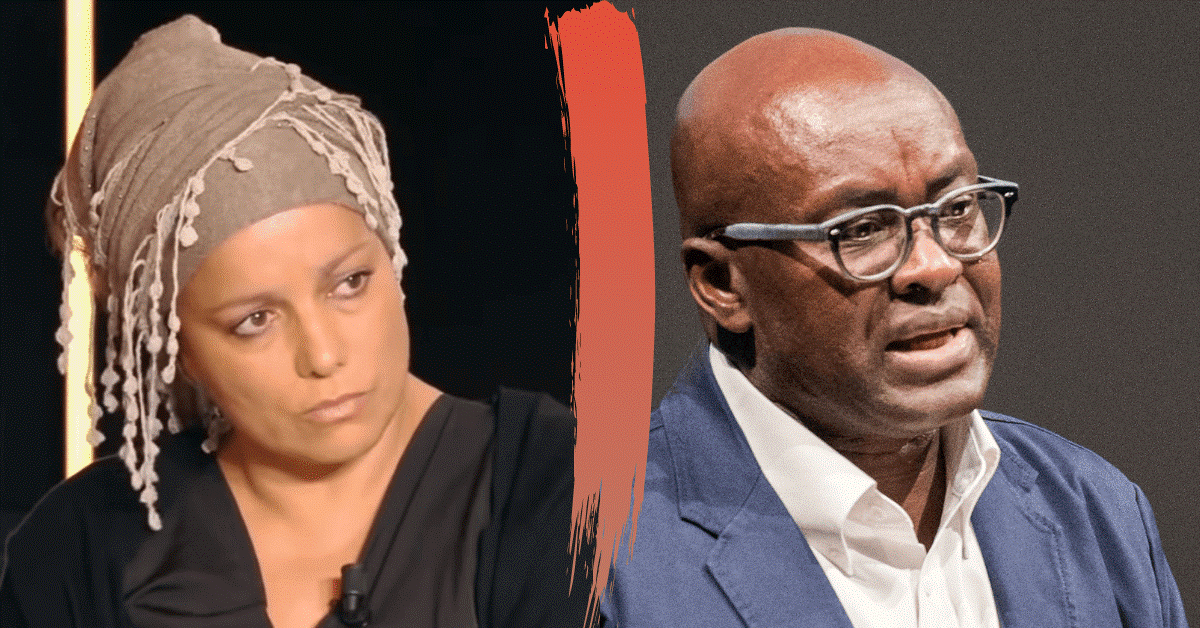

The responsibility to address one’s complicity with racism and colonialism is also the point of a recent article by the French-Algerian decolonial activist Houria Bouteldja, for which she is currently facing a public campaign of defamation on trumped-up charges of antisemitism. Bouteldja wrote about the antisemitism directed towards April Benayoum, a French beauty queen recently crowned Miss Provence, whose father is from Israel.

In Bouteldja’s article – originally published on the left-of-centre news site Mediapart, though taken down in response to public outcry and now hosted on the website of the French Union of Jews for Peace (UJFP), a telling fact in itself – Bouteldja denounced the antisemitic attacks on Benayoum in no uncertain terms. However, she also used the case to distinguish between antisemitism and criticism of Israel, which had been amalgamated in most accounts of the attacks. As Bouteldja remarks in her article, the confused “anti-Jewishness” among some Twitter users, which combines a very French antisemitism with an anticolonial impulse, is an unfortunately unsurprising reflex, given the Zionist movement’s efforts to inextricably tie Jewishness to Israel. Inviting Miss Provence to take a position against the state, rather than her Israeli origins necessitating she defend it, Bouteldja wrote:

[O]ne can be the daughter of an Israeli and position oneself against the colonial reality of Israel. One cannot be Israeli innocently [Here Bouteldja paraphrases the great anticolonial writer and leader Aimé Césaire, who wrote: “No one colonises innocently, and no one can colonise without impunity”]. However, by making the choice to stand with the anticolonial struggle, [Benayoum] can be sure that the decolonial movement would welcome her with open arms.

Here, Bouteldja rejects a Zionist discourse that sees only one possible fate for Jews: to be inexorably tied to a racist, colonial state that occupies another people in our name, even as we deny or even attempt to dismantle it. To be an anticolonial Jew is anathema, not only to the communal gatekeepers who stand steadfast with the racial colony of Israel, but to those gentiles who use our tragedy to exculpate their own continuing complicity with racism and colonialism at home and abroad. This binding of Jewishness to Israel works antisemitically to deny Jews the capacity to defy this destiny – to have, as Fanon might put it, any “ontological resistance”.

