Happy Yom Kippur!

Vashti revisits the Yom Kippur Ball.

A notice appears in a Yiddish newspaper, or pasted to a lamppost, or in a shop window. It’s handed out at a meeting of the anarchist Pioneers of Liberty, or outside shul on Shabbos morning. There will be mixed dancing. There will be a lukewarm buffet. There will be no God, comrades!

It’s 1888, or 1905, or 1927. We’re in London, or New York, or Chicago, or Montreal, or Warsaw, or Chelm. The event is being organised by the Gruppe Proletariat, or the Independent Socialists, or the manager of a Jewish deli who doesn’t see why he should miss out on the sales and publicity that would result from staying open on the most mournful day of the Jewish year.

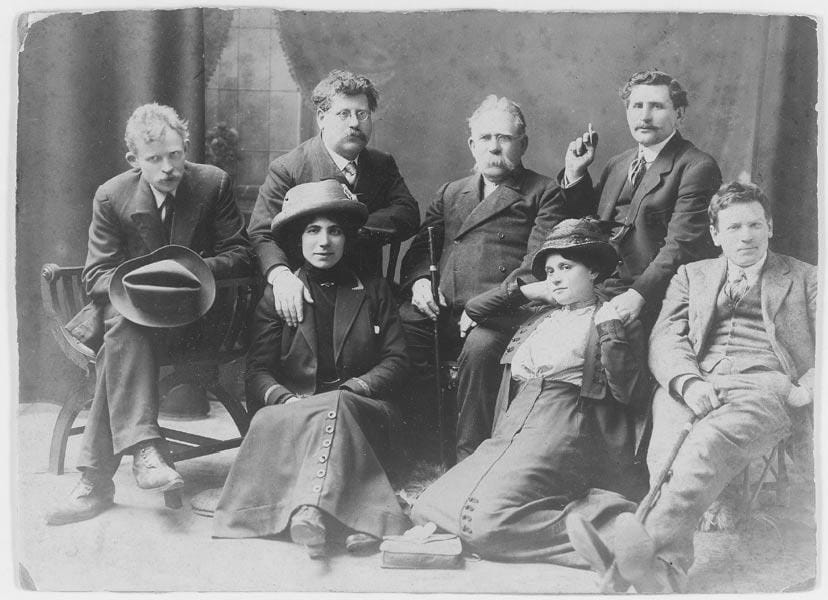

From the 1880s to the 1920s, the Yom Kippur Ball was an integral part of leftist Jewish life in Europe and North America. Starting in the East End then migrating westward, Jewish anarchists and atheists turned a sombre day into a riotous party filled with food, music and anti-religious speeches. The first ball (that we know of) was held in London in 1888. There Benjamin Feigenbaum,an editor of the radical Yiddish newspaper Arbeter Fraynd (Worker’s Friend), gave an hour-long speech in which he asked ‘Is there a God?’, challenging the almighty “to kill me on the spot so that he may prove his existence.” When this failed to occur, Feigenbaum announced the start of the inaugural Yom Kippur Ball.

To the ball-goers, religion was the opiate of the masses; they recognised no God, nor indeed any master. They looked at their fellow Jewish workers who shuttled between dank sweatshops and rat-infested rooms, then at the bosses and landlords they sat next to in shul, and decided that religion was hypocrisy. If capitalists were not atoning for their sins on Yom Kippur, why should the Jewish worker observe? Why should they fast, when hunger was part of their daily life?

It’s interesting to look at how other Jews reacted to the Yom Kippur Ball. Were they appalled? Intrigued? Amused? They certainly weren’t always impressed. In September 1883, the New York Times reported that the police (unsuccessfully) attempted to prevent “Hebrew Anarchists” from throwing a Yom Kippur Ball, after the previous year’s event invited “strong protest […] by orthodox and liberal Jews in this city against this profanation of their great fast by the unbelievers”.

Documentary paucity makes it difficult to work out exactly how long the tradition lived, or why it seemed to have mostly died out by the late 1920s. Jewish assimilation, and increasing state repression of anarchists, likely played a part. Perhaps the balls continued, but smaller, and the press lost interest. Perhaps the Jewish left felt that they had made their point.

Fast forward a century or thereabouts, and I’m in east London, meeting with fellow Jewdas members about a party we’re planning on 8 October, three days before Yom Kippur and four days after the anniversary of Cable Street.

“The venue isn’t sure about the name.”.

“Oh?”

“Yeah, they said the council won’t grant an events license for ‘Geoffrey Cohen’s Fascist-Smashing New Year’.”

