‘I am the saddest, angriest, most disappointed Jew in the world’

An interview with Holocaust survivor Marione Ingram.

7 October saw the “worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust”.

Over the past seven months, this framing of 7 October has time and time again crossed the pages of the legacy media. It’s a framing that has been repeatedly voiced by Joe Biden – be it during his first visit to Israel following the attacks, while commemorating the five year anniversary of the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, or on Holocaust Memorial Day itself. Likewise, David Cameron used his own Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) address to say: “After the horrors of 7 October, we must renew our vow – never again. That is our solemn duty – today, tomorrow and always.”

These framings amount to more than a numerical exercise. When Israeli delegates to the United Nations affixed yellow stars emblazoned with the words “Never Again” to their chests during a meeting of the Security Council in late October, the intended message was clear: those who refuse Israel “the right to defend itself” are guilty of countenancing a second Holocaust.

This is Holocaust revisionism, pure and simple. Jews in Israel today are not facing mass industrial slaughter as European Jews did at the hands of Nazism. Those who dive down this rabbit hole wind up tying themselves in knots with staggering conclusions that are downright offensive to most Jews – such as when the darling of the pro-Israel commentariat and war correspondent cosplayer Douglas Murray penned an article for the Jewish Chronicle in which he argued that Hamas was actually worse than the Nazis.

The use of public Holocaust memory by Israel is not new. Historian Gabriel Winant writes that the state of Israel uses the phrase “Never again” as “a machine for the conversion of grief into power”. Mourning and statehood have become so intertwined that daring to conceive of Jewish safety beyond the bounds and borders of ethno-nationalism leaves one vulnerable to the charge of having failed to learn the Holocaust’s central lesson.

Zygmunt Bauman, a sociologist and Holocaust survivor, first warned about the “privatisation” of the Holocaust “as a private experience of Jews, as a matter between the Jews and their haters” some forty years ago.

This is the mistake made by thinkers like novelist Harold Jacobson, who argues that it is unconscionable, as if by definition, to accuse some Jews, somewhere, of the very crime that once killed them in their millions. And we saw this logic in action when Kate Osamor, the MP for Edmonton, was suspended from the Labour Party for listing Gaza among ‘recent genocides’ in an HMD message – despite the HMD Trust itself describing the annual fixture as an opportunity to remember not just the millions of Jews and other groups murdered during the Holocaust, but also those killed in subsequent genocides.

The privatisation of the Holocaust risks us misunderstanding the ongoing catastrophe in Gaza, too, as the private experience of Palestinians, a matter between the Palestinians and their haters in Benjamin Netanyahu’s war cabinet. Most liberal media commentators only go as far as arguing for Netanyahu’s dismissal, as if all “trouble” in Palestine-Israel would evaporate upon his departure. That there may be a relationship between the legacy of the Holocaust and the horrors in Gaza remains largely unsayable in many quarters, though some understanding of their link is implied by the rallying cry of Jewish groups protesting in solidarity with Palestinians: “Not in our name”.

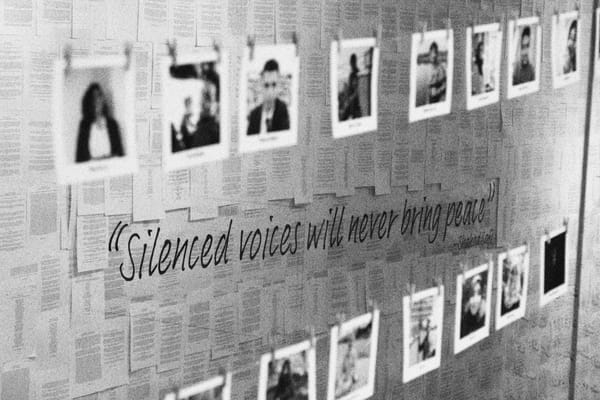

Marione Ingram, an 88-year-old German-American Holocaust survivor, is one such person who has been routinely marginalised for saying that “Never again” is right now in Gaza. Everyday since Israel’s military action began, she and her husband, Daniel, have protested outside the White House in Washington DC, calling for a ceasefire. In January, Marione’s scheduled speaking tour in her native Hamburg was abruptly “postponed” amid a wider German clampdown on pro-Palestinian activism.

As Marione herself acknowledges, many Jews take exception, even grave offence, to her position. Perhaps most controversial are the parallels she draws between her own experience of being a child in Hamburg during the Holocaust and the experiences of Palestinians living under near-relentless Israeli bombardment in the present. One can dispute the historical precision of such a comparison, but as I listened to her speak, what came to mind was one of the final lines of Masha Gessen’s New Yorker essay, In the Shadow of the Holocaust: “Comparison is the way we know the world”.