But in insisting on the non-innocence of Miss Provence, Houria Bouteldja also accuses herself, arguing that the fight against racism must be multi-directional and introspective. In an article written after her cancellation, she reminded us that in her book Whites, Jews, and Us, she too declared culpability:

[N]o French person is innocent, starting with me…. Not only am I not innocent – because I am French – but I am also a criminal. Therefore, I allowed myself to judge Miss Provence not innocent because I had already conducted my own trial and had already been served my sentence … My crime rests on one tangible fact: the share of imperialist revenues between the Western ruling classes and the white, and to a lesser extent non-white, working classes.

Yet this materialist conception of race, that emphasises its structural nature and its exploitative effects, does not register with those who hear racism only in one key: the moral one. This moralistic antiracism focuses on the attitudes of individuals detached from the structures that produce them. This dominant understanding of racism couches it in terms of personal wrongdoing, of unsavoury and outdated attitudes, refusing to see race as bound up with colonialism such as that of the Zionist state. Only in this moral conception is it possible to conflate anti-Zionism – a form of opposition to colonial domination – with antisemitism – a form of racism which, like all racisms, is inextricable from colonialism. Responding to accusations of antisemitism using the language of morality therefore runs the risk of being unable to disentangle antisemitism and anti-Zionism and thus can compound the anti-materialist view of racism, rather than unsettling it.

This is what happened to the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, around whom controversy erupted last spring when a right-wing German politician accused him of relativising the Holocaust. The criticisms focused on Mbembe’s 2016 essay, ‘The Society of Enmity’. In it, he draws comparisons between apartheid South Africa and both the Israeli occupation and the Shoah; though he heavily qualifies this latter comparison, saying it took place “in an extreme fashion and within a quite different setting.” Yet merely placing apartheid and the Shoah side-by-side – never does Mbembe equate them – was enough for him to be accused of antisemitism.

In a recent interview that touched on these accusations, Mbembe chose a language of moral outrage: “The idea that I might harbour hatred and prejudice against any other human being, or any constituted state as such, is totally repugnant.” The impulse to respond in this way, even to people who cynically and selectively deploy antiracism, is understandable; of course where we stand on racial injustice is bound up with our personal morality. However, the cases of both Bouteldja and Mbembe illuminate the fact that appeals to morals have little effect on those who view antisemitism and its epitome, the Shoah, as purely moral matters, decoupled from the coloniality of race. Bouteldja illustrates the hypocrisy that this moralistic elevation of antisemitism leads to: so many of those outraged by the April Benayoum affair have remained silent as the French journalist Rokhaya Diallo has been repeatedly subject to anti-Black attacks from French media.

Race works both in specific ways and as a generic logic of domination, elevating some over others, splintering solidarities in the service of white supremacy. As I write in Why Race Still Matters (2020), the elevation of antisemitism as the racism above all racisms, and the contention that any discussion of the Shoah alongside other genocides renders it banal, constrains solidarity between Jews and other racialised people, thwarting a fuller understanding of race as a colonial mechanism and a technology of power for the maintenance of white supremacy. Attacking Bouteldja and Mbembe displaces antisemitism, but does nothing to fight it.

In fact, any response to accusations of racism which uses the accuser’s terms is unlikely to penetrate, regardless of what claims it makes to righteousness or trauma. Instead, in the interests of really addressing antisemitism, we need to talk to others who experience racism and to those with a shared commitment to defeating it in all its forms. For white Jews, such as myself, we must also recognise the ways in which we benefit from racial whiteness under white supremacy while working against antisemitism as a key part of the racist apparatus that is not detachable from other racisms. As Houria Bouteldja writes: “When I stop seeing myself as innocent, it is me who is saved.” Claiming our non-innocence does not cancel out the wrong that has been and continues to be done to us. Understanding this is essential for Jewish anticolonialists seeking to define antisemitism on our own terms. ▼

Alana Lentin is Associate Professor of Cultural and Social Analysis at Western Sydney University. Her latest book is Why Race Still Matters.

Author

Alana Lentin is Associate Professor of Cultural and Social Analysis at Western Sydney University. Her latest book is 'Why Race Still Matters'.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.