“How about ‘Fascism-Smashing New Year’? Surely it’s okay to smash the concept?” Everyone was reasonably happy with this – who says anarchists can’t compromise?

“Great. I’ve ordered the ‘Happy Birthday! There Is No God’ banner, and twenty Ken Livingstone masks.”

“Celebrate all the sins you are glad you committed,” we type into the Facebook event description. “Dress like you hope the messiah never comes.”

The contradiction of the Yom Kippur Ball is that it is at once decidedly anti-Jewish and profoundly Jewish. “You had to be a Jew to avail yourself of a blintz given out by a Jewish organisation on Yom Kippur,” writes Eddy Portnoy in his Tablet article on the Yom Kippur Ball. “Otherwise, it just wasn’t heresy.”

If I’ve learned anything from my involvement in Jewdas over the last five years, it’s this: reinventing tradition is Jewish tradition. Unorthodox Jews have always known this: training as Kohenot, joining queer daf yomi group chats, writing alternative Haggadot, opening Yiddish pay-what-you-can cafés. We find each other, and find ways to keep our Jewishness alive in ways that mean something to us.

Over 200 people came to the our 2016 Yom Kippur Ball, to partake of bands, beigels and bountiful boxed wine. There was a “sin raffle”, in which guests were invited to submit the best sins they had committed the previous year; winners included “left a sausage roll wrapper in the JSoc kitchen” and “adultery… TWICE!” A bunch of drunken punks, we danced to the socialist classic ‘Daloy Politsey’ (Down with the Police), linking arms and lifting people up on chairs.

Unlike the Yom Kippur balls of the 1880s, there were no protesters beating down our door. No fascists turned up to be smashed; nobody even took to social media after the event to inform us that we were shaming our parents.

The lack of backlash was both a relief and a disappointment. We didn’t want violence or arrests, but we had hoped to draw more attention to the resurgence of fascism in the UK, and to spur members of our community to take a stand against it.

Member’s of IRN-JU who organised aYom Kippur Ball in Glasgow last year reported a similar response. Their 75-strong event was billed as “a rowdy but respectful dinner theatre, with 4 different acts of comedy, poetry, and music, all by queer Jews”. Contrary to expectations, “the reaction was overwhelmingly positive,” according to Misha and Joe of Pink Peacock. “We had one negative reaction [from] an anonymous anarchist Jew in Scotland who felt that we were being anti-religious and excluding frum comrades […]. But the point of the ball is to give non-religious Jews a place to go on Yom Kippur. The wider Jewish community in Scotland either didn’t hear about us, or didn’t care.”

The Yom Kippur Ball has lost its power to shock. Why?

One reason is scale. The balls of 1890s New York or 1920s Poland drew thousands of attendees; ours, dozens. But even if our simchas had been bigger, it’s still hard to imagine angry mobs would’ve turned up. Has the Jewish establishment decided to embrace anarchism? Or have its sacred cows simply changed?

Of all the things I’ve done with Jewdas, the most contentious was an act of religious observance: a seder. For the most part, the event was unremarkable: we read the Haggadah, sang the usual songs and ate a kosher l’Pesach vegan dinner. Yet we invited the ire of the Daily Mail, the Board of Deputies and several MPs, thanks to the attendance of one particular guest: the erstwhile Leader of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, Jeremy Corbyn MP.

A bunch of left-wing Jews noshing bacon on Yom Kippur is no longer seen as a threat. But a bunch of left-wing Jews dining with a politician who supports Palestinian liberation? An existential threat to Jewish life. Then Board of Deputies President Jonathan Arkush called us “a source of virulent antisemitism” (maybe he was offended we didn’t invite him). Former Labour MP Angela Smith tweeted: “Corbyn’s attendance at the Jewdas seber [sic] reads as a blatant dismissal of the case made for tackling anti-Semitism in Labour.”

The thing that brought Jewdas media attention and communal condemnation was not blasphemy, but anti-Zionism.

“Maybe to reflect changes in the Jewish establishment,” one Jewdas organiser suggested, “our banner should not read ‘THERE IS NO GOD’, but ‘WE DON’T BELIEVE IN THE STATE OF ISRAEL’.”

In the nineteenth century, Jewishness was defined by religion; today it’s defined by nationalism. The politics of anarchist Jews have not changed much in the past 200 years: we are and have always been heretical and antinationalist. The difference is that now, the second part scares people more than the first. ▼

Hannah Gold is a writer, youth worker, and community organiser with Jewdas. She lives in a queer Jewish house share in London with her son.