Why is the Jewish Chronicle whitewashing Britain's antisemitic history?

Vernon Bogdanor’s recent op-ed is consistent with the paper’s long history of placating the British establishment, even in its anti-Jewish prejudice.

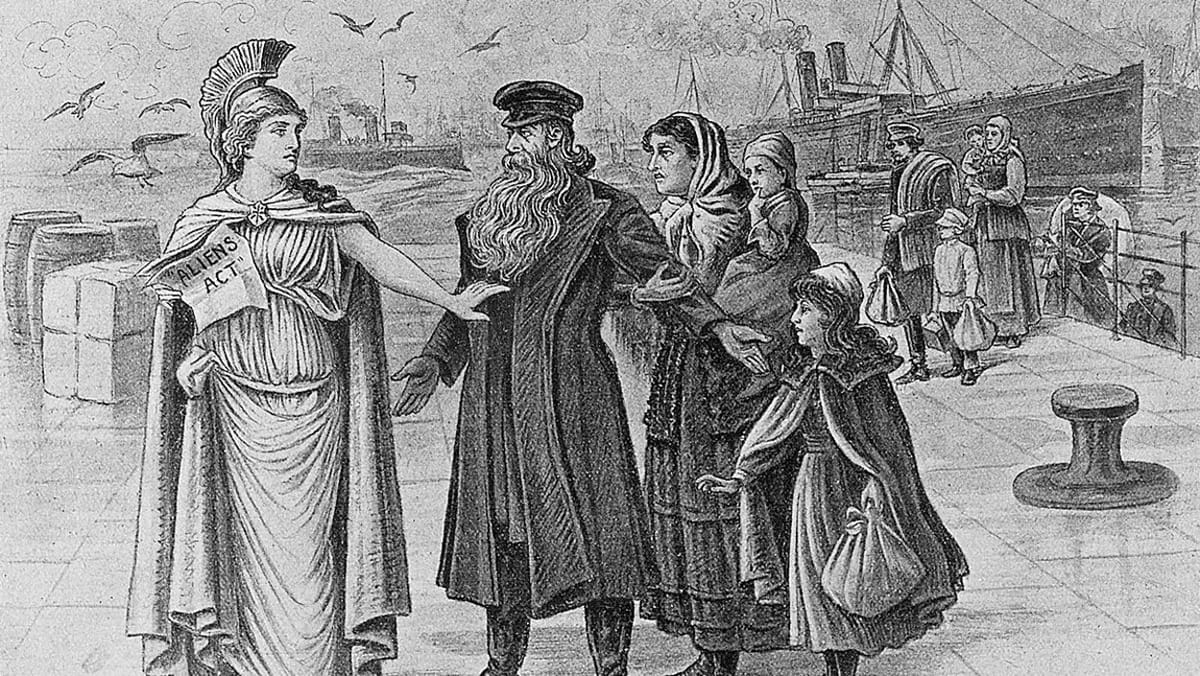

The Aliens Act of 1905 is generally remembered as a shameful example of antisemitism perpetrated by the British state. Its architects, prime minister Arthur Balfour and Conservative MP William Evans-Gordon, explicitly intended the legislation to limit the number of Jews who could enter the country at a time when they faced extreme persecution in the Russian Empire. Historians have viewed the legislation as a precursor not only to Britain’s racist immigration acts of the 1960s and beyond, but also to Britain’s failure in the 1930s to offer refuge to millions of Jews fleeing Nazi Europe.

In a recent article for the Jewish Chronicle, constitutional scholar Vernon Bogdanor attempts to overturn the established view. Praised by the Chronicle’s editor Stephen Pollard for his “fascinating reassessment”, Bogdanor argues that the bigoted motivations and discriminatory effects of the act have been overstated. Constructing this argument required Bogdanor to omit important context.