Of course, we can also apply that framing when trying to understand why so many Jews have drawn comparisons between the Holocaust and the events of 7 October. This way of knowing the world styles itself as comparison but is ultimately little more than equivalence; it is a way of knowing which smooths over the history of violent persecution, ethnonationalism and occupation that contextualises the Hamas attacks, to instead view what happened in Israel that day as representing an existential threat to Jews everywhere.

The next, perhaps more urgent question, one that lingered in my mind in the days following my interview with Marione, is how we might make comparisons in order to know the world in ways that are not so dangerous, that do not lead us to seek justifications for atrocity or stay silent in its face.

The following interview was conducted on 10 March 2024, and has been edited for length and clarity.

Levi: Your speaking tour in Germany was cancelled earlier this year because of your vocal opposition to Israel’s assault on Gaza. I wanted to ask you about this in relation to Holocaust memory more largely. I think we can see a version of Holocaust memory playing out in a very dangerous way in Germany, where a kind of “Holocaust guilt” means criticism of Israel is smeared as antisemitic, and even Holocaust survivors such as yourself get caught up in that.

Marione: That’s true, and I think in part [it is because] they are not making the distinction between Jews and the Israeli government’s actions vis-a-vis Palestinians. As a Holocaust survivor I went through exactly what the children in Gaza are going through. I went through it with bombings by the Brits and the Allies – it was called Operation Gomorrah; the target was the civilian section of Hamburg, not the port or the infrastructure but the civilian section. Because I’m a Jew, my mother and I were not allowed to get into bomb shelters and were even thrown out of a church. The bombing was ten days and ten nights, so the result of this ten day and ten night bombing was the streets were littered with burnt corpses. It was the worst bombing in the European war.

And on top of that, the Holocaust. So I have experienced exactly what the children in Gaza are experiencing. I’m not a historian – it is just my experience that motivates me to be a peace activist, that motivates me to speak out against war. I am against all wars. But the irony for me as a militant pacifist is that the [second world] war and this horrific bombing which killed between 40–80,000 people in a four-hour period, saved my life, and saved the life of my mother and my sisters because we were able to go into hiding. We were hiding during the rest of the war from the summer of ’43 to May ’45, when the war ended.

I’m really interested in that – how your experience of the Holocaust has shaped your attitude toward persecution and injustice.

There’s an irony in that as well, because almost all of the people who have been “cancelled” – almost every one of the people censored is a Jew. Jews are very, very active in this fight against Israel. My activism and my fight for justice and inclusion dates back to my childhood. I celebrated my eighth birthday in an earthen dugout where we were hiding, in a little sort of raised ditch, overgrown with hazelnut bushes. Without food, of course without presents, without anything that makes life bearable. I said to my mother that if I lived, if I survived the war, I want to become a peacemaker.

Nowadays, the Holocaust has become something bordering on the sacred, that you cannot take its name in vain, somehow, but you can use it as an excuse to make a war, as Netanyahu is doing right now. As a Holocaust survivor, and as someone who lost all of my relatives, I resent this “holification” – I know that there’s no word like that – of the Holocaust. The Holocaust was the most horrific event of the 20th century. What happened on 7 October was a horrific and horrible attack. It was not a Holocaust. It did not happen in a vacuum. It was the result of 70 years of dispossession, 17 years of virtual imprisonment – people unable to move about freely. But if you want to use the Holocaust, I would suggest – and I think I will be roundly criticised by Jews, by Germany, maybe by America – I would consider what Israel is doing in Gaza as a holocaust, of a different kind. It is a genocide. It is obvious to me that Israel wants Palestinians out of Gaza, out of the West Bank. Already they are putting land that doesn’t belong to them on sale. I am, as a Jew, horrified that Jews are doing this – you are Jewish?

I am, yes.

– because I think that we of all people should know better and should act better. And probably that is naive on my part, but how I feel. I am angry and resentful that Jewish people are doing this to their neighbours. And what is being done is what was done in Germany – Jews were dispossessed of their properties. My grandmother and grandfather were removed from their gorgeous apartment and forced to move into a different section of Hamburg. And this is what Israel has done. Jews in 1930 who belonged to various professional guilds were banned from these guilds. It is, to me, as though Netanyahu is using the playbook of American racism and German Holocaust beginnings. I think that Hamas and Netanyahu are one and the same; they are both to be condemned, and this war has to be stopped. I am too old to go to Gaza, unfortunately, because if I was even twenty years younger I would go there and try to be physically helpful. I have been an activist since the beginning of my life, when I came to America and was immediately aware of America’s racism. I became a civil rights activist, I have been an anti-war protestor, I have been arrested numerous times for peace and against injustice. Excuse me, I’m just seeing an absolutely gorgeous hawk flying outside my window. I think that might be a sign.