Professor Bogdanor emphasises the Aliens Act’s provision for those seeking asylum but ignores the origin and impact of these provisions. He is right that the act was far more generous about providing asylum than subsequent immigration legislation. Yet this generosity was not freely given. In truth, the act’s main champions actively resisted the inclusion of asylum provisions, arguing that they would be exploited. Balfour only relented once it became clear that the act could not be passed without enshrining the right to asylum, as demanded by the Liberal opposition.

Despite the asylum amendments, the Aliens Act was still a retrograde step. For two centuries prior to its introduction, those fleeing persecution had been allowed to enter and remain in the UK with zero questions asked. The new legislation obliged asylum seekers to prove they were being persecuted, which many of those fleeing Tsarist oppression struggled to do; someone fleeing their village because of a nearby pogrom would rarely have concrete proof.

The limited asylum provisions that the act did make were essentially nullified just nine years later by the Aliens Restriction Act of 1914. If the act had any legacy, it was not in providing asylum rights, but in establishing criteria in British law for the exclusion of “undesirable immigrants”.

Bogdanor presents the act’s advocates as sympathetic to the plight of asylum-seeking European Jews, yet the quotes he brandishes amount to little more than the usual throat-clearing with which politicians preface their arguments for excluding refugees. He refers to Evans-Gordon’s British Brothers’ League as “an organisation […] to pursue the cause” of immigration control, failing to mention how the league is more often described: as the UK’s first proto-fascist movement. The league trafficked in xenophobic and racist rhetoric, warning that England would become “the dumping ground of the scum of Europe” and referring to Jewish immigrants as “sewage” to be disinfected; they organised large and intimidating rallies, often near Jewish areas of the East End, with placards declaring “Britain for the British” (the similarities to Mosley’s British Union of Fascists that came to prominence a few decades later are clear). From the limited information Bogdanor presents, one might be forgiven for thinking of Balfour only as a noble defender of Jews. He fails to mention Balfour’s lamenting of the “miseries” that “hostile” Jews had “created for Western civilisation”, or his implication that Jews could never be truly British (not to mention his views on Black people).

Lest Balfour’s views be excused as a product of their time, it is worth recalling that there was broad opposition to the act, from supporters of the Conservative party to numerous Liberals – such as Winston Churchill, then a young Liberal MP – to the Jewish Chronicle itself under two different editors. At the time, the Chronicle described the act as “retrograde and un-English”, an “act of retrogression” that “alone would suffice to make” the year in which it was passed “a year of note in the far-flung eons of Jewish history” , and “an inhuman monstrosity not worthy of existence”.

Given this, one might wonder why the Chronicle decided to publish Bogdanor’s shoddy revisionism. One reason is that the paper has historically been motivated, at least partly, by a desire to propitiate the British establishment. This may explain why it spread fears among Jews already established in Britain that Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe would ruin the respectability they had worked so hard to build. Perhaps that same sentiment motivates the downplaying of the British state’s antisemitic history today.

Another factor is the Chronicle’s long-running attempt to popularise the idea that anti-Zionism is synonymous with antisemitism; the complicated history of how antisemitism and Zionism have actually related to one another is, of course, inconvenient to this endeavour. These complications come to the fore in a figure like Balfour, best-known for his eponymous 1917 Declaration on the one hand, the Aliens Act on the other.

One solution to this quandary is to brazenly ignore or deny all inconvenient facts, as JC editor Stephen Pollard has proved perfectly happy to do; take his full-throated defence of Polish politician Michał Kamiński, whose antisemitic statements and past associations would provide more than enough material to earn him condemnation were Kamiński a critic, rather than an ally, of the Israeli state. It is the same attitude that leads Bogdanor to end his article with a swipe at former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, whom he has previously described as representing a “much greater” threat to Jews than the far right, arguing that a Corbyn government would “spread the lesson that Jews are not quite like other citizens”. Ironically, this claim is much truer of Balfour. Yet in the warped world of today’s Jewish Chronicle, it is those like Corbyn who are smeared and those like Balfour who are whitewashed. ▼

Daniel Lewis is currently completing a degree in Philosophy and German at the University of Leeds.