I want to go back to two things that you said. The first is about the Holocaust being treated as something sacrosanct, not only as the exclusive property of Jews but of Zionist Jews.

Yes. I’m not a Zionist. After the war, I wanted to go to Palestine. A Zionist group rounded up children from across Europe. Many of the children were orphans – they had seen their relatives murdered in front of their eyes. We were rounded up and all of us were in a series of three villages on the River Elbe [in Germany]. Zionists were our teachers. For the first time we had enough to eat, for the first time we were treated with affection and respect. So I wanted to go to Palestine, where all of the other children were being smuggled to. There was a conference and the discussion was my going to Palestine, when one of the people said to me – and mind you I was probably 11 or 12 – that Israel needed intelligent young women like me to produce sons. And that was such a shock to my very young system because I thought they wanted us to go to Palestine to make a country where we would be safe, but not a country where I was going to be a baby-maker. So I declined and I didn’t go. I have since been in Israel but only a visitor to my [former] classmates, all of whom are Holocaust survivors. I was appalled at the walls, at the humiliation Palestinians had to go through just to move about. One of my former classmates and friends, who lives in one of Israel’s oldest kibbutzim, showed me what Palestinians had to go through. And he, as an Israeli, as someone who has fought in all of the initial wars, was saddened by what Israel was doing.

I think that Israel has lost an opportunity to make that entire area a real haven for Jews. That now is destroyed. I don’t think Israelis will ever again be able to feel safe as a result of what their government has done to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. Israel might be able to eliminate this current Hamas, but they will create a bigger opposition, an opposition that will be harder, meaner, and more determined. I have a friend, Kamir, in Gaza, who first lost his wife while she was delivering a newborn baby. Killed by a bomb, both the newborn baby and his wife. A short while later, his remaining daughter was hit by a bomb. Kamir, who has been a lifelong peacenik, conveyed that he now wants to fight.

I am not a fighter, I abhor violence, but I do understand that if you kill my beloved wife and my beloved children, I think it would be difficult to continue fighting for peace. I think the lust for revenge in many people will be greater than ever. I want a place where Jews are safe. Netanyahu and his government have made it impossible for Jews to feel safe. I fear for Israel, I fear for us as Jews that we will never have a place where we are safe. We have not tried to make a safe place for Palestinians. I don’t think they are going to want to make a place safe for us anymore.

You’ve drawn this parallel between what is happening in Gaza at the moment and your own experience of the Holocaust. But something that I think many Zionist Jews find offensive about sections of the pro-Palestinian discourse is that the actions of the Israeli government get compared to Nazism, or Israelis get compared to Nazis.

I have not been present when Israel’s actions have been called Nazi-like, but I have compared – and I did it today with you – the oppression of Jews before the Holocaust to the oppression Palestinians have faced in the last 70 years, since the Nakba. The Israeli government are not Nazis, but they are in the same league as people who oppress others. Kissinger was a Jew and the greatest warmonger America ever had – he threatened to bomb Cambodia back into the stone-age. And he was glorified for years before he finally kicked the bucket. He was the most objectionable warmonger, along with Dick Cheney. The Israeli government and its army aren’t Nazis, but they are behaving like all oppressors and people who make wars. So I don’t think they should be too offended if their actions are likened to those of the Nazis.

I think it to some extent ties back to what we were talking about earlier. The Holocaust has become this sacrosanct thing, the paragon of all evil – so to make any comparison to it is seen, through that framing, as a trivialisation of the Holocaust, as a kind of Holocaust denial. But even on Holocaust Memorial Day, when we say “Never again” repeatedly – what that actually means if you’re not allowed to make connections between events is lost on me. What do you think of the phrase “Never again” and what that means in the present?

“Never again” is a hollow phrase because [humanity has] done nothing but [similar things] again and again and again. Nothing has been learned from the Holocaust. I think that there have been more holocausts of different natures. I think that the Holocaust was a unique event but since then there have been so many unique events. They are not the Holocaust but they are actions against human beings that are unacceptable. Hitler and Germany wanted to rid the world of Jews. Israel wants to rid that area of Palestinians. I don’t know what to call that, and I’ll leave it to you to put a name to it – but I think the Holocaust shouldn’t be made holy. It should be made an example.

I am the saddest, the angriest, the most disappointed Jew in the world, I think. I’ve experienced exclusion, bombs, the loss of family, hunger, starvation. To me it is the most horrific negation of “Never again”, what Israel is doing in Gaza today as we speak. Netanyahu and his ilk say that October 7 was like the Holocaust. What does he call 31,000 dead people? What is that, if 1200 people was a Holocaust? It is a bitter pill, a very bitter pill.▼

Levi Cohen is a writer from London.